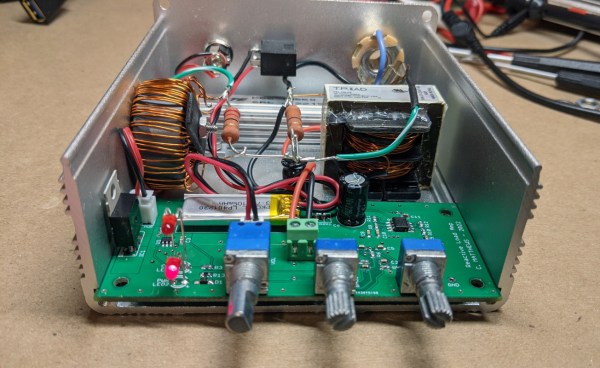

Metalworking might conjure images of large furnaces powered by coal, wood, or electricity, with molten metal sloshing around and visible in its crucible. But metalworking from home doesn’t need to use anything more fancy than a microwave, at least according to [Denny] a.k.a. [Shake the Future]. He has a number of metalworking tools designed to melt metal using a microwave, and in this video he uses them to make a usable aluminum pencil with a graphite core.

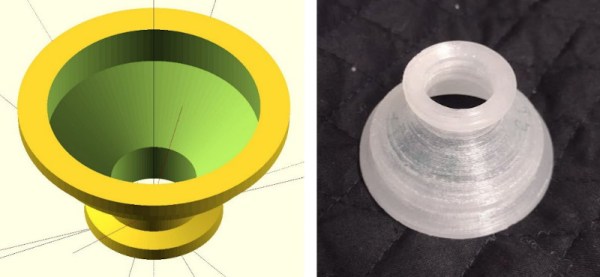

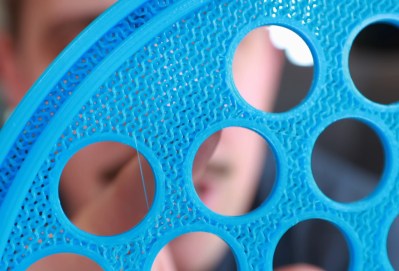

Before getting to the microwave kiln, the pencil mold needs to be prepared. A 3D-printed pencil is first created with the graphite core, and then [Denny] uses a plaster of Paris mixture to create the mold for the pencil. The 3D printed plastic is left inside the mold and placed in the first microwave kiln, which is turned on just enough to melt the plastic out of the mold, leaving behind the graphite core. From there a second kiln goes into the microwave to melt the aluminum.

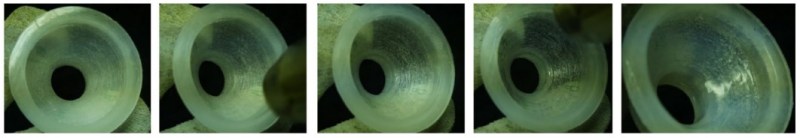

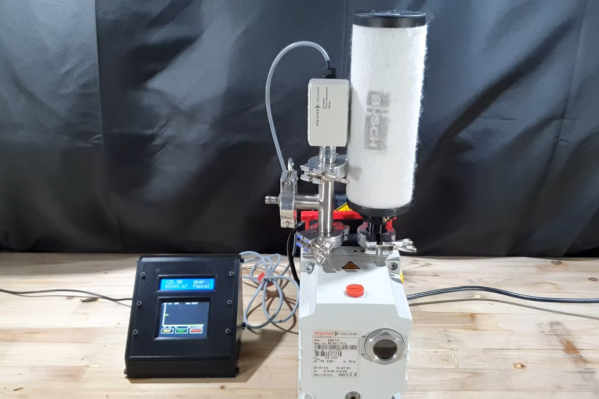

Once the molten aluminum is ready, it is removed from the kiln and poured in the still-warm pencil mold. This is where [Denny] has another trick up his sleeve. He’s using a household vacuum cleaner to suck the metal into place before it cools, creating a rudimentary but effective vacuum forming machine. The result is a working pencil, at least after he wears down a few razor blades attempting to sharpen the metal pencil. For more information about how [Denny] makes these microwave kilns, take a look at some of his earlier projects.

Continue reading “Casting Metal With A Microwave And Vacuum Cleaner”