In the summer of 1987, the Atari magazine ST-Log caried a piece entitled “Atari Sets Off Fireworks!”, a profile of the use of Atari computers in professional firework displays by Astro Pyrotechnics, a now-defunct California company. Antic podcast host [Kevin Savetz] tracked down the fireworks expert interviewed in 1987, [Robert Veline], and secured not only an interview, but a priceless trove of photographs and software. These he has put online, allowing us a fascinating glimpse into the formative years of computerized pyrotechnics.

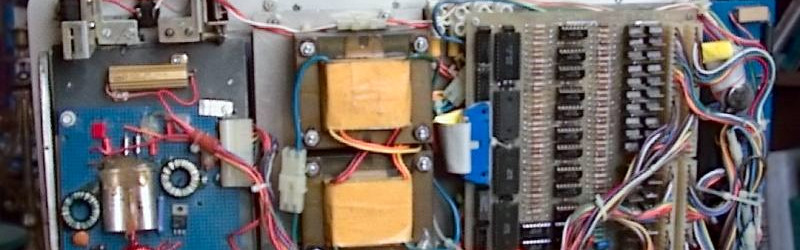

The system uses not one, but two Ataris. An ST has all the display data and scheduling set up in the Zoomracks card file software, this is then exported to an 800XL which does the work of running the display. We’re told the code for the 800XL is loaded on a ROM cartridge for reliability. The 800XL is mounted in an aluminium briefcase with a small CRT monitor and battery, and a custom interface board stuffed with TO220 power transistors to fire the pyrotechnics themselves.

It’s unlikely that you’ll be breaking out a vintage Atari yourselves to fun a firework show three decades later, but the opportunity to examine in detail a real-world contemporary commercial use of a now-vintage computer doesn’t come along too often. You can read the original article on the Internet Archive, and listen to the [Veline] interview on the podcast episode.

This is the first Atari firework controller we’ve brought you, but we’ve shown you plenty of others like this beautifuly-executed Arduino build. And if you wonder how to trigger the fireworks themselves, how about destroying a resistor?

The 8-bit Ataris were nice, in that the joystick ports worked of some sort of PIA, whatever the appropriate 6502 one is called. With the right POKEs (always POKEs, because like Commodore they didn’t bother writing the amazing graphics capabilities into the BASIC), you could change the 8 bits of joystick (UDLR x 2) into outputs. Then it’s a simple matter of a transistor on each, to drive whatever you like, relays being good for lots of things. I made up a board to do this as a school project.

While the UDLR inputs turned to outputs, you still had the fire buttons and potentiometer inputs (for paddles) available as inputs, so it was fairly versatile.

With a few register buffers you could expand to more outputs if you wanted to, make up your own addressing circuit.

A total of 16 pins of IO across the 4 joystick ports. I built a 4 channel box to control A/C outlets with optocouplers to triacs.

Atari also published the de re Atari manual that included every detail of how it all worked. It’s in the basement somewhere.

Back in that day every computer with more than three users had a manual available, usually for ten or fifteen dollars, that detailed everything you would ever need to know to write professional software for that machine — BIOS calls, register definitions, and all of it. I had the one for the C64. The IBM PC was the first widely owned computer to not have this information easily and publicly available, and set a terrible trend for the future. While there were sources like the pink-shirt book, none of them were really complete in the way that the earlier manuals were, and later you would need NDA’s and steep licence fees even to see the API’s for the most common operating systems and device drivers.

Back in the day, I used to run a DJ light show using a C64. The basic code was loaded via a cassette drive and used the POKE command to set pins on the expansion port high or low. I had a box with 5V relays that would sequence two bank of lights mounted on a truss. There were ~8 or so sequences that were selected by pressing the function keys. Very effective, reliable and much cheaper than the alternatives of the time.

I did similar with my C64, but I built a laser show. I built a board that fit into the expansion slot and decoded 3 addresses, two of those went to D/A converters and power op amps to drive galvanometers with first surface mirrors on them. The third address went to an ultra high speed rotary solenoid that acted as a shutter. That was a long time ago…..

Yep.Done the Atari PIA in the day. Made a software synthesizer with the old organ keyboard kit from Maplin using multiplexors driven from the ports.