If you turn over almost any electronic device, you should find all those compliance logos: CE, FCC, UL, TÜV, and friends. They mean that the device meets required standards set by a particular region or testing organisation, and is safe for you, the consumer.

Among those standards are those concerning EMC, or ElectroMagnetic Compatibility. These ensure that the device neither emits RF radiation such that it might interfere with anything in its surroundings, nor is it unusually susceptible to radiation from those surroundings. Achieving a pass in those tests is something of a black art, and it’s one that [Pero] has detailed his exposure to in the process of seeing a large 3-phase power supply through them. It’s a lengthy, and fascinating post.

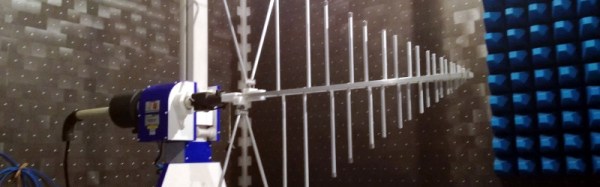

He takes us through a basic though slightly redacted look at the device itself, before describing the testing process, and the EMC lab. These are fascinating places with expert staff who can really help, though they are extremely expensive to book time in. Since the test involves a mains power supply he describes the Line Impedance Stabilisation Network, or LISN, whose job is to safely filter away the RF component on the mains cable, and present a uniform impedance to the device.

In the end his device failed its test, and he was only able to achieve a pass with a bit of that black magic involving the RF compliance engineer’s secret weapons: copper tape and ferrite rings. [Pero] and his colleagues are going to have to redesign their shielding.

We’ve covered our visits to the EMC test lab here before.