We live in an exciting time with respect to electrical power, one in which it has never been easier to break free from mains electricity, and low-frequency AC power in general. A confluence of lower-power appliances and devices using low-voltage external switch-mode supplies, readily available solar panels and electronic modules, and inexpensive high-capacity batteries, means that being your own power provider can be as simple as making an online order.

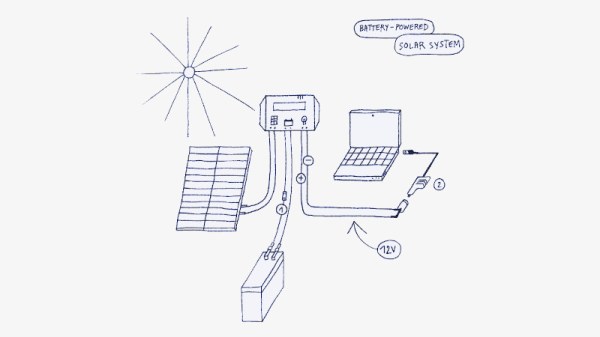

But which parts should you choose? Low Tech Magazine has the answer, in the form of a guide to building a small solar power system. The result is an extremely comprehensive guide, and though it’s written for a general audience there’s still plenty of information for the Hackaday reader.

Perhaps the most important part is that it’s demystifying the subject, there in front of us are a set of pretty straightforward recipes for personal power. The computer this is being written on spends a significant proportion of its time on the road with the ever-present company of a very hefty USB-C power pack for example, and the realization that a not-too-expensive solar panel and USB PD source could lessen the range anxiety and constant search for a train seat with a socket for a writer on the move is quite a powerful one.

Take a look and see whether your life could use bit of inexpensive off-grid power, meanwhile we’re quite pleased that the USB-C PD standard has eased some of the DC problems we expressed frustration at back in 2016.