The early days of electricity appear to have been a cutthroat time. While academics were busy uncovering the mysteries of electromagnetism, bands of entrepreneurs were waiting to pounce on the pure science and engineer solutions to problems that didn’t even exist yet, but could no doubt turn into profitable ventures. We’ve all heard of the epic battles between Edison and Tesla and Westinghouse, and even with the benefit of more than a century of hindsight it’s hard to tell who did what to whom. But another conflict was brewing at the turn of 19th century, this time between an Indian polymath and an Italian nobleman, and it would determine who got credit for laying the foundations for the key technology of the 20th century – radio.

Hacking When It Counts: The Great Depression

In the summer of 1929, it would probably have been hard for the average Joe to imagine the degree to which his life was about to change. In October of that year, the US stock market tumbled, which in concert with myriad economic factors kicked off the Great Depression, a worldwide economic disaster that would send ripples through history to this very day. At its heart, the Depression was about a loss of confidence, manifested in bank failures, foreclosures, unemployment, and extreme austerity. People were thrust into situations for which they were ill-prepared, and if they were going to survive, they needed to adapt and do what they could with what they had on hand. In short, they needed to hack their way out of the Depression.

Social Hacking: Welcome to the Jungle

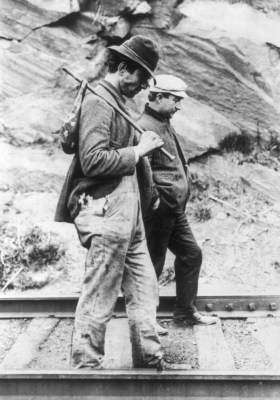

One reaction to the change in the social contract in the 1930s was increased vagrancy. While homelessness was certainly thrust upon some people by circumstances – in the depth of the Depression in 1933, something like 25% of men were unemployed, after all – life on the road was clearly a choice for millions. A typical story was that of the bored teenage boy, facing no prospects for a job and wishing to relieve his large family of the burden of one more mouth to feed. Hitting the road with a few possessions in his “bindle,” he learned the craft of life on the road from more experienced vagrants. And thus another hobo was created.

The popular image of the hobos as unique to the Depression is a little awry. Economic upheaval certainly swelled their ranks, but in America, hobos had first appeared after the Civil War, with war-weary veterans riding the rails looking for work. By the time the Depression hit, there was an extensive hobo culture in the United States, complete with its own slang and a rough code of ethics.

Hobos were top of the heap in the vagrant hierarchy, the “knights of the road.” They were migrant workers, generally unskilled, willing to stay in one place for a paying job but unwilling to commit to settling down. When the job was done or he had made enough money, he moved on. Tramps were the next step down – wanderers who were willing to work but only when absolutely necessary. Lowest in the pecking order were the bums who stayed put and relied on the kindness of strangers for their survival. Regardless of rank, all the vagrants had one thing in common – the road. More or less constantly on the move, they had to quickly learn how to provide for themselves without the creature comforts, which before the Depression hit had begun to include many modern conveniences.

Cooking arrangements were one thing hobos excelled at, whether on the road or in one of the many hobo camps, or jungles, that sprung up at railroad crossings outside of towns. A campfire in a ring of rocks is the traditional view of outdoor cookery, but the hobos quickly learned that it’s not terribly fuel-efficient. One solution to this problem was the hobo stove, an ancestor of the rocket stove. Relying on convection to draw a huge volume of air into a combustion chamber, hobo stoves were easily fabricated from tin cans and other metal scraps that were easy to come by in a world before recycling and large municipal landfills. Most were assembled on the spot and served for a meal or two before being abandoned, but some actually had insulation between double walls and clever arrangements of the fuel shelf to feed automatically as the fuel burned away. Scraps of wood, pinecones, newspapers and cardboard – a hobo stove will eat almost anything, and burn hot enough that even damp fuel isn’t a problem.

