In the last Hacking and Kids post, I talked about an activity you can do with kids when you don’t have a lot of time or resources. The key idea was to have fun and learn a little bit about open and closed loop control. One of the things I usually briefly mention when I do that is the idea of a design trade: Why, for example, a robot might use wheels instead of legs, or treads instead of wheels.

Engineers and makers perform trades like this all the time. Suppose you are building a data logging system. You want precise samples, large storage capacity, and many channels. But you also want a low cost and low power drain. You might also want high reliability. All of these requirements will lead to different trades. A hard drive would provide a lot of space, but is more expensive, less reliable, larger, and more power hungry than, say, an SD card. So there isn’t a right choice. It depends on which of the factors are most important for this particular design. A data logger in a well-powered rack might be well served to have a terrabyte hard drive, while a battery powered logger in a matchbox that will be up on the side of a mountain might be better off with an SD card.

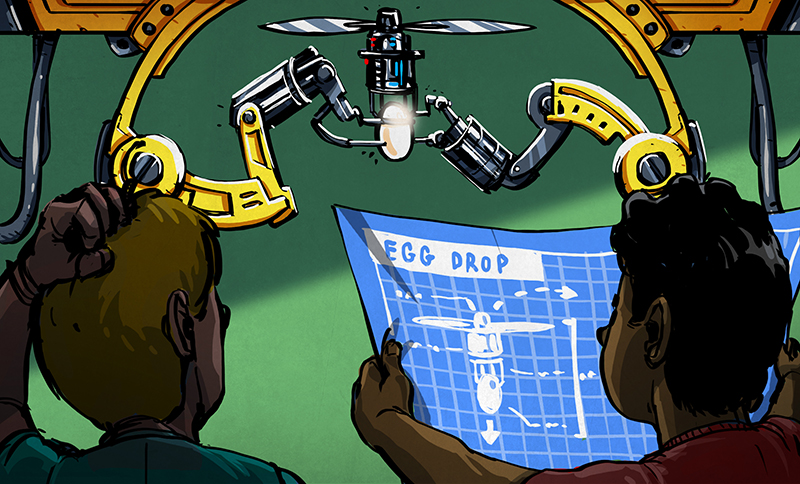

We can all relate to that example, but it is pretty boring to a kid. You probably can’t get them to design a data logger, anyway. But if I have about an hour and a little prep time, I have a different way to get the same point across. It is a modified version of the classic “egg drop”, but it is simple enough to do in an hour with very little preparation time.

Here’s how it works: I have a step stool or something that will safely hold my weight in front of the class. I climb up on it with an egg in a baggie and I drop the egg. So far, that always results in a messy broken egg (inside the baggie, hopefully). Now I have their attention.

I tell them that the egg is an astronaut and when the space ship she’s in lands, we don’t want her cracked up like Humpty Dumpty. I split up the kids into a few teams (with reasonably even distributions of ages, if they are a mixed group) and I show them that I have lots of materials in yet more baggies. Exactly what I have will depend on what I had on hand. I might have marshmallows, flour, cereal, sand, cut up sponges, newspapers, or packing peanuts. I’ll also have some basic supplies like tape, scissors, and markers. There’s also a scale.

Each team picks a name and decides how they want to protect their egg. Here’s the catch: each bag of materials has a cost. I will tell the kids that we will have a prize for the lowest cost solution and the lightest solution (as long as they, of course, don’t break the egg). I assign costs based on my judgement of how lightweight the material is along with how well I think it will cushion. So marshmallows and cereal are expensive. Sand is less expensive. I try to make them struggle to get both light and cheap in the same design.

Most of the kids will pack things around the egg inside the baggie. Younger team members can have the job of decorating the egg. I’ve seen kids make parachutes out of newspaper and secure them with duct tape. You never know just how creative the kids will get.

This is, of course, not an original idea — egg drops have been going on in one form or another for a long time. However, by using the premade baggies it is quick to set up and quick to do. Using the baggie for structure prevents a mess and also saves time from having to build a box or get a suitable box for each team. But the key point is the use of minimal weight and cost and how it feeds the design trades they must make. You can show them how they make trades like this all the time in everyday life, from which route to take home to how to spend their allowance.

But it is also undeniable fun. When they shout out 3…2…1… before you drop their egg, you can feel the excitement. The suspense when you open the baggie to see if the egg survived is palpable. The fun keeps them interested and it will help them remember the lessons you teach them. For a quick run of it, you can set a maximum weight and continue dropping things from the step stool. If you have time, you can try dropping them out of a window and get a little more impact. Some eggs will break. I always remind the kids that you often learn more from a failure than from a success.

