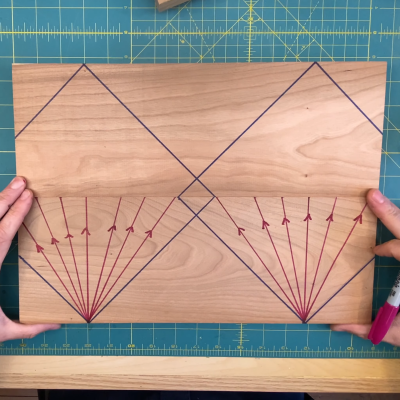

If you’re not a woodworker, you might not have heard of the “45-degree rule.” It goes like this: a clamp exerts a force that radiates out across a triangular region of the wood that forms a right angle — 45 degrees on each side of the clamp’s point of contact. So, to ensure that force is applied as evenly as possible across the entire glue joint, clamps should be spaced so that these force triangles overlap. It’s a handy rule, especially for the woodworker looking to justify the purchase of more clamps; you can never have too many clamps. But is it valid?

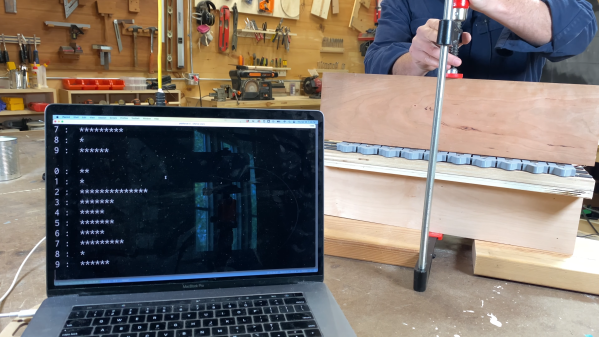

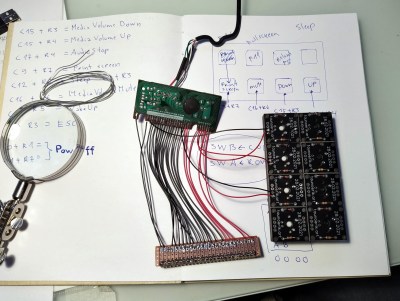

The short answer that [ari kardasis] comes up with in the video below is… sort of. With the help of a wonderfully complex array of strain gauges and a Raspberry Pi, he found that the story isn’t so simple. Each strain gauge lives in a 3D printed bracket that spaces the sensors evenly along the wood under test, with a lot of work going into making the test setup as stiff as possible with steel reinforcement. There were some problems with a few strain gauges, but once he sorted that out, the test setup went into action.

[ari] tested clamping force transmission through pieces of wood of various widths, using both hardwoods and softwoods. In general, he found that the force pattern is much broader than the 45-degree rule suggests — he got over 60 degrees in some cases. Softwoods seemed to have a somewhat more acute pattern than hardwoods, but still greater than the rulebook says. At the end of the day, it seems like clamp spacing of two board widths will suffice for hardwoods, while 1.5 or so will do for softwoods. Either way, that means fewer clamps are needed.

A lot of woodworking is seat-of-the-pants stuff, so it’s nice to see a more rigorous analysis like this. It reminds us a lot of some of the experiments [Matthia Wandel] has done, like load testing various types of woods and glues.

Continue reading “Exploring Woodworking Mysteries With Strain Gauges And Raspberry Pi”