We’ve always known, in theory, there are ways to bend wood, but weren’t really clear on how it worked. Now that we’ve seen [Totally Handy]’s recent video, we’ve learned a number of tricks to pull it off. Could we do any of them? Probably not, any more than watching someone solder under a microscope means you could do it yourself with no practice. But it sure made us want to try!

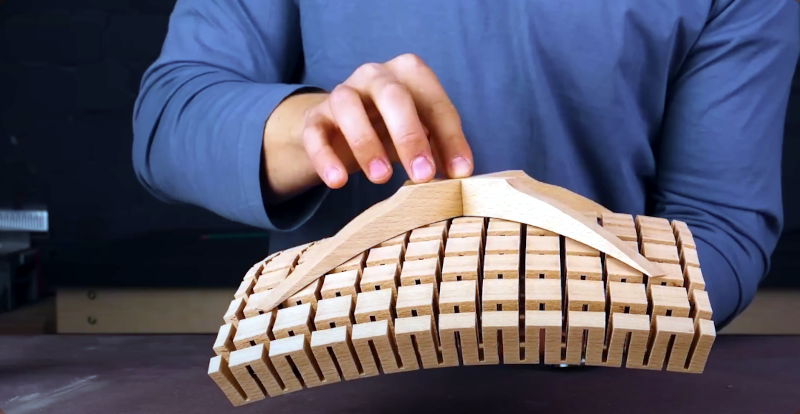

All of the techniques involve either water or steam, but we were fascinated with the cuts that make the wood almost into a flexible mesh. There are several tricks you can pick up, too, if you watch carefully. In “wordless workshop” form, there’s no real audio or text, just watching this guy make some really interesting wood pieces.

It looks like you could do some of this with pretty ordinary tools, although he does use a table saw, a router, and a few types of sanders. There isn’t anything too exotic, although we weren’t entirely clear on how the steam tube worked. If you have a cheap CNC machine, those usually can do a pretty good job on wood, and we wondered if you couldn’t pull off some of these tricks that way, too.

We love projects made with wood that look like they were impossible to make. Don’t forget wood as a construction material. Combined with 3D printing and other techniques, it can make some impressive things.

There is no wood

…only Zuul.

It sure looks like wood to me. Stop the video and look at the end grain in the first project while he is cutting the dados & ploughs in the large block that forms the “bowl”. What is zuul?

Pay no mind. Both are bantering with movie references. One is from “The Matrix” for bending a spoon where you are told that there is no spoon. The second is playing off of the first with a “Ghostbusters” quote. A character is possessed by an evil being called Zuul. When asked if the person is still there Zuul replies that there is no person, only Zuul.

Don’t worry about it, you just stumbled into a pop-culture reference.

🥹🤣🤣🤣

Steam bending is pretty straightforward: All you need is a source of steam and a container large enough to hold your stock. For a pretty simple setup, use a tea kettle and a length of PVC pipe: connect a flexible hose from one end of the pipe to the tea kettle, put the wood in the pipe, and cap the other end. Ideally you want the pipe at a slight angle for drainage, and possibly some internal rack to keep the wood above any condensation.

Let the steam penetrate the wood. Timing depends on how hot the steam is, how large the container is, how big the pieces of wood are, etc, so you check it every so often. When the wood is bendy and flexible, take it out and get it into a form as quickly as possible, then wait for it to cool and dry.

Sites like Fine Woodworking have umpteen articles on steam bending, and there’s a plethora of videos on the subject.

true, but might i add that a better source of steam is a wallpaper steamer. you don’t have to turn that one back on ever minute.

also, bending by kerfing makes for a weak structure because you’re throwing away second moment of inertia to remove stiffness. Laminating and steam bending doesn’t do this, so if you need spars for a boat for instance, this is not the method. if only one principal direction of force exists, lamination gives you the opportunity to make a lighter inner web to make I or H beam structures. while wood has different material properties, engineering remains fundamentally the same in any material.

Or you can tape down the kettle switch, but this does break the kettle after a certain time (and then you have to quickly buy a new one before anyone notices). Happened to a friend bending rockers for a chair…

Also: wooden boat building.

I was thinking specifically canoes.

A few years ago someone wrote about making a canoe, and it landed in the feed. So itgot blogged in a couple of places, including here. Such excitement, and nobody had anything to add.

Spend some time reinforcing that PVC or using something totally different because it sags a LOT when at steam temperatures. I’ve used a PVC bending box and had it slump down so much the cap would no longer cover the end so all the steam blew through. A wooden bending box is traditional, and while it’s a lot more work than the PVC, it sure seems to be more durable.

Though I’ve watched some interesting videos where the people stuck the thing they wanted to bend in boiling water and left it there for a few minutes and then bent with that, and it seemed to work pretty well. I’m going to try that next time.

The people who use ammonia in a sealed setup produce some really interesting stuff. I don’t really understand how that works since it looks to me like it dissolves out the lignin completely so then you have, like, wood dough, but after bending it they let it set and it does seem to hold the new shape, even if it’s tying it in knots.

>it looks to me like it dissolves out the lignin completely

On a quick glance, it seems to me that the ammonia de-polymerizes lignin but does not actually dissolve or remove it. Once the ammonia evaporates away, the lignin polymerizes again and turns stiff.

I’m honestly more impressed that he has integrated his jigs into the final project than the wood bending.

Another technique the video didn’t cover is cold molding with thin veneers. It’s similar to building with fiberglass over a form: you build a form of the shape then cover it with veneer strips. The first layer usually gets tacked down, then the next layer is laid perpendicular to the first and glued down to it. Every subsequent layer is laid perpendicular (or at an angle) to the previous one. Once the final later has dried you remove the form and are left with a custom-built plywood shell in exactly the shape you need.

Ben has you covered:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Z0SsAyHKzc

It looks like we need a saw that cuts a V-shaped kerf.

There are times when a V kerf might help. There are router bits that have a V on the end, but that might not be the right angle or depth. Making a suitable profile router bit might be easier than making a suitable profile saw blade. (I am not a machinist).

If one is just looking for a narrower kerf, a hollow ground blade might work. Not familiar? Most steel blades have “set” – the teeth are alternately bent out so the kerf is wider than the blade body so it does not bind. Carbide blades have the carbide tips wider than the mounting plate, again so the blade does not bind. Most North American circular saw blades of this type cut a 1/8″ kerf. (I don’t know about European or Australian blades). A hollow ground blade is a steel blade that has no set, but the body is ground for most of its cutting depth so the cutting depth is thinner than the rim. The couple of blades like this I have cut a 1/16″ kerf. They also usually have a lot of teeth. Combining a lot of teeth with no set produces an extremely smooth cut.