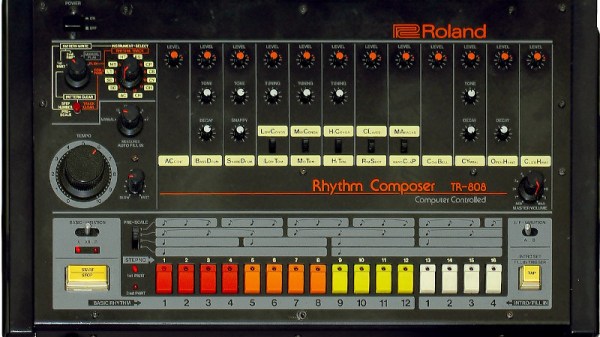

A culture in which it’s fair to say the community which Hackaday serves is steeped in, is electronic music. Within these pages you’ll find plenty of synthesisers, chiptune players, and other projects devoted to synthetic sound. Not everyone here is a musician of obsessive listener, but if Hackaday had a soundtrack album we’re guessing it would be electronic. Along the way, many of us have picked up an appreciation for the history of electronic music, whether it’s EDM from the 1990s, 8-bit SID chiptunes, or further back to figures such as Wendy Carlos, Gershon Kingsley, or Delia Derbyshire. But for all that, the origin of electronic music is frustratingly difficult to pin down. Is it characterised by the instruments alone, or does it have something more specific in the music itself? Here follows the result of a few months’ idle self-enlightenment as we try to get tot he bottom of it all.

Will The Real Electronic Music Please Stand Up?

Anyone reading around the subject soon discovers that there are several different facets to synthesised music which are collectively brought together under the same banner and which at times are all claimed individually to be the purest form of the art. Further to that it rapidly becomes obvious when studying the origins of the technology, that purely electronic and electromechanical music are also two sides of the same coin. Is music electronic when it uses an electronic instrument, when electronics are used to modify the sound of an acoustic instrument, when it is sequenced electronically often in a manner unplayable by a human, or when it uses sampled sounds? Is an electric guitar making electronic music when played through an effects pedal?

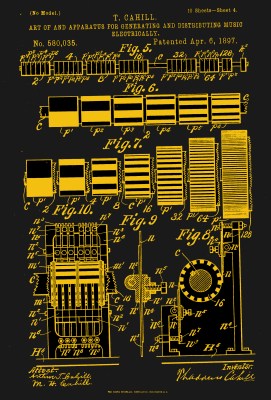

The history of electronic music as far as it seems from here, starts around the turn of the twentieth century, and though the work of many different engineers and musicians could be cited at its source there are three inventions which stand out. Thaddeus Cahill’s tone-wheel-based Telharmonium US patent was granted in 1897, the same year as that for Edwin S. Votey’s Pianola player piano, while the Russian Lev Termen’s Theremin was invented in 1919. In those three inventions we find the progenital ancestors of all synthesisers, sequencers, and purely electronic instruments. If it appears we’ve made a glaring omission by not mentioning inventions such as the phonograph, it’s because they were invented not to make music but to record it. Continue reading “Where Did Electronic Music Start?”