When [Elixir of Progress] was looking at setting up environmental sensors around their home to keep track of temperature, humidity and such, the obvious ideas of using WiFi-connected sensors didn’t work due to lack of WiFi range. Although Zigbee (Z-wave) sensors have longer range than WiFi, they are decidedly more expensive, proprietary and require a special transceiver hub. That’s where 433 MHz sensors for weather stations come into the picture.

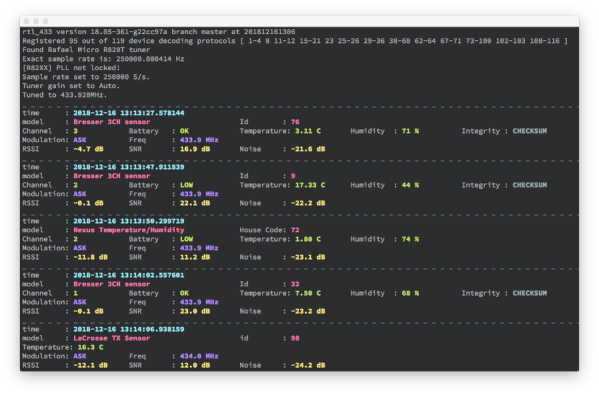

The idea is simple: virtually all of those sensors – many of them rated for outdoor use – use the unlicensed 433 MHz spectrum that can easily be captured using cheap RTL-SDR (software defined radio) USB dongles. With the data stream from these sensors captured, the open source rtl_433 project enables automatic decoding of these data streams for a wide range of supported sensors.

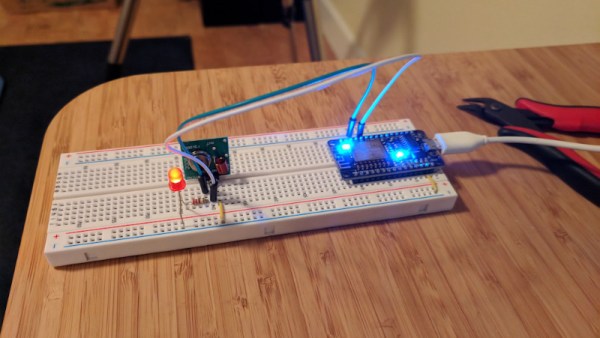

While Realtek RTL2832-based and other RTL-SDRs can be found for quite cheap, it should be noted that these can run quite hot. Rather than heatsinking the IC, for this project it was elected to only listen sporadically and allow the RTL-SDR receiver to cool down in between listening sessions.

Getting the data from there into Home Assistant, InfluxDB or similar is easy, as rtl_433 can output the decoded data directly to an Influx database, MQTT broker as well as other formats. In this case, the data was sent via MQTT with the Home Assistant instance configured to treat these MQTT topics as sensors. With each sensor’s location carefully registered, this allows for setting up a dense, very low-power network of 433 MHz sensors for monitoring and home automation purposes.