Often finding himself with time on his hands, many a hobo kept himself busy with arts and crafts projects in camp. Making hobo nickels was a popular way to pass the time, and often resulted in a trade item far more valuable than the base value of the starting material. The Indian head figure on the US Buffalo nickels of the day were modified with tools fabricated from old nails and files; metal was pushed around the coin to create features on the figure, usually a bowler hat and facial hair. A ‘bo could trade the miniature bas-relief sculpture for a good meal; today genuine hobo nickels from the Depression era command high prices from collectors.

Radio: Razor Blades and Copper Pipe

Unless the hobo was flopping in town or at a really well-equipped jungle, chances are pretty good he wasn’t listening to the radio too much. From our 21st century outlook, it’s sometimes hard to appreciate how new and exciting radio was and the impact it had on everyday life in America during the Depression. Radio connected the nation in a way no other medium ever had. That the Depression did not kill this infant technology in its cradle is a testament to both its power as a medium – families would stop making payments on almost everything else so they could keep their radio sets – and to the tenacity of early electronics hobbyists, who learned to keep radios alive and even to fabricate them from almost nothing.

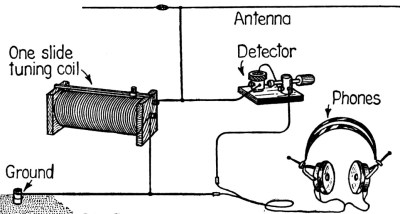

Although tube-type superheterodyne receivers were widely available all through the Depression, crystal sets were still a popular and sometimes necessary hacker project during the Depression. Relying on nothing more than a tuned circuit and a detector connected to an antenna and high-impedance headphones, a crystal set was able to pick up strong AM broadcasts and sometimes even shortwave stations. The earliest detectors were crystals of galena probed by a tiny “cat’s whisker” wire, but metal oxides could also form the necessary rectifying junction, leading to detectors built out of razor blades and safety pins. Crystal radio skills would serve many a Depression-era farm boy well during the next decade as they went off to war in Europe and the Pacific; there they created foxhole radios to listen in on broadcasts without the risk of a more sophisticated radio set, whose local oscillator could be detected by the enemy.

Receivers weren’t the only area in which Depression-era hackers made an impact. As commercial broadcasting took off, so did amateur radio, and few commercial transmitters were available to satisfy the burgeoning ham market. Depression-era hams had to home-brew almost everything and came up with some beautiful designs that modern glowbug hams recreate with loving attention to detail. A popular transmitter back in the day was based on the Hartley oscillator (PDF link). Using only a single triode tube and a tuned circuit with coils wound from 1/4″ copper tubing, Hartley transmitters could be built on a literal breadboard from scraps and widely available parts. Tuned to the 40- or 80-meter band, or even down to the 160-meter band, a Hartley or the closely related Tuned-Not-Tuned (TNT) or Tune-Plate-Tuned-Grid (TPTG) continuous-wave (CW) transmitters could put out enough power to work coast-to-coast contacts, or QSOs. Modern hams pay homage to the Depression-era pioneers of amateur radio with regular “QSO Parties” using replica Hartleys – most with bypass capacitors to keep the lethal voltages their forebears had to deal with off the coils.

The Great Depression lasted through the 1930s in America, finally dissipating just before the country mobilized for World War II. With factories suddenly working beyond capacity to supply the war effort, unemployment figures quickly plummeted, and the austere practices of the Depression were generally rolled back. Hobo culture declined and amateur radio was shut down by the federal government for the duration of the war, but neither the war effort nor full employment could kill the hobo spirit — modern hobos still ply the rails to this day. And the skills and mindsets developed by Depression-era social and electronics hackers paved the way for a lot of what was to come in the post-war years.

Embed With Elliot: Debounce Your Noisy Buttons, Part II

If you’ve ever turned a rotary encoder or pushed a cursor button and had it skip a step or two, you’ve suffered directly from button bounce. My old car stereo and my current in-car GPS navigator both have this problem, and it drives me nuts. One button press should be one button press. How hard is that to get right?

