It used to be that nearly every home had at least one decent high-voltage power supply. Of course, it was dedicated to accelerating electrons and slamming them into phosphors so we could bathe ourselves in X-rays (not really) while watching Howdy Doody. These days the trusty tube has been replaced with LEDs and liquid crystals, which is a shame because there’s so much fun to be had with tens of thousands of volts at your disposal.

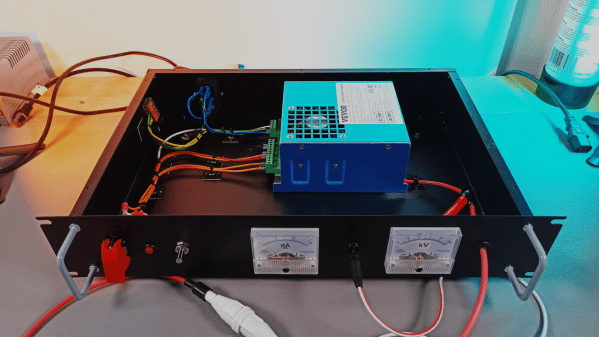

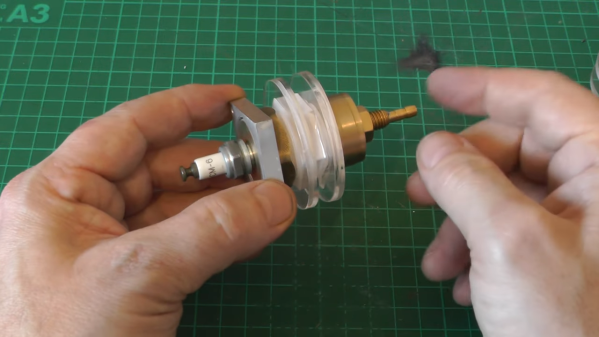

That’s the impetus behind this inexpensive high-voltage power supply by [Sebastian] over at Baltic Labs. The heavy lifting for this build is done by a commercially available power supply for a 50-watt CO2 laser tube, manufactured — or at least branded — by VEVOR, a company that seems intent on becoming the “Harbor Freight of everything.” It’s a bold choice given the brand’s somewhat questionable reputation for quality, but the build quality on the supply seems decent, at least from the outside. [Sebastian] mounted the supply inside a rack-mount case, as one does, and provided some basic controls, including the obligatory scary-looking toggle switch with safety cover. A pair of ammeters show current and voltage, the latter with the help of a high-voltage resistor rated at 1 gigaohm (!). The high-voltage feedthrough on the front panel is a little dodgy — a simple rubber grommet — but along with the insulation on the high-voltage output lead, it seems to be enough.

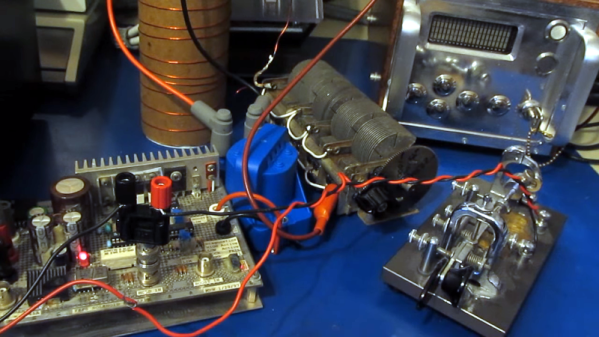

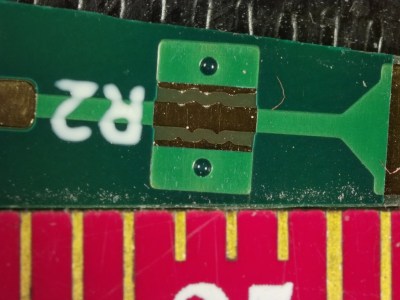

The power supply’s 30 kV output is plenty for [Sebastian]’s current needs, which from the video below appear to mainly include spark gap experiments. He does mention that 50 kV commercial supplies are available too, but it would be tough to do that for the $150 or so he spent on this one. There are other ways to go, of course — [Niklas] over at Advanced Tinkering recently shared his design for a more scratch-built high-voltage supply that’s pretty cool too. Whatever you do, though, be careful; we’ve been bitten by a 50 kV flyback supply before and it’s no joke.

Continue reading “High-Voltage Fun With An Inexpensive Power Supply”