When the automobile industry really began to take off in the 1930s, radar was barely in its infancy, and there was no reason to think something that complicated would ever make its way into the typical car. Yet here we stand less than 100 years later, and radar has been perfected and streamlined so much that an entire radar set can be built on a single chip, and commodity radar modules can be sprinkled all around the average vehicle.

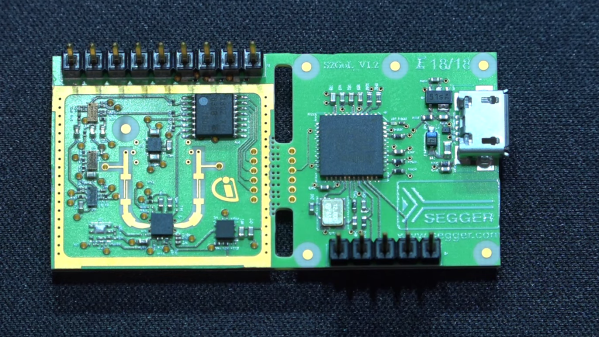

Looking inside these modules is always fascinating, especially when your tour guide is [Shahriar Shahramian] of The Signal Path, as it is for this deep dive into an Infineon 24-GHz automotive radar module. The interesting bit here is the BGT24LTR11 Doppler radar ASIC that Infineon uses in the module, because, well, there’s really not much else on the board. The degree of integration is astonishing here, and [Shahriar]’s walk-through of the datasheet is excellent, as always.

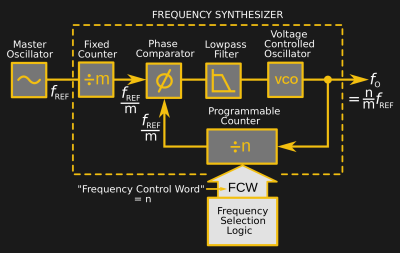

Things get interesting once he gets the module under the microscope and into the X-ray machine, but really interesting once the RF ASIC is uncapped, at the 15:18 mark. The die shots of the silicon germanium chip are impressively clear, and the analysis of all the main circuit blocks — voltage-controlled oscillator, power amps, mixer, LNAs — is clear and understandable. For our money, though, the best part is the look at the VCO circuit, which appears to use a bank of fuses to tune the tank inductor and keep the radar within a tight 250-Mz bandwidth, for regulatory reasons. We’d love to know more about the process used in the factory to do that bit.

This isn’t [Shahriar]’s first foray into automotive radar, of course — he looked at a 77-GHz FMCW car radar a while back. That one was bizarrely complicated, though, so there’s something more approachable about a commodity product like this.

Continue reading “Take A Deep Dive Into A Commodity Automotive Radar Chip”