Join us on Wednesday, March 10 at noon Pacific for the Decapping Components Hack Chat with John McMaster!

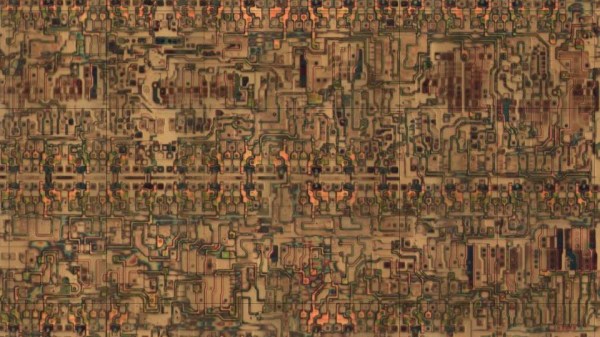

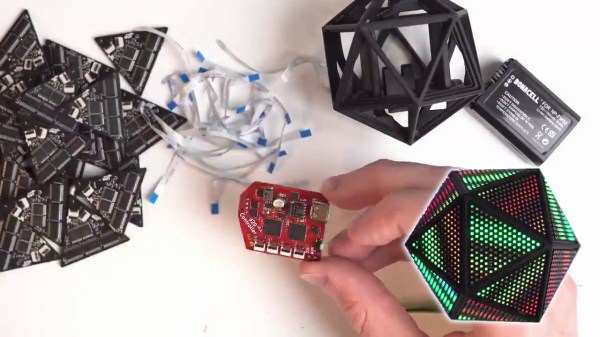

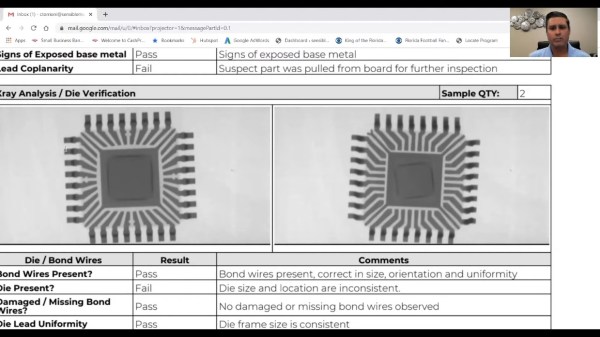

We treat them like black boxes, which they oftentimes are, but what lies beneath the inscrutable packages of electronic components is another world that begs exploration. But the sensitive and fragile silicon guts of these devices can be hard to get to, requiring destructive methods that, in the hands of a novice, more often than not lead to the demise of the good stuff inside.

To help us sort through the process of getting inside components, John McMaster will stop by the Hack Chat. You’ll probably recognize John’s work from Twitter and YouTube, or perhaps from his SiliconPr0n.org website, home to beauty shots of some of the chips he has decapped. John is also big in the reverse engineering community, organizing the Mountain View Reverse Engineering meetup, a group that meets regularly to discuss the secret world of components. Join us as we talk to John about some of the methods and materials used to get a look inside this world.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, March 10 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, March 10 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.

Continue reading “Decapping Components Hack Chat With John McMaster”