There was a time when most 3D printers used ABS, which is a great plastic for toughness, but is hard to print with since it tends to warp. Worse still, it stinks and the fumes may be bad for you. Most people have switched over to printing in PLA these days, but one thing you might miss with this more forgiving plastic is vapor smoothing with acetone; a smoothed print doesn’t show layer lines and looks more like plastic part that didn’t go through a nozzle.

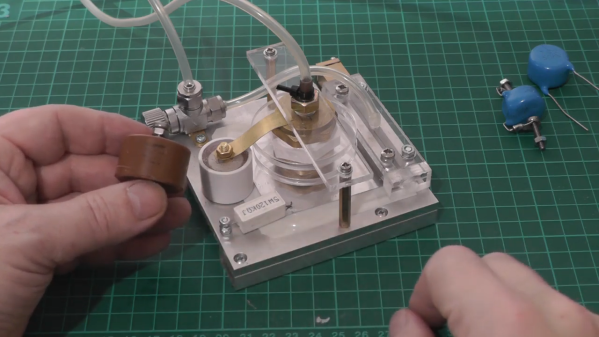

[Major Hardware] likes the look of vapor smoothed parts, but doesn’t like working with ABS and acetone fumes, so he’s started using Polysmooth. As you can see in the video below, the results look good, but be warned that the filament is relatively pricey. Plus you need to use a $300 machine that atomizes your alcohol into a mist. We feel certain you could do the same thing for less since it appears to just be like a humidifier, but we’d also suggest being careful putting flammable substances in a consumer-grade humidifier and certainly don’t use a vaporizer.

The filament sounds like it is on par with PLA for ease of printing. The material has a higher glass temperature than PLA but less than ABS. The tensile strength and Young’s modulus (a measure of stiffness) numbers are comparable to ABS. Although all smoothing has some imperfections and you probably need to experiment with times and other parameters. The smoothing did fuse some movable joints, so anything that moves or fits together is probably a bad candidate for this process. We’ve also heard that thin-walled parts can get soft in water due to alcohol residue, but you can dry or soak the part clean to avoid that.

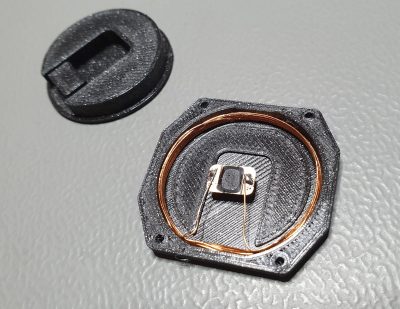

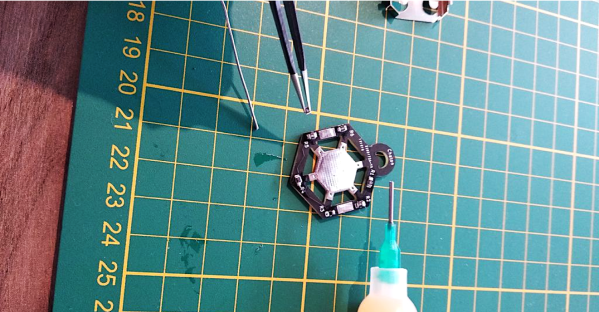

If you want to try your own hand at making a mist, this might get you started. After all, if it can handle acetone, we imagine alcohol isn’t any worse. While it isn’t as easy to handle as alcohol, we hear the solvents such as THF or ethyl acetate can smooth regular PLA. Heat guns and open flames are popular, too.