Thirty years ago there was a lot of unused spectrum in the 900MHz, 2.4GHz, and 5.2GHz bands. They were licensed for industrial, scientific, and medical uses since their establishment in 1947. But by the 1980s, these bands were identified as being underused. Spectrum is a valuable resource, and in 1985, the FCC first allowed unlicensed, spread spectrum use of these bands. Anyone who has ever configured a router will know the importance of this slice of spectrum: they’re the backbone of WiFi and 4G. If you’re not connected to the Internet through an Ethernet cable, you have the FCC Commissioners and chairpersons in 1985 to thank for that.

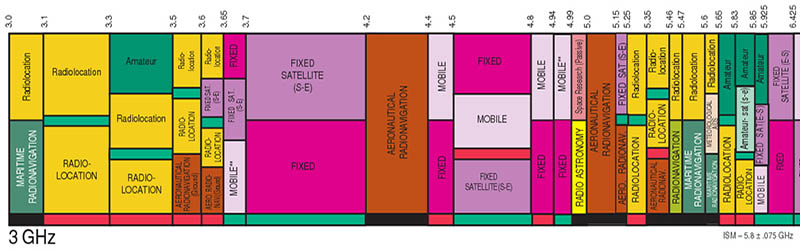

Last week, the FCC unanimously voted to allow the use of spectrum in the 3.5GHz band with the Citizens Broadband Radio Service. This opens up 150 MHz of spectrum from 3550 – 3700MHz for new wireless broadband services. If history repeats itself, you will be connecting to the Internet with the Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) in a few years.

While the April 17th FCC meeting was the formal creation of the CBRS, this is something that has been in the works for a very long time. The band was originally proposed back in 2012 when portions of spectrum were, like the ISM bands back in the 80s, identified as being underused. Right now, the 3.5GHz band is being used for US military radars and aeronautical navigation, but new advances in frequency management as outlined by commissioner [Clyburn] will allow these to coexist with the CBRS. In the words of Chairman [Wheeler], “computer systems can act like spectrum traffic cops.”

Access to the 3.5GHz spectrum will be divided into three levels. The highest tier, incumbent access, will be reserved for the institutions already using it – military radars and aeronautical radio. The second tier, priority access, will be auctioned and licensed by the FCC for broadband providers via Priority Access Licenses (PALs). The final tier, general authorized access, will be available for you and me, provided the spectrum isn’t already allocated to higher tiers. This is an unprecedented development in spectrum allocation and an experiment to see if this type of spectrum allocation leads to more utilization.

There are, however, unanswered questions. Commissioner [O’Rielly] has said the three-year license with no renewable expectancy could limit commercial uptake of PALs. Some commentors have claimed the protocols necessary for the CBRS to coexist with WiFi devices does not exist.

Still, the drumbeat demanding more and more spectrum marches on, and 2/3rds of the 150MHz made available under this order was previously locked up for the exclusive use of the Defense Department. Sharing spectrum between various users is the future, and in this case has the nice bonus of creating a free citizens band radio service.

You can read the full order here, or watch the stream of the April 17th meeting.

2.8GHz!? might want to check your technical accuracy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ISM_band

+1, this I did a double take when I read this

If you have a ham license, you’ve also got access to 3.5-3.7Ghz on a secondary basis.

Gah, that’s 3.3 to 3.5 Ghz

I’m waiting for them to licence the 430–790 THz band.

I’m pretty sure the Sun has exclusive use of that band…

Screw that flaming gas bag, I wanna buy red, I could make a fortune in licence fees on receivers alone!

Sorry, Comcast has lobbied its way into an exclusive license for all markets.

If you’re in the US, an amateur radio license gives you access to that spectrum….

http://www.arrl.org/frequency-allocations

No it doesn’t. As is seen in the illustration at the top of the Hackaday article, and in the ARRL page you pointed to, the Amateur Radio Service 3.5 GHz allocation is below and not a part of the Citizens Broadband Radio Service spectrum.

The 187-page FCC Report & Order does not even mention Amateur Radio, which it would do if the FCC were creating a multibillion-dollar new venture on top of ham radio.

An amateur radio license does not give you access to that spectrum. The Amateur Radio Service shared band is below and not a part of the Citizens Broadband Radio Service spectrum.

The 187-page FCC Report & Order does not even mention Amateur Radio. I’d think it would, if the FCC created this new, potentially multibillion-dollar communications infrastructure on top of ham radio.

The confusion may be in calling this the “3.5 GHz band”, when the CBRS starts at 3.55 GHz.

I’m still digesting the Report & Order. I am concerned, however, that lobbying may sooner or later defeat the general access provisions and close off direct citizen access to the band.

Just curious: What frequencies are used by automotive radar, like Subaru’s? Are they licensed? Does each car maker get their own frequency, or do they have to all co-exist? What happens when a Mercedes and a Subaru meet in a dark alley? Do they each think the other’s transmission is its own echo?

Also, are we on our own for this, or will someone make modules for 3550-3700 MHz that we can use in our projects?

“What happens when a Mercedes and a Subaru meet in a dark alley?”

9 months later they’ve got a brood of Smart cars.

That just made my day, thanks

The FCC issued a notice of proposed rulemaking saying that they wanted to take away the secondary ham allocation at 76-81 GHz and turn it over to automotive radars, though the way they worded it makes it look like the radars themselves would be at 77-81, and the incumbent primary users at 76-77 would no longer have to share with the hams. The ARRL is, of course, opposing this.

As an aside – if anyone out there is a ham and has operated on 76-81 GHz, I’d love to hear from you.

