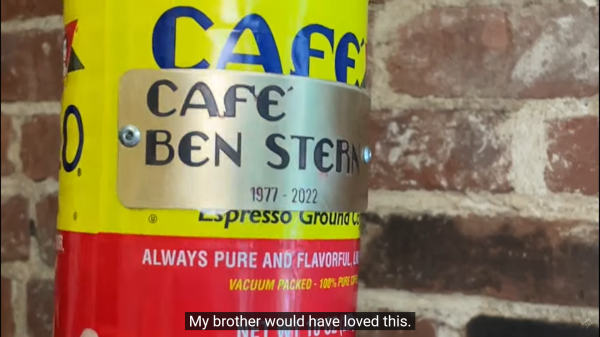

Brass plaques are eye-catching because no one makes them on a whim. They are more costly than wood or plastic, and processing them is proportionally difficult. [Becky Stern] picked the medium to honor her brother, who enjoyed coffee, motorcycles, and making things by hand. She made some playing card-sized pieces to adorn his favorite brand of hot bean juice and a large one to hang at his memorial site.

The primary components are a vertical salt water bath, DC power supply, metal to etch, scrap steel approximately the same size, and a water agitator, which in this case is an air pump and diffuser stone. You could stir manually for two hours and binge your shows but trust us and take the easy route. The video doesn’t explicitly call for flexible wires, but [Becky] wisely selected some high-strand hook-up leads, which will cause fewer headaches as stiff copper has a mind of its own, and you don’t want the two sides colliding.

There are a couple of ways to transfer an insulating mask to metal, and we see the ole’ magazine paper method fail in the video, but cutting vinyl works a treat. You may prefer lasers or resin printers, and that’s all right too. Once your mask is sorted, connect the positive lead to the brass and the negative to your steel. Now, it’s into the agitated salt water bath, apply direct current, and allow electricity to immortalize your design.

What do you do when you have a 10-gallon brew kettle (or any other stainless steel or aluminium thing) with no volume markings (or Hack a Day logos)? If you’re [Itsgus], you use science to

What do you do when you have a 10-gallon brew kettle (or any other stainless steel or aluminium thing) with no volume markings (or Hack a Day logos)? If you’re [Itsgus], you use science to