Every diabetic knows that one of the major burdens of the disease is managing supplies. From insulin to alcohol wipes, diabetes is a resource-intensive disease, and running out of anything has the potential for disaster. This is especially true for glucose test trips, the little electrochemical dongles that plug into a meter and read the amount of glucose in a single drop of blood.

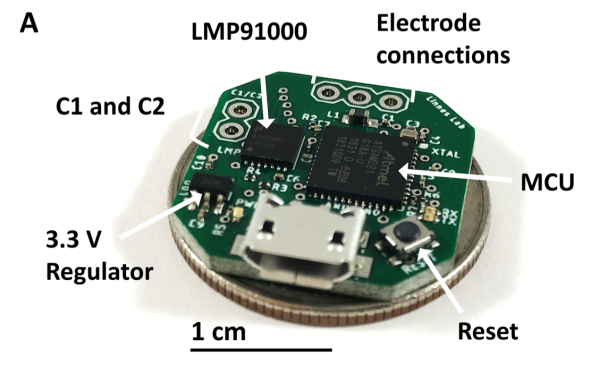

As you might expect, glucose test strips are highly proprietary, tightly regulated, and very expensive. But the chemistry that makes them work is pretty simple, which led [Markus Bindhammer] to these experiments with open source glucose testing. It’s all part of a larger effort at developing an open Arduino glucometer, a project that has been going on since 2016 but stalled in part thanks to supply chain difficulties on the chemistry side, mainly in procuring glucose oxidase, an enzyme that oxidizes glucose. The reaction creates hydrogen peroxide, which can be measured to determine the amount of glucose present.

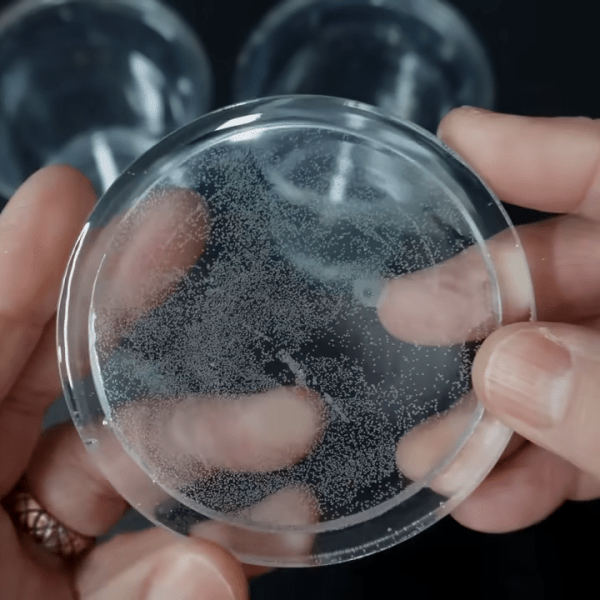

With glucose oxidase once again readily available — from bakery and wine-making suppliers — [Markus] started playing with the chemistry. The first reaction in the video below demonstrates how iodine and starch can be used as a reagent to detect peroxide. A tiny drop of glucose solution turns the iodine-starch suspension a deep blue color in the presence of glucose oxidase.

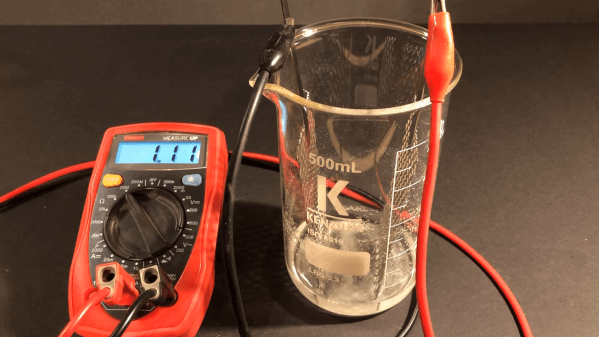

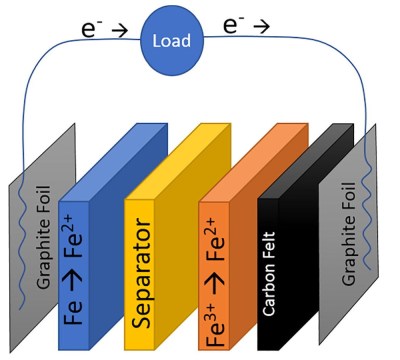

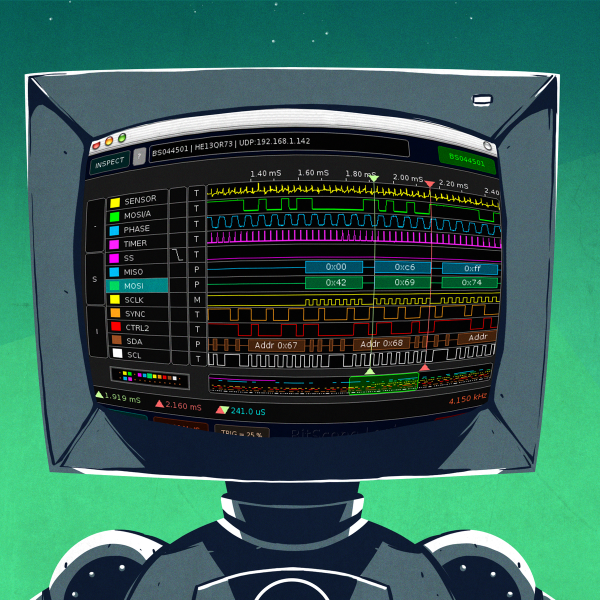

While lovely, colorimetric reactions such as these aren’t optimal for analyzing blood, so reaction number two uses electrochemistry to detect glucose. Platinum electrodes are bathed in a solution of glucose oxidase and connected to a multimeter. When glucose is added to the solution, the peroxide produced lowers the resistance across the electrodes. This is essentially what’s going on in commercial glucose test strips, as well as in continuous glucose monitors.

Hats off to [Markus] for working so diligently on this project. We’re keenly interested in this project, and we’ll be following developments closely. Continue reading “DIY Chemistry Points The Way To Open Source Blood Glucose Testing”