Needless to say, we’re fascinated by LEDs, laser diodes, and other blinkies. Although we can get just about any light emitting thing, the data sheets aren’t always accurate or available. For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Ted] is building a device to characterize the efficiency, I/V curve, and optical properties of all the blinkies. It’s a project to make glowy stuff better, and a great entry for the Hackaday Prize.

The inspiration for this project came from two of [Ted]’s projects, one requiring response curves for LEDs, and laser diodes for another. This would give him a graph of optical output vs. current, angular light output distribution, and the lasing threshold for laser diodes. This data isn’t always available in the datasheet, so a homebrew tool is the only option.

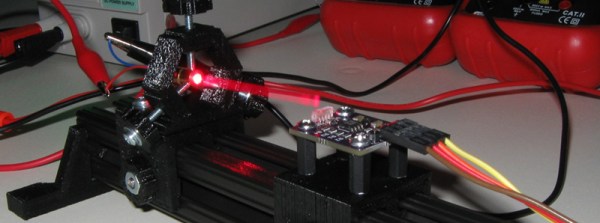

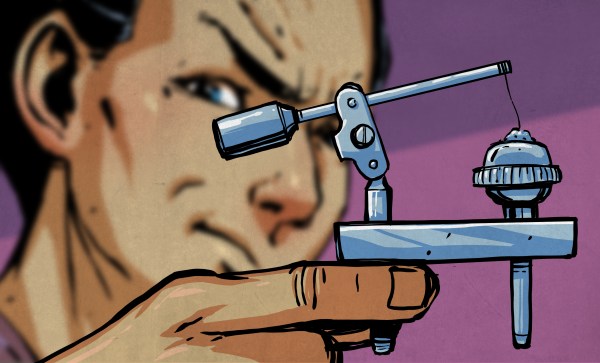

The high-level design of this tool is basically a voltmeter and ammeter measuring a glowy diode, producing IV curves and measuring optical output. That takes care of all the measurements except for the purely optical properties of a LED. This is measured by a goniometer, or basically putting the device under test on a carriage attached to a stepper motor and moving it past a fixed optical detector.

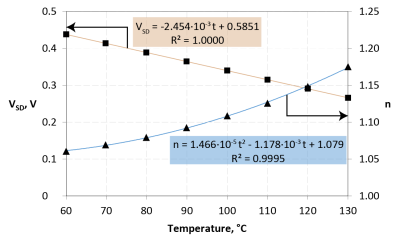

If you’re wondering why this device is needed and a simple datasheet is insufficient, check this out. [Ted] measured the efficiency of a Luxeon Z LED, and found the maximum efficiency is right around 10mA. The datasheet for this LED shows a nominal forward current of 500mA, and a maximum of 1000mA. If you just looked at the datasheet, you could easily assume a device powered for years by a coin cell would be impossible. It’s not, and [Ted]’s device gave us this information.