When we think of an old-style computer terminal, it has a CRT screen: either one of the big 1970s VDUs with integrated keyboard, or maybe one from a later decade with more svelte styling. You would have found other displays in use in previous decades though, and one of them came our way that we think it worthy of sharing.

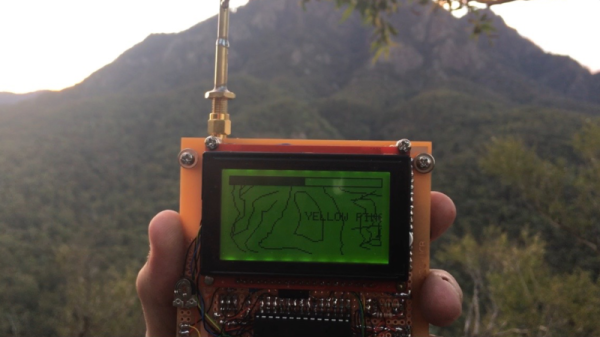

[Dan Julio] was given several tubes of Siemens DL1416B 4-digit 17-segment LED displays by a friend, and decided to use them as an unusual retro display for his terminal project. These devices are an alphanumeric display with a parallel interface that can show a subset of the ASCII character set as well as a cursor. He had 213 of them, so made plans for a 64 character by 16 line display, however on discovering a quantity of the parts were non-functional he had to scale back to 12 lines of 48 characters.

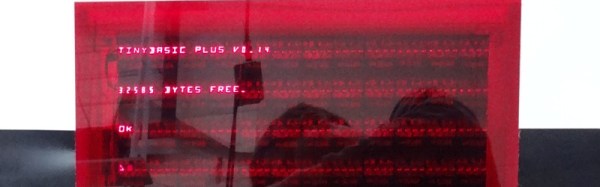

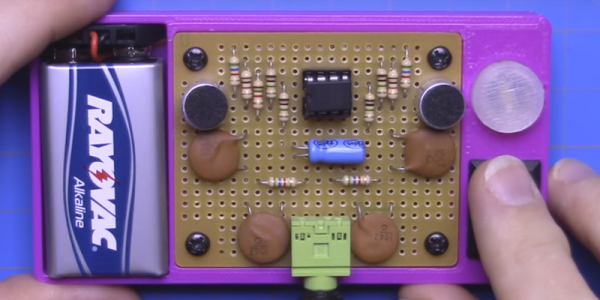

The displays are mounted on PCBs in groups of four, controlled by a PIC16F1459 and some shift registers. These boards are then daisy-chained via a TTL serial line. The whole display shares one of the three serial ports on a Teensy 3.1 with his retro keyboard that has its own PIC controller, the others serving a serial printer port and the terminal serial port. The Teensy software has two modes: serial terminal or a Tiny Basic interpreter, and the relevant repositories are linked from the project page.

Since each set of DL1416Bs takes 250 mA, the whole display consumes about 9 A at 5 volts. On top of that the keyboard uses another 500 mA, so a sufficiently powerful supply had to be incorporated. This is mounted along with the Teensy in a very well-made enclosure, and the whole is mounted on what looks like a surplus monitor stand for a very professional finish.

To take us through the terminal’s features he’s posted a YouTube video that we’ve placed below the break. It comes across as a surprisingly usable machine, as he logs into a Raspberry Pi and edits a file, and takes us through some features of the BASIC interpreter.