In the last session of Embed with Elliot, we looked into exactly how hard it is to get right and concluded that it wasn’t actually all that bad, as long as you’re willing to throw some circuitry at the problem, or accept some sluggishness in software. But engineers cut corners on hardware designs, and parts age and get dirty. Making something as “simple” as a button work with ultra-fast microcontrollers ends up being non-trivial.

And unsurprisingly, for a problem this ubiquitous, there are a myriad of solutions. Some are good, some are bad, and others just have trade-offs. In this installment, we’re going to look at something special: a debouncer that uses minimal resources and is reasonably straightforward in its operation, yet which can debounce along with the best of ’em.

In short, I’ll introduce you to what I think is The Ultimate Debouncer(tm)! And if you don’t agree by the end of this article, I’ll give you your money back.

Continue reading “Embed With Elliot: Debounce Your Noisy Buttons, Part II”

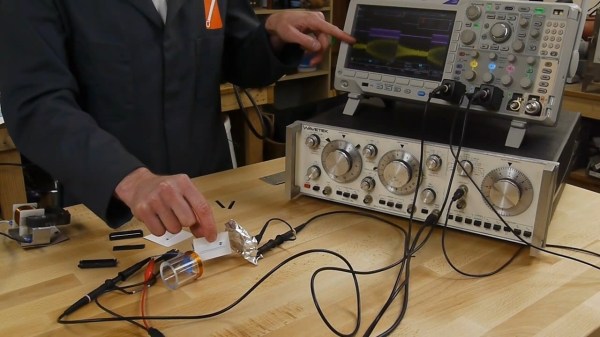

How Store Anti-Theft Alarms Work: Magnetostriction

Now that’s uncanny. Two days before [Ben Krasnow] of the Applied Science YouTube blog posted this video on anti-theft tags that use magnetostriction, we wrote a blog post about a firm that’s using inverse-magnetostriction to generate electricity. Strange synchronicity!

[Ben] takes apart those rectangular plastic security tags that end up embarrassing everyone when the sales people forget to demagnetize them before you leave the store. Inside are two metal strips. One strip gets magnetized and demagnetized, and the other is magnetostrictive — meaning it changes length ever so slightly in the presence of a magnetic field.

A sender coil hits the magnetostrictive strip with a pulsed signal at the strip’s resonant frequency, around 58kHz. The strip expands and contracts along with the sender’s magnetic field. When the sender’s pulse stops, the strip keeps vibrating for a tiny bit of time, emitting an AC magnetic field that’s picked up by the detector. You’re busted.

The final wrinkle is the magnetizable metal strip inside the tag. When it’s not magnetized at all, or magnetized too strongly, the magnetostrictive strip doesn’t respond as much to the sender’s field. When the bias magnet is magnetized just right, the other strip rings like it’s supposed to. Which is why they “demagnetize” the strips at checkout.

We haven’t even spoiled [Ben]’s explanation. He does an amazing job of investigating all of this. He even measures these small strips changing their length by ten parts per million. It’s a great bit of low-tech measurement that ends up being right on the money and deserves the top spot in your “to watch” list.

And now that magenetostriction is in our collective unconscious, what’s the next place we’ll see it pop up?

Continue reading “How Store Anti-Theft Alarms Work: Magnetostriction”

Navigating The Oceans Is Deadly Without A Clock

I came across an interesting question this weekend: how do you establish your East/West location on the globe without modern technology? The answer depends on what you mean by “modern”, it turns out you only have to go back about three centuries to find there was no reliable way. The technology that changed that was a clock; a very special one that kept accurate time despite changing atmospheric conditions and motion. The invention of the Harrison H1 revolutionized maritime travel.

We can thank Andy Weir for getting me onto this topic. I just finished his amazing novel The Martian and I can confirm that George Graves’ opinion of the high quality of that novel is spot on. For the most part, Andy lines up challenges that Mark Watney faces and then engineers a solution around them. But when it came to plotting location on the surface of Mars he made just a passing reference to the need to have accurate clocks to determine longitude. I had always assumed that a sextant was all you needed. But unless you have a known landmark to sight from this will only establish your latitude (North/South position).

