Despite the fact that we’re rapidly approaching the year 2022, there are still an incredible number of gadgets out there that you’re expected to power with disposable batteries. Sure you can buy rechargeable stand-ins that come in the various shapes and sizes of the traditional alkaline cells, but that’s a stopgap at best. For some, if a new gadget doesn’t feature an internal Li-ion battery and standardized USB charging, it’s a non-starter.

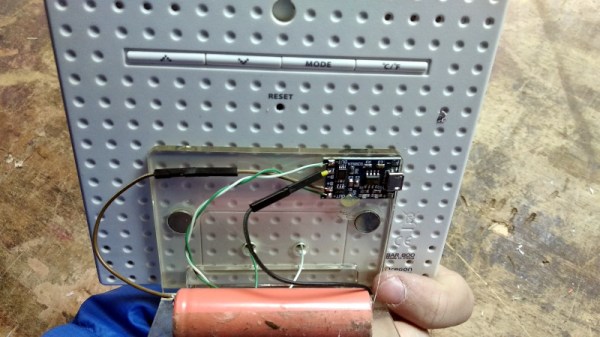

[Danilo Larizza] is one of those people. Bothered by the fact that his Oregon Scientific weather station required a pair of CR2032 coin cells, he set out to replace them with an integrated rechargeable solution. The conversion ending up being easier to implement than he initially expected, and by his calculations, his solution should keep the unit up and running for nearly 40 days before needing to be topped off with a standard USB charger.

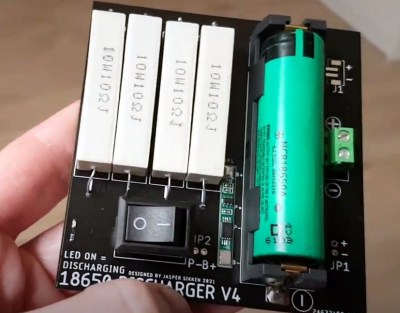

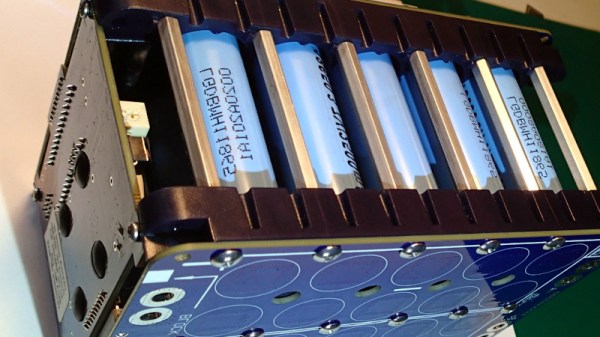

The first step was determining how much power it actually took to run the weather station. Although the two CR2032 cells were wired in series, and therefore providing a nominal 6 V, he determined through experimentation with a bench power supply that it would run on as little as 3.2 volts. This coincides nicely with the voltage range for a single 18650 cell, and meant he didn’t need to add a boost converter into the mix. He notes the weather station does flash a “Low Battery” warning most of the time now, but that seems a fair price to pay.

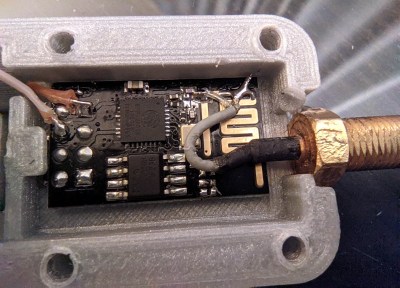

Confident in the knowledge that the weather station could happily run with an 18650 cell connected in place of the original CR2032s, all [Danilo] needed to do was figure out a way to charge the battery up from time to time. To that end, he reached for a common TP4056 module. This handy little board is a great match for 18650 cells, and is so cheap that there’s really no excuse not to have a few of them kicking around your parts bin. You never know when you might need to teach an old gadget new tricks.