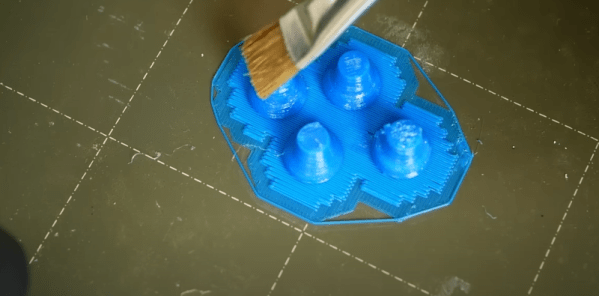

Back when 3D printers were pretty new, most of us had glass beds with or without painter’s tape. To make plastic stick, you’d either use a glue stick or hair spray. Many people have moved on to various other build surfaces that don’t require help, but some people still use something to make the bed sticky and there are quite a few products on the market that claim to be better than normal glue or hairspray. [Jonas] wanted to try it, but instead of buying a commercial product, he found a recipe online for “3D printer goop” and made it himself.

You need four ingredients: distilled water and isopropyl alcohol are easy to find. The other two chemicals: PVP and PVA powder, are not too hard to source and aren’t terribly dangerous to handle. The recipe was actually from [MakerBogans] who documents this recipe as “Super Goop” and has another formula for “Normal Goop.” You’ll probably have to buy the chemicals in huge quantities compared to the tiny amounts you really need.

We assume the shots of the 3D printer printing its first layer is showing how effective the glue is. This looks like a very simple thing to mix up and keep in a sprayer. If you have some friends, you could probably do a group buy of the chemicals and it would cost nearly nothing for the small amounts of chemicals you need.

If you don’t want to order exotic chemicals, you might not need them. We used to make “goop” by dissolving ABS in acetone, but hairspray usually did the trick.

Continue reading “Homebrew 3D Printer Goop Promises Better Bed Adhesion”

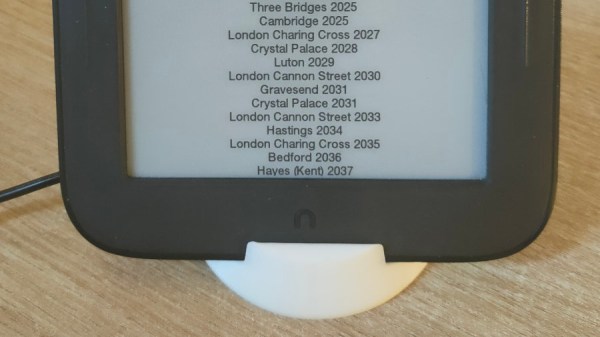

The soft touch layer on the back didn’t go away with help of alcohol, but by sheer luck, an acetone bottle was nearby, and an acetone scrub helped get rid of the unpleasant stickiness. The tablet’s charging circuitry turned out to be unsophisticated – the tablet wouldn’t boot from MicroUSB input, and [Jonathan] wired up 5 volts from a USB cable straight into the battery input. Mind you, this might not be advised, as Lithium-Ion battery range is from 3 volts to 4.2 volts and a regulator would be called for, but [Jonatron] says it’s been working just fine.

The soft touch layer on the back didn’t go away with help of alcohol, but by sheer luck, an acetone bottle was nearby, and an acetone scrub helped get rid of the unpleasant stickiness. The tablet’s charging circuitry turned out to be unsophisticated – the tablet wouldn’t boot from MicroUSB input, and [Jonathan] wired up 5 volts from a USB cable straight into the battery input. Mind you, this might not be advised, as Lithium-Ion battery range is from 3 volts to 4.2 volts and a regulator would be called for, but [Jonatron] says it’s been working just fine.