Continue reading “Navigating The Oceans Is Deadly Without A Clock”

New Part Day: Time Of Flight Sensors

Every robotics project out there, it seems, needs a way to detect if it’s smashing into a wall repeatedly, acting like the brainless automaton it actually is. The Roomba has wall sensors, just about every robot kit has some way of detecting obstacles its running into, and for ‘wall-following robots’, detecting objects is all they do.

While the earliest of these robots used a piece of wire and a metal contact to act like a switch for these object detectors, ultrasonic sensors – the kind you can buy on eBay for a few bucks – have replaced this clever wire spring switch. Now there’s a new sensor for the same job – the VL6180 – and it measures the speed of light.

The sensors that are used for object and collision detection now use either ultrasonic or infrared light. They’re susceptible to noise, and if you’re doing anything automated, you really don’t want rogue measurements. A time of flight sensor clocks out photons and records how long it takes them to return at 299,792,458 meters per second. It’s less sensitive to noise, and if you can believe this SparkFun demo of this sensor, extremely accurate

This is not the first Time of Flight distance sensor on the market; earlier this week we saw a project use a sensor called the TeraRanger One. This sensor costs €150.00. The VL6180 sensor costs about $6 in quantity one from the usual suspects, and breakout boards with the proper level converters and regulators can be found for about $25. More expensive sensors have a greater range, naturally; the VL6180 is limited to somewhere between 10cm (on paper) and 25cm (in practice). But this is cheap, and it measures the time of flight of pulses of light. That’s just cool.

The Hackaday Prize: The Hacker Behind The First Tricorder

Smartphones are the most common expression of [Gene Roddneberry]’s dream of a small device packed with sensors, but so far, the suite of sensors in the latest and greatest smartphone are only used to tell Uber where to pick you up, or upload pics to an Instagram account. It’s not an ideal situation, but keep in mind the Federation of the 24th century was still transitioning to a post-scarcity economy; we still have about 400 years until angel investors, startups, and accelerators are rendered obsolete.

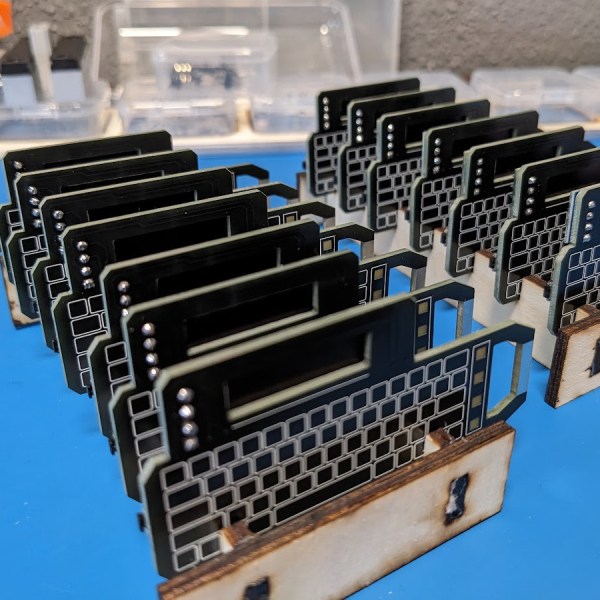

Until then, [Peter Jansen] has dedicated a few years of his life to making the Tricorder of the Star Trek universe a reality. It’s his entry for The Hackaday Prize, and made it to the finals selection, giving [Peter] a one in five chance of winning a trip to space.

[Peter]’s entry, the Open Source Science Tricorder or the Arducorder Mini, is loaded down with sensors. With the right software, it’s able to tell [Peter] the health of leaves, how good the shielding is on [Peter]’s CT scanner, push all the data to the web, and provide a way to sense just about anything happening in the environment. You can check out [Peter]’s video for The Hackaday Prize finals below, and an interview after that.

Continue reading “The Hackaday Prize: The Hacker Behind The First Tricorder”