Everybody should have a few smoke alarms in their house, and everyone should go check the battery in their smoke alarm right now. That said, there are a few downsides to the traditional smoke alarm. They only work where you can hear them, and this problem has been solved over and over again by security companies and Internet of Things things.

Instead of investing in smart smoke alarms, [Johan] decided to build his own IoT smoke alarm. It’s dead simple, costs less than whatever wonder gizmo you can buy at a home improvement store, and reuses your old smoke alarm. In short, it’s everything you need to build an Internet-connected smoke alarm.

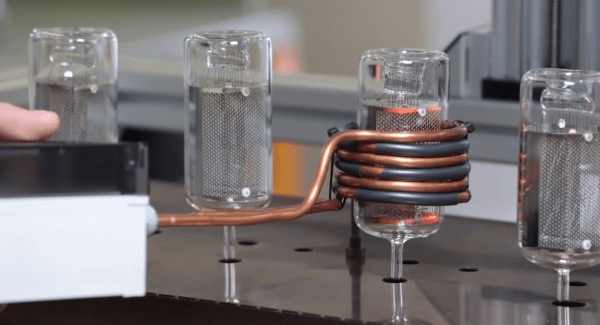

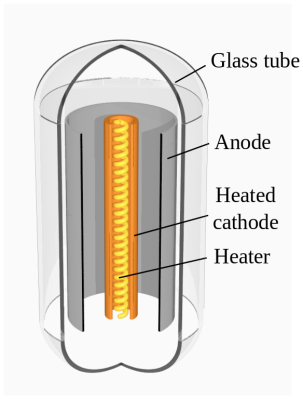

Smoke alarms, or at least ionization-based alarms with a tiny amount of radioactive americium, are very simple devices. Inside the alarm, there’s a metal can – an ionization chamber – with two metal plates. When smoke enters this chamber, a few transistors sound the alarm. If you’ve ever taken one apart, you can probably rebuild the circuit from memory.

Because these alarms are so simple, it’s possible to hack in some extra electronics into a design that hasn’t changed in fifty years. For [Johan]’s project, he’s doing just that, tapping into one of the leads on the ionization chamber, measuring the current through the buzzer, and adding a microcontroller with Bluetooth connectivity.

For the microcontroller and wireless solution, [Johan] has settled on TI’s CC2650 LaunchPad. It’s low power, relatively cheap, allows for over the air updates, and has a 12-bit ADC. Once this tiny module is complete, it can be deadbugged into a smoke alarm with relative ease. Any old phone can be used as a bridge between the alarm network and the Internet.

The idea of connecting a smoke alarm to the Internet is nothing new. Security companies have been doing this for years, and there are dozens of these devices available at Lowes or Home Depot. The idea of retrofitting smarts into a smoke alarm is new to us, and makes a lot of sense: smoke detectors are reliable, cheap, and simple. Why not reuse what’s easy and build out from there?