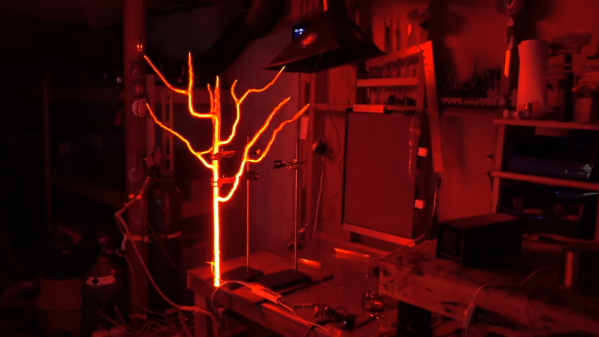

It wasn’t long after the development of the LED that LED watches became available. They were prized for their clear light output and low power draw. Neon bulbs, on the other hand, are thirsty for current and often warm or even hot in operation. And yet, [Lucas] found a way to build them into a sweet watch that actually does the job. Nice, right?

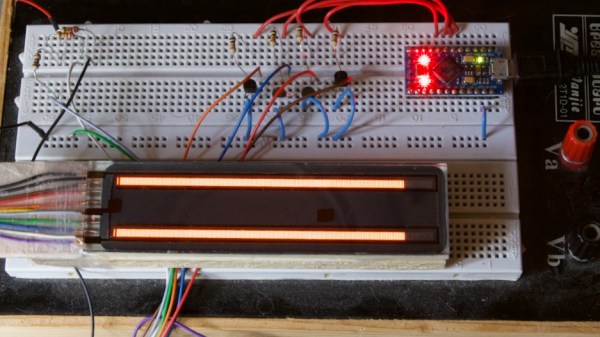

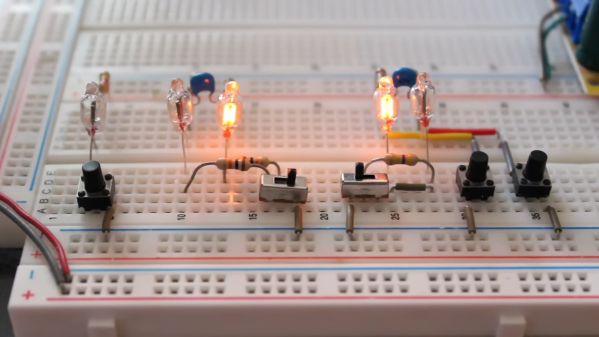

The design uses a simple trick to avoid killing the batteries with excessive power draw. The neon lamps are only activated when the user waves a hand above the watch, at which point the lamps light to display the time. Reading the time is a little fiddly, but understandable with the aid of this PDF diagram. Basically, the two electrodes of each neon lamp are driven independently. This gives each of the four lamps three possible states: with the first electrode lit, the second electrode lit, or both lit. Four lamps multiplied by three states equals 12—so the watch can display the hour quite easily. As for minutes, a similar scheme is used with some modifications for clarity. Setting the time is via a light sensor on the watch which picks up flashes from a computer screen.

It reminds us of a time when we once thought nixie tubes were too power hungry for a wristwatch build… until the hackers of the world proved us wrong. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Neon Watch Glows Rather Nicely, Tells Time”