Our better-traveled colleagues having provided ample coverage of the 34C3 event in Leipzig just after Christmas, it is left to the rest of us to pick over the carcass as though it was the last remnant of a once-magnificent Christmas turkey. There are plenty of talks to sit and watch online, and of course the odd gem that passed the others by.

It probably doesn’t get much worse than nuclear conflagration, when it comes to risks facing the planet. Countries nervously peering at each other, each jealously guarding their stocks of warheads. It seems an unlikely place to find a 34C3 talk about 6502 microprocessors, but that’s what [Moritz Kütt] and [Alex Glaser] managed to deliver.

Policing any peace treaty is a tricky business, and one involving nuclear disarmament is especially so. There is a problem of trust, with so much at stake no party is anxious to reveal all but the most basic information about their arsenals and neither do they trust verification instruments manufactured by a state agency from another player. Thus the instruments used by the inspectors are unable to harvest too much information on what they are inspecting and can only store something analogous to a hash of the data they do acquire, and they must be of a design open enough to be verified. This last point becomes especially difficult when the hardware in question is a modern high-performance microprocessor board, an object of such complexity could easily have been compromised by a nuclear player attempting to game the system.

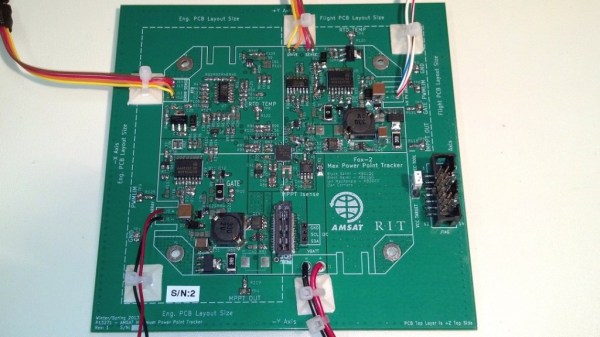

We are taken through the design of a nuclear weapon verification instrument in detail, with some examples and the design problems they highlight. Something as innocuous as an ATtiny microcontroller seeing to the timing of an analogue board takes on a sinister possibility, as it becomes evident that with compromised code it could store unauthorised information or try to fool the inspectors. They show us their first model of detector using a Red Pitaya FPGA board, but make the point that this has a level of complexity that makes it unverifiable.

Then comes the radical idea, if the technology used in this field is too complex for its integrity to be verified, what technology exists at a level that can be verified? Their answer brings us to the 6502, a processor in continuous production for over 40 years and whose internal structures are so well understood as to be de facto in the public domain. In particular they settle upon the Apple II home computer as a 6502 platform, because of its ready availability and the expandability of [Steve Wozniak]’s original design. All parties can both source and inspect the instruments involved.

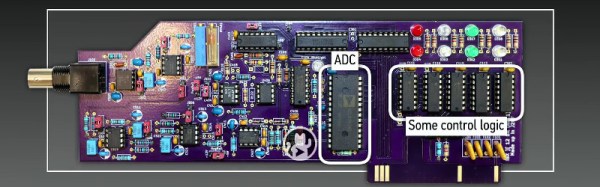

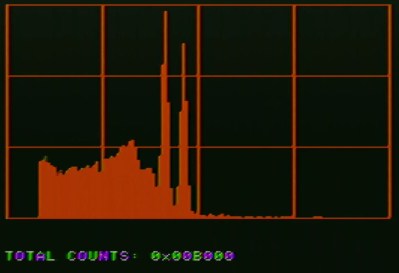

If you’ve never examined a nuclear warhead verification device, the details of the system are fascinating. We’re shown the scintillation detector for measuring the energies present in the incident radiation, and the custom Apple II ADC board which uses only op-amps, an Analog Devices flash ADC chip, and easily verifiable 74-series logic. It’s not intentional but pleasing from a retro computing perspective that everything except perhaps the blue LED indicator could well have been bought for an Apple II peripheral back in the 1980s. They then wrap up the talk with an examination of ways a genuine 6502 system could be made verifiable through non-destructive means.

It is not likely that nuclear inspectors will turn up to the silos with an Apple II in hand, but this does show a solution to some of the problems facing them in their work and might provide pointers towards future instruments. You can read more about their work on their web site.