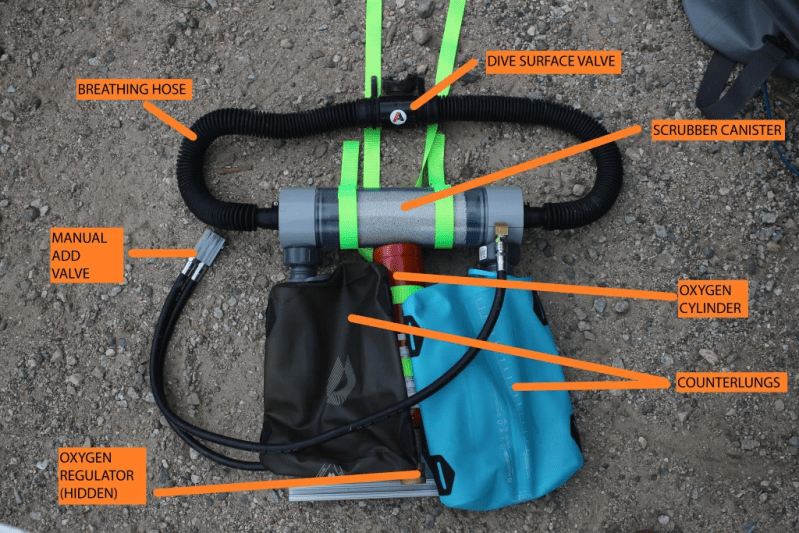

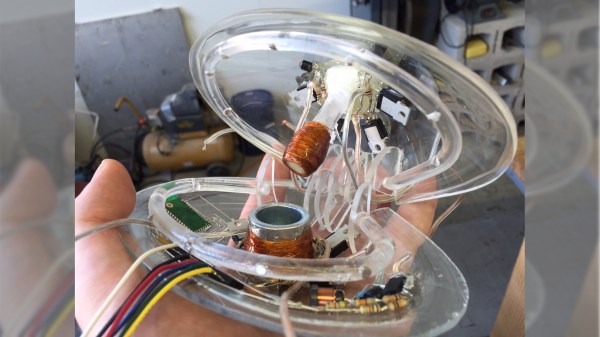

While the homebrew rebreather the [AyLo] describes on his blog looks exceptionally well engineered and is documented to a level we don’t often see, he still makes it very clear that he’s not suggesting you actually build one yourself. He’s very upfront about the fact that he has no formal training, and notes that he’s already identified several critical mistakes. That being said, he’s taken his rebreather out for a few dives and has (quite literally) lived to tell the tale, so he figured others might be interested in reading about his experiments.

For the landlubbers in the audience, a rebreather removes the CO2 from exhaled air and recirculates the remaining O2 for another pass through the lungs. Compared to open circuit systems, a rebreather can substantially increase the amount of time a diver can remain submerged for a given volume of gas. Rebreathers aren’t just for diving either, the same basic concept was used in the Apollo PLSS to increase the amount of time the astronauts could spend on the surface of the Moon.

The science behind it seemed simple enough, so [AyLo] did his research and starting designing a bare-minimum rebreather system in CAD. Rather than completely hack something together with zip ties, he wanted to take the time to make sure that he could at least mate his hardware with legitimate commercial scuba components wherever possible to minimize his points of failure. It meant more time designing and machining his parts, but the higher safety factor seems well worth the effort.

[AyLo] has limited the durations of his dives to ten minutes or less out of caution, but so far reports no problems with the setup. As with our coverage of the 3D printed pressure regulator or the Arduino nitrox analyser, we acknowledge there’s a higher than usual danger factor in these projects. But with a scientific approach and more conventional gear reserved for backups, these projects prove that hardware hacking is possible in even the most inhospitable conditions.

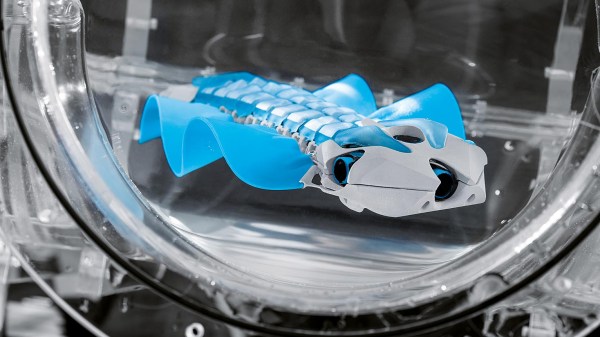

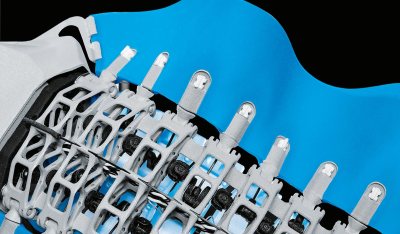

What was their elegant solution for making the fins undulate? Nine lever arms are attached to each fin. Those lever arms are controlled by two crankshafts which extend from the front of the body to the rear, one for each side. A servo motor then turns each crankshaft. Since the crankshafts are independent, that means each fin operates independently. This allows for turning by having one fin move faster than the other. A third motor in the head flexes the body, causing the robot to swim up or down.

What was their elegant solution for making the fins undulate? Nine lever arms are attached to each fin. Those lever arms are controlled by two crankshafts which extend from the front of the body to the rear, one for each side. A servo motor then turns each crankshaft. Since the crankshafts are independent, that means each fin operates independently. This allows for turning by having one fin move faster than the other. A third motor in the head flexes the body, causing the robot to swim up or down.

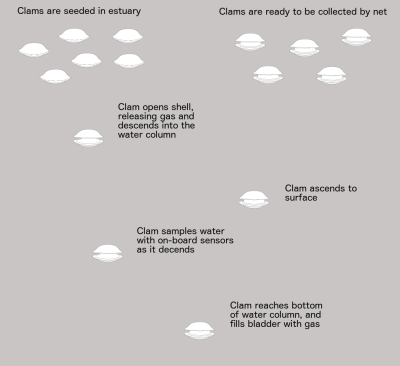

The clams contain the electronics, sensors, and means of descending and ascending within their shells. A bunch of them are dropped overboard on the surface. Their shells open, allowing the gas within to escape and they sink. As they descend they sample the water. When they reach the bottom, gas fills a bladder and they ascend back to the surface with their data where they’re collected in a net.

The clams contain the electronics, sensors, and means of descending and ascending within their shells. A bunch of them are dropped overboard on the surface. Their shells open, allowing the gas within to escape and they sink. As they descend they sample the water. When they reach the bottom, gas fills a bladder and they ascend back to the surface with their data where they’re collected in a net.