During the 1980s and 1990s Novell was one of those names that you could not avoid if you came even somewhat close to computers. Starting with selling computers and printers, they’d switch to producing networking hardware like the famous NE2000 and the inevitability that was Novell Netware software, which would cement its fortunes. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Novell began to face headwinds from a new giant: Microsoft, which along with the rest of the history of Novell is the topic of a recent article by [Bradford Morgan White], covering this rise, the competition from Microsoft’s Windows NT and its ultimate demise as it found itself unable to compete in the rapidly changing market around 2000, despite flirting with Linux.

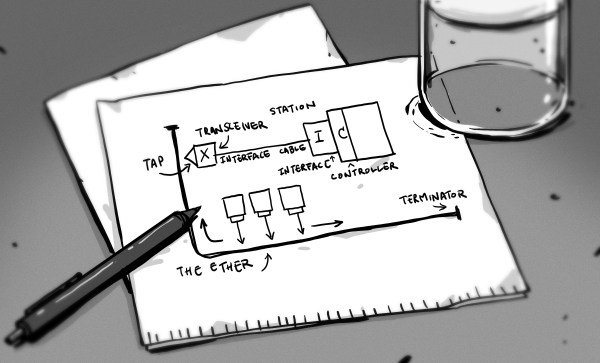

Novell was founded by two experienced executives in 1980, with the name being reportedly the misspelled French word for ‘new’ (nouveau or nouvelle). With NetWare having cornered the networking market, there was still a dearth of networking equipment like Ethernet expansion cards. This led Novell to introduce the 8-bit ISA card NE1000 in 1987, later followed by the 16-bit NE2000. Lower priced than competing products, they became a market favorite. Then Windows NT rolled in during the 1990s and began to destroy NetWare’s marketshare, leaving Novell to flounder until it was snapped up by Attachmate in 2011, which was snapped up by Micro Focus International 2014, which got gobbled up by Canada-based OpenText in 2023. Here Novell’s technologies got distributed across its divisions, finally ending Novell’s story.