In-space manufacturing is a big challenge, even with many of the same manufacturing methods being available as on the ground. These methods include rivets, bolts, but also welding, the latter of which was first attempted fifty years ago by Soviet cosmonauts. In-space welding is the subject of a recently announced NASA collaboration. The main aspects to investigate are the effects of reduced gravity and varying amounts of atmosphere on welds.

The Soviets took the lead in space welding when they first performed the feat during the Soyuz-6 mission in 1969. NASA conducted their own welding experiments aboard Skylab in 1973, and in 1984, the first (and last) welds were made in open space during an EVA on the Salyut-7 mission. This time around, NASA wants to investigate fiber laser-based welding, as laid out in these presentation slides. The first set of tests during parabolic flight maneuvers were performed in August of 2024 already, with further testing in space to follow.

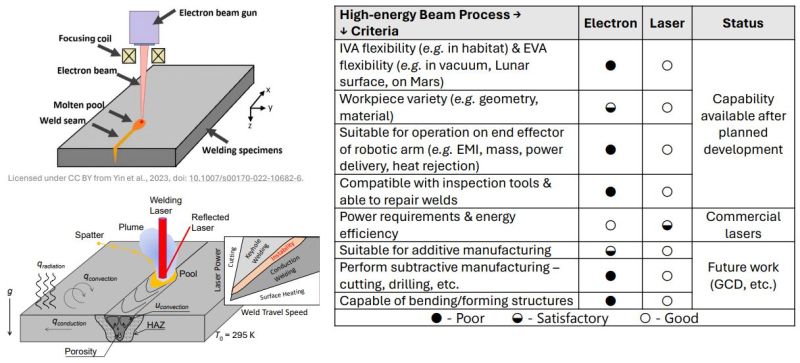

Back in 1996 NASA collaborated with the E.O. Paton Welding Institute in Kyiv, Ukraine, on in-space welding as part of the ISWE project which would have been tested on the Mir space station, but manifesting issues ended up killing this project. Most recently ESA has tested in-space welding using the same electron-beam welding (EBW) approach used by the 1969 Soyuz-6 experiment. Electron beam welding has the advantage of providing great control over the weld in a high-vacuum environment such as found in space.

So why use laser beam welding (LBW) rather than EBW? EBW obviously doesn’t work too well when there is some level of atmosphere, is more limited with materials and has as only major advantage that it uses less power than LBW. As these LBW trials move to space, they may offer new ways to create structure and habitats not only in space, but also on the lunar and Martian surface.

Featured image: comparing laser beam welding with electron beam welding in space. (Source: E. Choi et al., OSU, NASA)

I would be really concerned with spalling. Also, heat dissipation in space is a whole different animal – no air or welding gases to channel heat away… it’s all “black body”, relatively fixed. And although minuscule, the Yarkovsky Effect.

You are acting like they just came up with the idea. You should have more faith in the brilliant minds at NASA.

Talking about the possible challenges isn’t an offense of insufficient “faith”

I bet they haven’t considered any of that, you should probably get on the horn and let them know

Those NASA guys must feel so foolish every time they read an internet comments section.

I wonder why pancake inductive heating coils are not used to just apply enough energy to just melt the two edges. Or would the precision be to low for space applications.

Nice!!!! Handheld Laser Swords!!!

welding in open space, while in earths orbit, will be more or less useless

its the HAZ, heat effected zone, and coming up with viable

processes is unlikely

next is that welding creates vaporized metal, that in a vacume will form a spherical bubble of condensing metal

all over anything in close proximity, joy oh bliss

surface temperatures between the sunlit side of a weldement and the back side are extream

so welding inside giant,very lightly inflated modules is a possible way around some of the problems, and at scale

might prove to be cost effective for tankage and habitat module construction, as most of the engineering requirements for current tanks and habitats are related to

surviving launch, not vacume pressure differential

It’s amazing how many armchair physicists pop up on stories like these ready to tell the experts that they shouldn’t even bother trying.

I mean he sounds like a welder, I’m kind of interested in knowing the challenges from somebody who knows it well

Being a welder doesnt make you an expert in all matters of welding. Guys who know stick have a very different idea of welding than guys who do MIG, and their experience is knowledge is quite different from those who do TIG. Everytime laser welding comes up youll find a pile of guys with 10+ years of experience in every other kind of welding weighing in on how ineffective it is, on how weak it is, etc. Their observations of a youtube video weighed against their experience with THEIR forms of welding leave them confidently wrong in many cases. Some of them have passing experience with YAG laser welding which only leads them to make more unqualified assumptions.