As engineers or makers or designers or whatever label you apply to yourself, it is tempting to go overboard on something like this. We could build test fixtures with instruments. A shock absorber design immediately comes to mind. Resist that. Keep it simple and save those ideas for long term science projects. A simple activity like this will let you share your love of creation with a large group and maybe start a kid on the road to being a hacker like you.

By the way, if you need some help on figuring out what might work well, [Mark Rober] has a pretty entertaining analysis of what makes egg drop capsules successful in the video below (and he should know since he worked on the Curiosity rover).

This is AWESOME!!!! #STEMLove!

Just excellent.

“Which way you go depends on where you’re going.” Who knew?

-dlj.

My kid’s school did the egg drop contest, but with a twist. The winner was determined by (1) the least damage to the egg after 2 drops, and (2) the lowest cost of the solution from a set inventory of items (Styrofoam, string, newspaper, tape, plastic, etc). Most kids went with the parachute/helicopter approach. A few spent a little more “money” and incorporated a shock absorbing system as well. The winning solution, though, was a team that just wrapped the bejesus out of the egg in the cheapest material they could get (the newspaper) and tossed it over the side without any velocity retardation at all.

Asheets,

As long as you’re clear about who was picking the winner: the winner was determined by whoever set the proportion of criterion one to criterion two in adding up the score. Check these two kids:

Damage Cost

Annie 2 3

Ellie 1 4

Now these two teachers

Damage Cost

Grizelda x2 x1

Horribila x1 x2

“Winners”

Grizelda sez “Annie scored 2×2 + 3×1, total 7 but Ellie got 2×1 + 1×4 = 6, so Annie wins.”

Horribila sex “You’re crazy, Annie scored a lousy 8 and Ellie got 9, so Ellie wins.”

The moral is not that the accountant will always screw the engineers; it’s that you cannot serve two masters.

Cheers,

-dlj.

I was one of the judges. The paper was cheapest by far, and the egg was undamaged.

I assume you’re saying the outside of the egg was undamaged.

If a chicken were the judge they might think more highly of a system which allowed the shell to break, absorbing some of the shock which might otherwise be transmitted to the poor embryo…

You may have that rare case in which there is a clear winner on all conceivable criteria. In that case, the problem doesn’t arise. Such cases are, however, incredibly rare in the real world. The ability of humans to deceive ourselves about the fairness and comprehensivity of our human-made systems seems to me virtually limitless.

Cheers,

-dlj.

Hah, this gave me a flashback to my 5th or 6th grade SECME competition. Eggdrop was one of the events I competed in (as well as programming, but that was…). My friend and I came up with a Styrofoam ball about 8″ in diameter from a solar system model kit, split it in half, hollowed it out some, and used marshmallows for padding the egg (hey man, don’t judge). I think I got the idea from bicycle helmets. We spent about 30 minutes on it after getting the supplies and never tested it.

We felt like total idiots when we showed up at UCF and other kids had all of these elaborate inflatable contraptions and wooden frames. I don’t think I saw any drinking straw frames like this. The test was a two story drop followed by a three story drop in an atrium, and the winner was the one who had the smallest volume contraption, followed by lowest weight (maybe the other way around, I can’t remember).

Ours was the only survivor for the three story drop. The inflatable ones wobbled around and landed heavy side down and the rigid structures were all either too rigid or not rigid enough. Turns out Styrofoam does a great job of being a minor airbrake and a shock absorber. It got a little flattened after each drop, but it kept working.

I felt kind of bad at the time, because we obviously spent a lot less effort on it than virtually everyone else, but I guess it was a good lesson that physics doesn’t care how hard you try, just whether or not it will work.

This is why we need to encourage science in kids. I volunteer with Cub scouts and have a limited budget to get things done, so we often have to be creative. The solutions people have come up for things are amazing (and I have learned to look at options before trying to come up with my own over-complicated solution:

This week we were talking about forensics. I didn’t want to make a mess with ink and didn’t have a pad on hand, so instead of purchasing ink, we used my phone with a stick on macro lens to photograph the fingerprint patterns (also gave the kids more options to participate by using a bluetooth remote shutter). We also had to do footprints, and I was given a suggestion:

-Spray the bottom of their shoe with cooling spray and have them step on a piece of paper (them wiped the rest off the shoe)

-Use baking cocoa dabbed on the paper with a brush like a fingerprinting kit. Once you dump the extra, the footprints is revealed in an environmentally friendly way (NOTE baking cocoa is not sweetened. The kids of course tried to lick it). Beats the heck out of plaster casting in mud.

