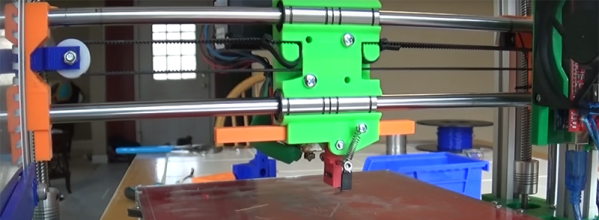

Automatic bed leveling is the next killer feature that will be found on all commercial filament printers. It’s a problem that has been solved a few dozen times already; there are just so many ways you can go about it. The Printrbot uses an inductive sensor to determine the position of the metal bed in relation to the nozzle. The Lulzbot Mini touches the nozzle itself to four contacts on the corner of the bed. There are even a few projects that will mechanically level the bed with the help of a system of cams and springs. It’s a difficult problem, and none of these solutions are perfect. [mjrice] has been thinking about the problem, and he hit upon a solution that is simple, elegant, and can be replicated on a 3D printer. It’s the RepRap solution to 3D printing, and it looks cool, to boot.

Instead of using the nozzle as a contact, getting an inductive sensor, or fabricating a baroque system of gears and cams, [mjrice] is doing this the old-fashioned way: a simple microswitch, the same type of switch you would find on the limit switches of any RepRap. Having a switch at the same Z position as a nozzle is an iffy idea, so [mjrice] made this switch retract into the extruder during printing, without using any motors, servos, or other electromechanical contrivances.

The key to this setup is a simple spring and a rack gear. When this rack gear is hit from the left side, it moves an arm and places the switch down on the bed. Hit the rack from the right side, and the switch folds up into the extruder. Combine this with a bit of G-code at the beginning of the print, and the switch will move down, figure out the actual height of the bed, and flip up out of the way. Beautiful, elegant, and the algorithms for bed leveling are already in most major printer firmwares.

You can check out the video of the mechanism below. It’s a great little device, and since it’s on a RepRap first, it’s not going to show up in a proprietary 3D printer next.

Continue reading “Rethinking Automated Bed Leveling For 3D Printers”

It is possible to print in color

It is possible to print in color