I have no idea how the automotive radars work, but I would suspect they use Gunn Diodes. If so, their emissions would be very, very noisily broadband, so specific frequency assignments wouldn’t work. I could imagine them pulse coding their VIN, for instance, and autocorrelating to recover just those returns. But that is pure speculation.

As far as modules… well, eventually. :-)

Most automotive radars use a CMOS oscillator and multiplier stages. Modern IC processes are good enough to allow making that.

Not Gunn diodes anymore. Some are direct 76GHz oscillators and mixers, but most use harmonic mixers and multipliers and the powerlevels are VERY low.

Gunn diodes do not allow one to do modern tricks like beamforming frequency hopping as easily as modern tranceivers. Hittite and TriQuint make integrated transeivers along with Infineon for that band.

Some cars also have 24GHz rarads as that “low” things are easier than at 76GHz, butthey get to share the spectrum with hams, door openers, speed radars and telecom stuff lie ubiquiti airfiber.

I’m pretty sure that the Subaru uses cameras and not radar. I have a 2015 Forester with eyesight and its a god send for traffic around here.

I thought sharing was communism :P

It depends on who gets how much share.

I’m happy to see that the FCC is becoming more interested in allowing the general public access to more bands. I hope that good things will come from this.

However, if this works anything like the amateur radio allocations in that neck of the spectrum, we’ll have to borrow tech from commercial communications equipment and hack it to work for us.

Agreed, only relatively recently have I seen a “common” commercially-made transceiver that handles 1.2GHz natively… anything higher requires a downconverter to be acquired or made.

AFIK, there have been a few over the years that could do 1.2GHz, but most of them were radios that came in pieces. In other words, you could have 1.2GHz, if you wanted to spend a significant chunk more for the 1.2GHz module.

Heck, even 900MHz is tough to get into. The only 900 MHz radios I’ve seen are converted commercial handhelds.

I would love to see radios come out in the near future that, because they would be SDR-based, could be programmed to be used on whichever band you want, within the limit of the SDR’s chips (I’ve seen them go as high as 6GHz, and as low as a few hunded KHz). I think that such a transceiver could do a heck of a lot more than our current crop of somewhat limited ham radios.

1.2GHz radios were kind of a “small production run” kind of thing… sell them for a couple years and then wait another decade. Keep an eye open for used Icom IC-Delta1 (or IC-Delta-1E) HTs. Maybe an IC-Delta100 mobile (ten watts!). Yaesu made an HT, the FT-911. These turn up used once in a while. Icom also had the T81A, which was kind of trouble prone. I’m not a big Icom fan, but I’ve got to say the IC-Delta1A is a really good looking radio.

In new radios, the Alinco DJ-G7 goes up to 1.2GHz. For 900MHz, there’s was the Alinco DJ-29T, but it looks like they’re already done making those. Maybe a used one?

I have a rather old Standard C568. 2M, 440, and 1.2, but it only makes 35mW on 1.2 GHz. I use it to crossband to a Kenwood D700 in the car. 1.2GHz will go through a commercial building (lots of rebar and metallized glass) when 2M and even 440 won’t make it, but even the slightest bit of foliage will stop it cold. Or, as they say, “If you can see ’em, you can work ’em!”

I guess it goes through the ‘holes’ (from an EM viewpoint) of those buildings but foliage overlaps?

Donät forget the Kenwood TH-55 1.2GHz handheld!

But yeah, the common way of getting on 1.2GHz is buying or building a transverter (like from kuhne).

There’s also IC-910 and IC-1275 multimodes for 1.2GHz.

Modifying surplus 900MHz cellular phones to 1.2GHz is sometimes done here. It is nowhere as popular as modifying old 450MHz gear to the 434MHz hamband, but modification tutorials and info does exist, along with proper firmware images for the radios :)

I dunno about the hacking part. All CBRS operations have to be connected, directly or indirectly, to the Spectrum Access Systems (SAS) administrators. There continues to be speculation about how many of these providers there will be and how much detailed information the SAS will collect about private individuals using the CBRS, but it seems certain that your devices will have to obey the SAS to get access.

AT&T opposed allowing the general public in, or at least argued they should be phased in later and slowly. For its part, however, the FCC used the word “immediate” several times – in that general public should be allowed in immediately (when the whole system is set up and operating to the FCC’s satisfaction).

They always talk about the bands being so crowded, but when I use SDR to nose around I see lots of empty space. Although maybe it depends on where you are? Does any of you live in let’s say NYC and use SDR? Is it really so crowded?

SDR allows for much more efficient use of spectrum that traditional receivers. The filters are much much better at discriminating between two signals close together. So you don’t need huge spaces between stations. Also oscillators have gotten way more precise and that also decreases the need for large spaces between channels/stations.

Unfortunately the laws were written long before technology has gotten to this point and there is still a lot of old equipment still in use.

There is also lots of squatting going on. People holding licences because they may need it in the future or because they always had it.

Lots of spectrum is just reserved for that one time a year its need in a particular area. Aircraft flying over a particular area for example.

Then there is propagation variable. During some weather conditions signals can travel well beyond the line of sight. So to make sure the frequency is always available frequencies must be licensed over huge geographic areas.

All kinds of reasons why things are this way and most of it is legacy. Its a very difficult thing to fix.

In the US the FCC is doing a narrowbanding mandate with commercial radio users. At first it was a move from 2KHz channels to 12.5kHz and the next one is the transfer to 6.25kHz channels.

Btw SDR’s are not a magic bullet, to do those reall narrow filters ou need to throw more cpu power at the problem, when with analog radios ou could use a 20cent filter. Analog radios are currently also cheaper.

Nice! But right now I’m more interested in 160-190 kHz. :)

good to see other bands opening up, honey bees don’t like us using 900MHz (nature reserved that wavelength first). but then again its only our food supply.