Again, this allowed multiple kids to participate in both making the print and “dusting” for it. Then of course, you can have others try and match up the prints to an individual to teach how people investigate (they all though it was unfair when the “investigators” wanted to look at the bottom of their shoes for some reason).

The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado, each year has an egg drop contest pitting their scientists and engineers, and administrative assistants against the 6th grade class of a local elementary school.

Fun is had by all.

This page features “Godzillegg”, an entry I had a hand in building.

http://www.ucar.edu/communications/staffnotes/9807/egg.html

Another great article on kids + science… thanks, Al, keep up the excellent work!

Cheers

Very little of the evolution described herein is science. This is the domain of engineering. And failure cannot always be good in engineering as you will only learn what does not work, but still have no solution to the problem at hand.

Failure is valuable in science. Much is learned from scientific failures; and well-done science failures can contribute as much value as a supposed ‘success’.

a failure in engineering is only as helpful as how well it is documented. The more documentation and logging you have of what was happening the more you can learn from a failure. If the only conclusion you can make is “it blew up” then you can’t learn a lot. If the conclusion is “a strut inside the LOX tanked of the second stage failed after 139 seconds after launch” then you can learn a lot.

Had this discussion with school chum working at JPL. Engineering, as we all know, is about cost-effective solutions using well-documented physical properties. Experiments are not performed on your design, but the design is subject to the rigors of testing to generate a statistically-valid body of data.

That is why they are rocket scientists, and not really rocket engineers. But have seen engineers do good science, and have seen scientists do good engineering. But try to not get the title and the activity mixed up.

You pretty much already said it, but engineering is the application of known science to perform a task with a predicted outcome and science is the application of engineering to test an unknown. The tautology of my definition is intentional. Some people prefer to limit science to those occasions were fundamental unknowns are tested only.

While training differs in what aspects are stressed (or not, depending on the fields in question), the difference is largely defined by activity and is relatively arbitrary, especially in academics. I know mechanical engineers doing fundamental plasma physics research, and physicists by training doing data logging and interpretation for racing teams. What is biological research? Is it reverse engineering, because we are studying natural technology* (we know all of the fundamental underlying physics of importance), or is it science, because we are so far away from understanding all of it completely and cannot make very significant predictions?

Although… “rocket scientists” are absolutely engineers in practice (and in job title). Rocket scientist does sound cooler, though, than propulsion engineer or payload engineer.

*Yes, I’m aware of the implication of the word “technology” when applied to something naturally occurring. I don’t mean it that way.

Drop the egg inside the chicken… ( I heard at least one competition the kids actually won with it)

As God as my witness, I thought turkeys could fly….

That episode probably cam out before most of the readership of this site was born!

Was just discussing this with a customer a couple of days ago. Haven’t thought about that episode in years, and now twice in a week!

This reminds me of the egg drop we had when I was in 6th grade. I was heavily into airplanes at the time, so my idea was to put the egg on top of a pair of short cardboard wings (we were limited to specific dimensions). In my young, unlearned mind I pictured my egg drop vehicle soaring through the heavens and coming to a perfect landing amid the cheers of my classmates. What actually happened was that it immediately flipped over and landed heavily directly on the egg. Oops. Lesson learned.

Nice video. My fontan patients would argue with some of the subscription criteria though.

My Introduction to Engineering class in college put an interesting twist on the egg drop challenge by requiring that we build a device to stop a free-falling egg. The scoring system was based on the ratio of height dropped to mass used in the device. The biggest problem was targeting since the wind kept blowing eggs off course; if my team hadn’t missed our first drop, we would have won.

egg in condom

fill with custard

I did this in 5th grade or so, 2.5 stories up. My parachute was a garbage bag, which failed horribly. But the actual egg vehicle was a paper box with the egg supported in the middle by 3 short pieces of panty hose. Tie knot at end, insert into box, tie knot below middle, place in egg, tie knot on top of egg, run through edge of box and tie* to finish that strand. Well, postpone that last tie off till after you run support 1 through supports 2 and 3. Why 3? I would have done 2 in just horizontal directions if I could have gotten the parachute to work reliably, but the vertical support kept things stable in case everything landed on corners.

I know I survived the drop, but I might not have been the smallest/cheapest/whatever the judging was on. But I did survive more than one drop.