If it weren’t for persistence of vision, that quirk of biochemically mediated vision, life would be pretty boring. No movies, no TV — nothing but reality, the beauty of nature, and live performances to keep us entertained. Sounds dreadful.

We jest, of course, but POV is behind many cool hacks, one of which is [Joe]’s neat Nipkow disk clock. If you think you’ve never heard of such a thing, you’re probably wrong; Nipkow disks, named after their 19th-century inventor Paul Gottlieb Nipkow, were the central idea behind the earliest attempts at mechanically scanned television. Nipkow disks have a series of evenly spaced, spirally arranged holes that appear to scan across a fixed area when rotated. When placed between a lens and a photosensor, a rudimentary TV camera can be made.

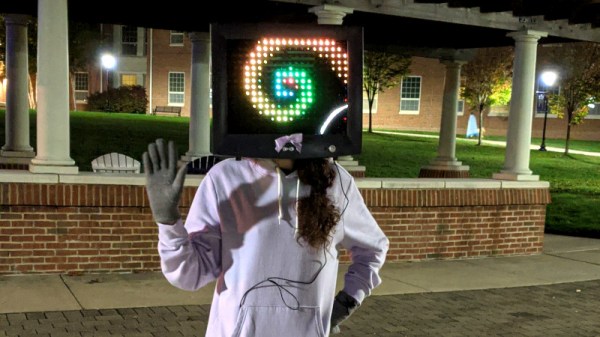

For his Nipkow clock, though, [Joe] turned the idea around and placed a light source behind the rotating disk. Controlling when and what color the LEDs in the array are illuminated relative to the position of the disk determines which pixels are illuminated. [Joe]’s clock uses two LED arrays to double the size of the display area, and a disk with rectangular apertures. The resulting pixels are somewhat keystone-shaped, but it doesn’t really distract from the look of the display. The video below shows the build process and the finished clock in action.

The key to getting the look right in a display like this is the code, and [Joe] put in a considerable effort for his software. If only the early mechanical TV tinkerers had had such help. [Jenny List] did a nice write-up on the early TV pioneers and their Nipkow disk cameras; we’ve also seen other Nipkow displays before, but [Joe]’s clock takes the concept to another level.