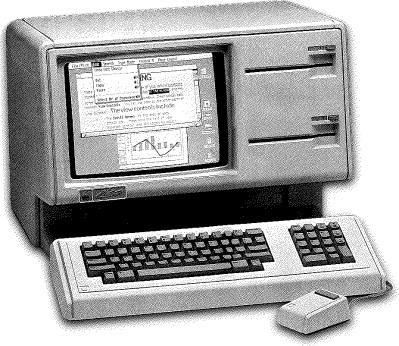

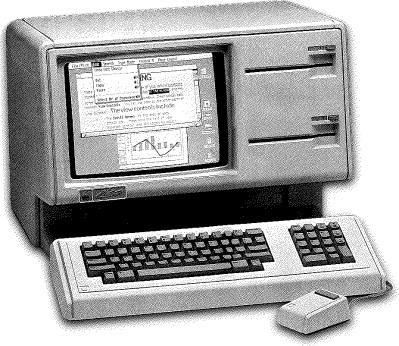

Sure, Apple’s Lisa wasn’t the first computer released with a graphical user interface — Xerox was years ahead with the Alto and the Star workstation — but Lisa was the first that came within the reach of mere mortals. Which doesn’t mean many mortals got their hands on one; with only about 10,000 sold, they were never common, and are vanishingly rare nowadays. Enter [Andrew Yaros], who has graced the world with LisaGUI, an in-browser recreation of the Lisa Office System in Javascript.

Lisa’s GUI varies from modern conventions in a few interesting ways. For one, it is much more document-focused: if you double-click on LisaType, you do not start the program. Instead you “tear off” a document from the “pad” icon of LisaType, which you can then open with another double click. The desktop is also not a folder for files to live permanently, but a temporary space. You can “set aside” a file to the desktop, but its home on disk is unchanged.

Unlike the family of Mac emulators, LisaGUI does not purport to be a perfect replica. [Andrew] has made a few quality-of-life improvements for modern users, as well as a few innovations of his own. For instance, menus are now “sticky”– on the Lisa, you had to hold down the mouse to keep them open, and release on the appropriate entry. LisaGUI leaves the menu open for you to click the entry, as on a later Macintosh.

Unlike the family of Mac emulators, LisaGUI does not purport to be a perfect replica. [Andrew] has made a few quality-of-life improvements for modern users, as well as a few innovations of his own. For instance, menus are now “sticky”– on the Lisa, you had to hold down the mouse to keep them open, and release on the appropriate entry. LisaGUI leaves the menu open for you to click the entry, as on a later Macintosh.

Obviously the menu bar clock and FPS counter are not native to the Lisa; nor is the ability to theme the icons and change (1-bit) colour palettes. The ability to draw unique icons to assign to documents is all [Andrew], but is something we wish we had back in the day. He also makes no attempt to enforce the original aspect ratio, so you’ll be dragging the window to get 4:3 if that’s your jam.

Right now it does not look as though there’s much original software aside from LisaType. We would have loved to see the famous LisaProject, which was the original “killer app” that led NASA to purchase the computer. Still, this is an Alpha and it’s possible more software is to come, if it doesn’t run afoul of Apple’s IP. Certainly we are not looking too hard at this gift horse’s chompers. What’s there is plenty to get a feel for the system, and LisaGUI should be a treat for retrocomputer enthusiasts who aren’t too anal about period-perfect accuracy.

We stumbled across this one in a video from [Action Retro] in which he (the lucky dog) also shows off his Lisa II, the slightly-more-common successor.