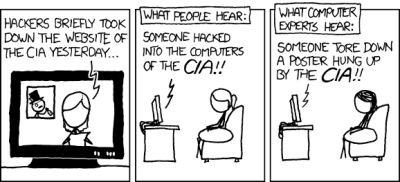

Maybe it’s the silly season of high summer, or maybe a PR bunny at a cybersecurity company has simply hit the jackpot with a story syndicated by the Press Association, but the non-tech media has been earnestly talking about a call upon the Cambridge Dictionary to remove the word “illegal” from their definition of “Hacker”. The weighty tome from the famous British university lists the word as either “a person who is skilled in the use of computer systems, often one who illegally obtains access to private computer systems:” in its learners dictionary, or as “someone who illegally uses a computer to access information stored on another computer system or to spread a computer virus” in its academic dictionary. The cybersecurity company in question argues that hackers in fact do a lot of the work that improves cybersecurity and are thus all-round Good Eggs, and not those nasty computer crooks we hear so much about in the papers.

We’re right behind them on the point about illegality, because while there are those who adopt the hacker sobriquet that wear hats of all colours including black, for us being a hacker is about having the curiosity to tinker with anything presented to us, whatever it is. It’s a word that originated among railway modelers (Internet Archived version), hardly a community that’s known for its criminal tendencies!

Popular Usage Informs Definition

It is however futile to attempt to influence a dictionary in this way. There are two types of lexicography: Prescriptive and Descriptive. With prescriptive lexicography, the dictionary instructs what something must mean or how it should be spelled, while descriptive lexicography tells you how something is used in the real world based on extensive usage research. Thus venerable lexicographers such as Samuel Johnson or Noah Webster told you a particular way to use your English, while their modern equivalents lead you towards current usage with plenty of examples.

It’s something that can cause significant discontent among some dictionary users as we can see from our consternation over the word “hacker”. The administration team at all dictionaries will be familiar with the constant stream of letters of complaint from people outraged that their pet piece of language is not reflected in the volume they regard as an authority. But while modern lexicographers admit that they sometimes walk in an uneasy balance between the two approaches, they are at heart scientists with a rigorous approach to evidence-based research, and are very proud of their efforts.

Big Data Makes for Big Dictionaries

Lexicographic research comes from huge corpora, databases of tens or hundreds of millions of words of written English, from which they can extract the subtlest of language trends to see where a word is going. These can be interesting and engrossing tools for anyone, not just linguists, so we’d urge you to have a go for yourself.

Lexicographic research comes from huge corpora, databases of tens or hundreds of millions of words of written English, from which they can extract the subtlest of language trends to see where a word is going. These can be interesting and engrossing tools for anyone, not just linguists, so we’d urge you to have a go for yourself.

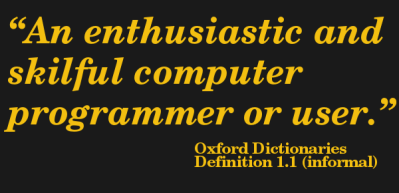

Sadly for us the corpus evidence shows the definition for “Hacker” has very firmly trended toward the tabloid newspaper meaning that associates cybercriminality. All we can do is subvert that trend by doing our best to own the word as we would prefer it to be used, re-appropriating it. At least the other weighty tome from a well-known British university has a secondary sense that we do agree with: “An enthusiastic and skilful computer programmer or user“.

Disclosure: Jenny List used to work in the dictionary business.