The Raspberry Pi HQ camera has appeared in a variety of builds since its introduction back in 2020, and has brought with it many opportunities for photographic projects to compete with the professionals. The latest we’ve been sent is from [Kevin McAleer], who has taken the camera with a full-size Pi and clothed it in a case very similar to the crop of mirror-less compact cameras.

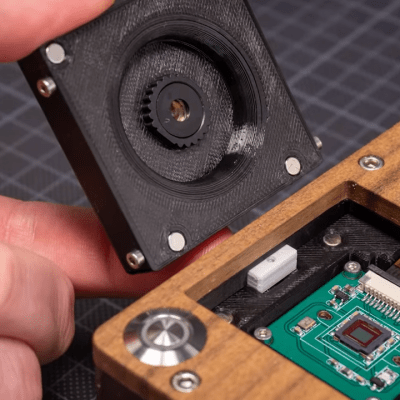

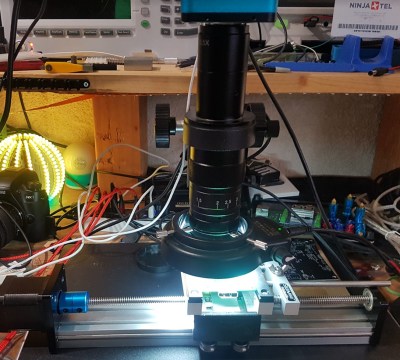

Inside the box is a Waveshare touchscreen that fits on the GPIO header, and a NanoWave 5000 mAH USB battery pack. The camera module fits on the front of the unit, with the C-mount ready to take a lens. Software is still a work in progress and is promised to be a Python script controlling the various camera programs. There are enough Pi camera projects for software to be a matter of choice and taste.

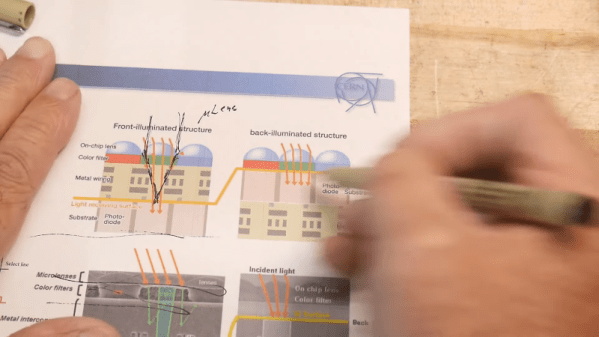

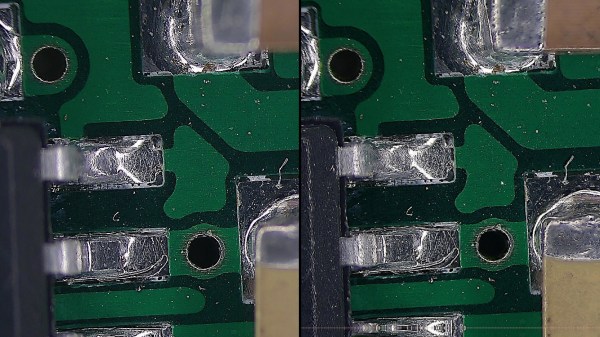

We like the form factor and we like the use of the very compact NanoWave battery, so we think this is a design with some possibilities. Perhaps a cover over the Pi ports might be of use though for general robustness in the face of everyday photography. The question remains though, whether it can come close to the performance of even a budget mirror-less compact camera, and we’re guessing that will depend as much on the operator skill, lens quality, and software capabilities as it does on the Pi HQ module. We look forward to seeing what comes of this project, but meanwhile you can see a video with all the details below the break.