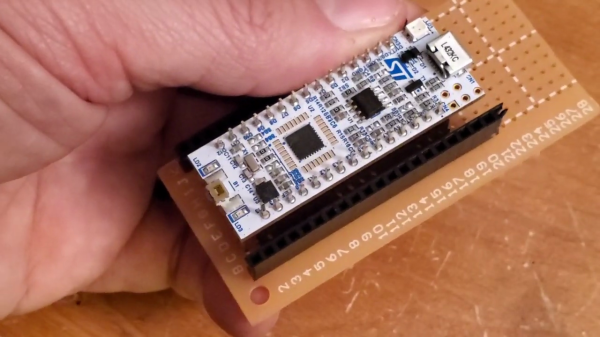

When you’re building a quick prototype or a one-off project it’s nice to be able to securely mount the various modules and development boards. Sometimes these boards have mounting holes, but often they don’t. As an example from the latter category, digital music instrument maker and performer [DIYDSP] shows us how to build a simple socket to mount an STM32 Nucleo-32 module.

The socket is built on a standard pad-per-hole piece of vector board cut to the desired size. Pairs of female pin header strips are soldered down to the board. The inner pair of headers is for the module, the outer pair is for your interconnections. The headers are connected up with short solder bridges, and [DIYDSP] recommends you extend the outer pair several pins longer than necessary. These extras can be used for additional power or ground points, or on some boards they could connect to the debug header pins. He prefers to use female sockets because that lessens the odds that an accidentally bent pin will short something out.

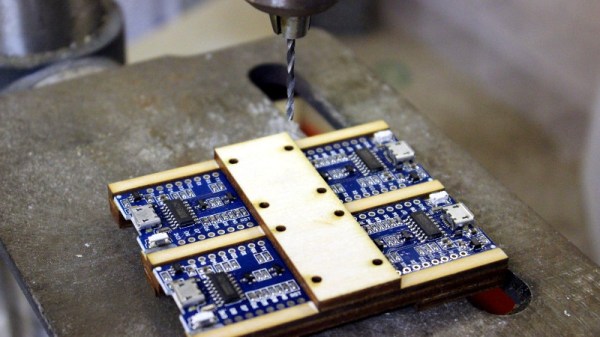

Final step is to drill your mounting holes in the desired location, and no more development boards free-floating and held up only by wires. Do you have any tips for mounting these kinds of modules, either individually as shown here or onto PCBs? Let us know in the comments.