I was guilty of this myself having been raised welding motorcycle frames and sheet metal, then doing laser welding as a jeweler. I spent several years negging Fiber laser videos before attending a trade show and seeing a fiber laser welder in action. They are capable of much deeper penetration with the least significant heat affected zone of any tech Ive seen to date. I wish I could afford a LightWeld or a Miller OptX. Im tempted to take a chance on a chinese system with a raycus laser. You can find those on the bay for 1/10 the price.

In any case, Id trust nasa scientists to have thought things through with far more knowledge and experience than HAD or youtube comment denizens.

Every manufacturing process is uneconomical and produces inferior products until it isn’t and doesn’t any more.

Wait, who said that? Anyways, as we were discussing, steel cannon barrels are a horrible idea, far too brittle, they’ll always just shatter. Let’s invest in another bronze foundry!

So all that electron beam welding that’s done in vacuum chambers (because that’s the only way the e-beam can go much of anywhere) apparently isn’t actually happening, because it can’t be viable. Good to know.

I think the gravity is the issue more than the vacuum.

No punctuation, it’s painful to read this.

Could be handy on the moon, where a little gravity will help to pull down all the tiny metal bits and you have a big heat sink/solar shade underneath you. I wonder if they did any tests on regolith aluminum yet..

Every problem has a solution.

Something not cooling fast enough? Back it with a chiller attached to a massive heatsink array.

Odd shaped puddles due to low gravity?

Spin it up and use acceleration to smash the puddle down. Or use magnets to shape the puddle.

Splatter and sputtering? Electrostatic attraction still works in space.

Spray welding could advance beyond resurfacing metal parts.

Out of atmosphere welding presents unique opportunities.

“EBW obviously doesn’t work too well when there is some level of atmosphere, is more limited with materials and has as only major advantage that it uses less power than LBW.”

Speaking on behalf of an electron beam welding equipment manufacturer and EBW service provider, your claim here is flawed Maya. Although the beginning portion of this statement may ring true about EB welding in atmosphere (vs a high-vacuum EB welding environment); however you quickly forget, despite just talking about it previously- that what they are testing is being welded in space. Meaning no atmosphere and a MUCH deeper vacuum level than what is typically even used for most aerospace, and R&D applications. So that would only benefit the EBW process, not hinder it.

Moving along to the next incorrect statement- laser is NOT a more robust process in terms of materials that can be joined using it. Laser actually has more limitations as far as reflective, and dissimilar material combinations go (commonly used in flight + space applications), and introduces MUCH more heat input into the welded components heat affected zones (HAZ) than EBW. Look up a nail head weld in reference to EBW processing- and see if you can achieve the same thin, deep weld profile (2″ – 6″) in the same materials using a laser system to weld?

Lastly, I can’t speak to the power requirements for a fiber laser welding system- as we do not manufacture those but it’s likely that EB welding actually has a larger power draw than most laser welding systems. EB welding is just a heck of a lot more efficient in translating that power directly into the weld. However these are Scientists; and if the reporter writing this indicated that this R&D laser unit drew more power than a R&D EBW equivalent unit they could be correct. Our legacy company, Hamilton Standard, in the 1960’s developed an R&D EB weld system for NASA for the same purposes and they were able to power it using a special battery source that was located on the spacecraft itself.

They’re discussing whether the process can be applied to both extravehicular work in vacuum and in-habitat work where there would be a normal breathable atmosphere.

In-habitat work seems to me like it would be a very rare need — I would think that fume and fire safety concerns would mean you’d always prefer to work in vacuum regardless of process, and working in atmosphere would only be necessary for repairing part of the habitat that can’t be depressurized.

There are all kinds of tradeoffs between different welding strategies. I am a bit surprised that no one mentioned that any reasonably powered EBW has a high risk of emitting X-Rays when it hits the target material.

That means that shielding from the ionizing radiation needs to be part of the process. Shielding, by its nature, tends to be both heavy and bulky. My guess is that this would rule out using it for EVA welding activities.

Heavy and bulky = expensive when you need to get the equipment out of earths gravity well.

I expect that there will be areas where each technology excels. It will be interesting to see how they will be used.

They also need to add stir welding to the mix of technologies. Blue Origin already uses stir welding for building their rocket bodies, it works great in space or in atmospheres, has very limited safety issues, no reflected light or x rays, and leaves a nice smooth weld. It works with most dissimilar metal combinations (not all), and is a pretty basic to implement.

Stir welding downsides are that it is very hard to use with sharp angles and corners, is probably less energy efficient, and thermal expansion needs to be managed.

I am looking forward to seeing this play out.