Downing] is no stranger to building portable consoles, employing all manner of techniques in the process. However, when it came time to start on this commission, [Downing] decided to take a different tack – employing a Form 2 SLA printer in this Nintendo 64 portable build.

Modifying home consoles to become portables often involves tricks like Frankencasing – hacking together original factory parts such as controllers, cases, and accessories, and using body filler and a lot of sanding to create a template for vacuum moulding, which then results in a seamless final product. It’s possible to get some really impressive results, but it does limit the builder to relying on existing parts.

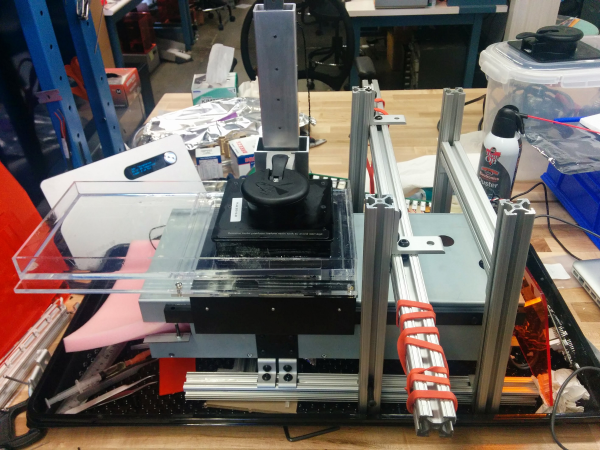

By using the Form 2, [Downing] was able to take advantage of the SLA printer’s ability to create parts with good surface finish that would normally require a lot of post-print finishing when 3D printed with more common FDM technology. This was particularly useful as it allowed the creation of custom buttons and small parts that “just fit” – normally such parts are made from stock pieces that are then modified.

The build also features a few other cool features – there’s a breakout box which allows the connection of extra controllers, as well as hosting AV out for hooking up to a television. The breakout box connects to the portable over an HDMI cable. It’s a tidy choice – it’s a standard cable that has an abundance of conductors available so you don’t have to be particularly tricky to get 3 controllers and a few analog signals talking over it.

In the end, [Downing] wouldn’t use SLA printing again for the case itself – the process was too slow and expensive. In this respect, FDM may require more work after printing but it still comes out ahead in terms of time and money. But for small custom parts like buttons and structural brackets, the Form 2 is the machine for the job.

Video after the break.