When SpaceX first showed off the thermal tiles on its Starship spacecraft that should keep it safe when re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere towards the loving embrace of the chopsticks on the launch tower, some similarity to the thermal tiles on NASA’s now retired Space Shuttle Orbiter was hard to miss.

Yet how similar are they really? That’s what the [Breaking Taps] channel on YouTube sought to find out, using an eBay-purchased chunk of Shuttle thermal tile along with bits of Starship tiles that washed ashore following the explosive end to the vehicle’s first integrated test last year.

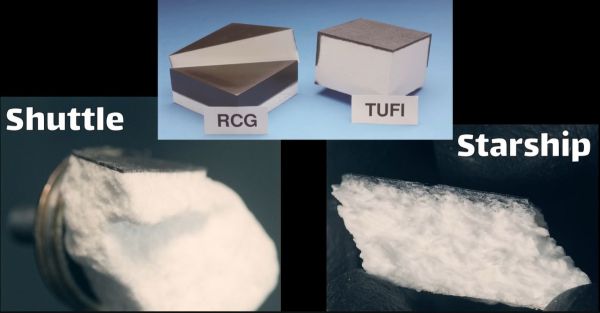

To answer the basic question: the SpaceX engineers responsible for the Starship thermal tiles seem to have done their homework. An analysis of not only the structure of the fibrous material, but also the black IR-blocking coating, shows that the Starship tiles are highly reminiscent of the EATB (introduced in 1996) tiles with TUFI (toughened unipiece fibrous insulation) coatings with added molybdenum disilicide, which were used during the last years of the Shuttle program.

TUFI is less fragile than the older RCG (reaction cured glass) coating, but also heavier, which is why few TUFI tiles were used on the Shuttles due to weight concerns. An oddity with the Starship tiles is that they incorporate many very large fibers, which could be by design, or indicative of something else.

Continue reading “How Different Are SpaceX Thermal Tiles From The Space Shuttle’s?”