[DiodeGoneWild]’s latest video lives up to the name. He takes apart a laser headlight to recover a pretty powerful blue laser. You can see the video, below.

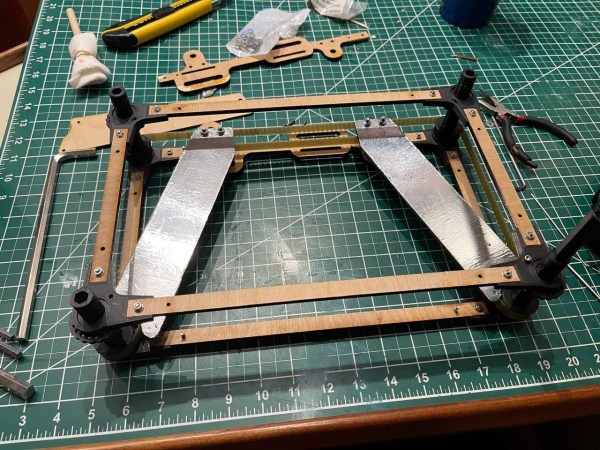

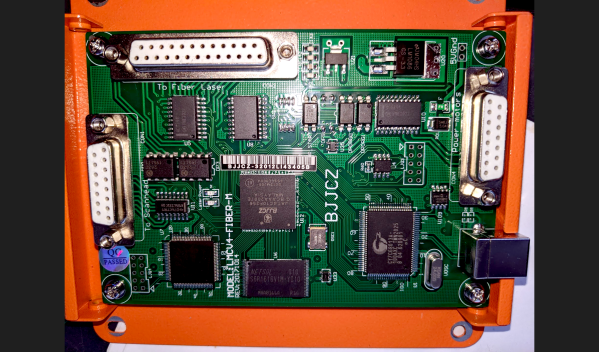

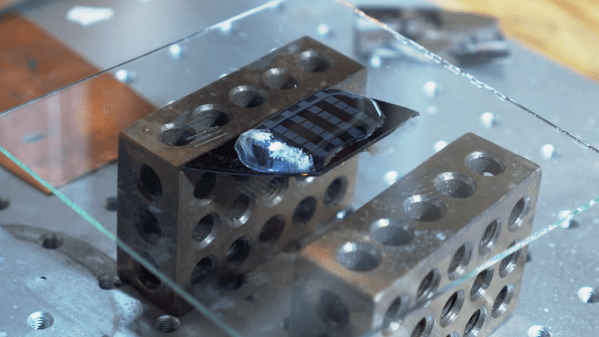

The headlights work with blue laser diodes that excite phosphor to produce white light. Removing the outside trappings revealed a three-pin laser diode (the case is the third pin). There’s also a substantial heatsink. Removing the diode from the assembly is difficult, but it is easy enough to leave it in the heatsink and use the existing connector.

Of course, the phosphor and a filter have to go. Some destructive work with a screwdriver and pliers broke out the optics from a diode he’d destroyed trying to remove it. Then he replaced the optics on the remaining diode with the modified housing.

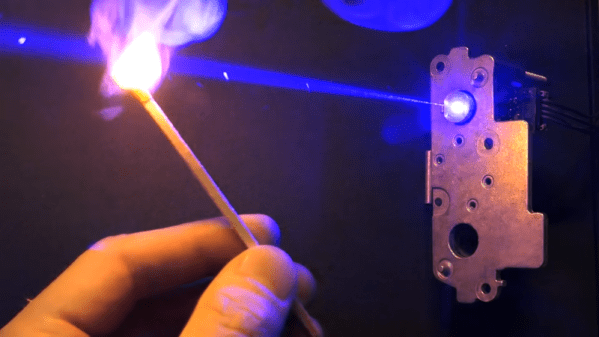

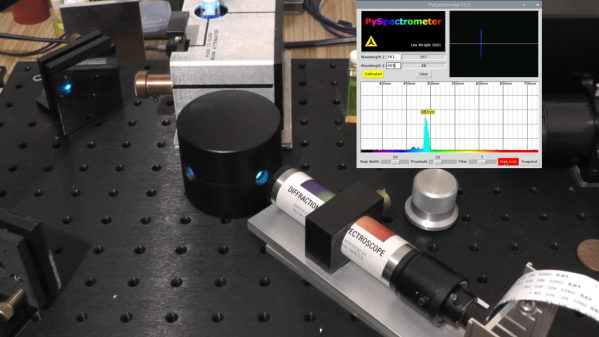

With a low-current test, the diode didn’t lase but did act as a regular LED. More current did the trick, though. The laser without the optics made a line rather than a spot but still had enough power to melt some plastic and light matches. To get a parallel beam, the internal lens needs to move closer to the diode, and a drill bit allowed that to happen, which reduced the beam’s divergence quite a bit, but didn’t create the best result.

With the proliferation of cheap laser modules, it is really worth scrapping a headlight? Maybe. But it is an interesting look inside of a modern headlight, either way. We’ve peeked inside these headlights before. Maybe you can turn those old headlights into an oven.

Continue reading “High-Power Laser Salvaged From Headlights”