At a time when practical graphical user interfaces were only just becoming a reality on desktop computers, Apple took a leap of faith and released one of the first commercially available mice back in 1983. It was criticized as being little more than a toy back then, but we all know how that particular story ends.

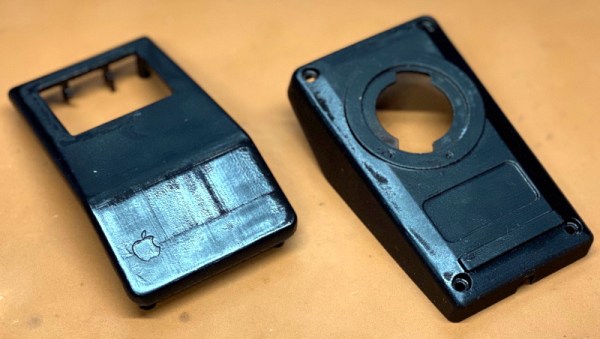

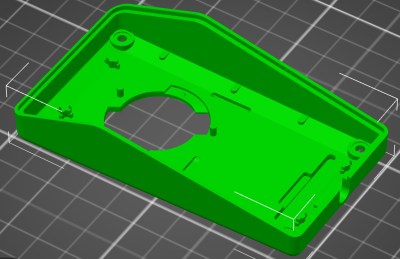

While the Apple G5431 isn’t that first mouse, it’s not too far removed. So much so that [Stephen Arsenault] believed it was worthy of historic preservation. Whether you want to print out a new case to replace a damaged original or try your hand at updating the classic design with modern electronics, his CAD model of this early computer peripheral is available under the Creative Commons license for anyone who wants it.

[Stephen] tells us that he was inspired to take on this project after he saw new manufactured cases for the G5431 popping up online, including a variant made out of translucent plastic. Realizing that a product from 1986 is old enough that Apple (probably) isn’t worried about people cloning it, he set out to produce this definitive digital version of the original case components for community use.

With these 3D models available, [Stephen] hopes that others will be inspired to try and modify the iconic design of the G5431. Perhaps by creating a Bluetooth version, or adding the ability to right-click. Considering we’ve already seen custom PCBs for mice, it’s hardly a stretch. We’d love to see somebody take him up on the offer, but even if not, the digital preservation of computer history is always welcome.