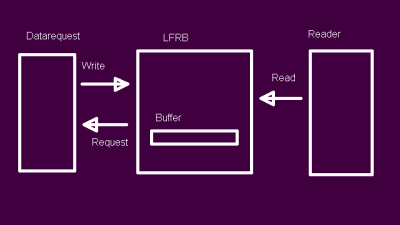

In the previous article we looked at designing a lock-free ring buffer (LFRB) in Ada, contrasting and comparing it with the C++-based version which it is based on, and highlighting the Ada way of doing things. In this article we’ll cover implementing the LFRB, including the data request task that the LFRB will be using to fill the buffer with. Accompanying the LFRB is a test driver, which will allow us to not only demonstrate the usage of the LFRB, but also to verify the correctness of the code.

This test driver is uncomplicated: in the main task it sets up the LFRB with a 20 byte buffer, after which it begins to read 8 byte sections. This will trigger the LFRB to begin requesting data from the data request task, with this data request task setting an end-of-file (EoF) state after writing 100 bytes. The main task will keep reading 8-byte chunks until the LFRB is empty. It will also compare the read byte values with the expected value, being the value range of 0 to 99.

Test Driver

The Ada version of the test driver for the LFRB can be found in the same GitHub project as the C++ version. The file is called test_databuffer.adb and can be found in the ada/reference/ folder. The Makefile to build the reference project is found in the /ada folder, which requires an Ada toolchain to be installed as well as Make. For details on this aspect, see the first article in this series. When running make in the folder, the build files are placed under obj/ and the resulting binary under bin/.

The LFRB package is called LFRingDataBuffer, which we include along with the dataRequest package that contains the data request task. Obviously, since typing out LFRingDataBuffer over and over would be tiresome, we rename the package:

with LFRingDataBuffer;

with dataRequest; use dataRequest;

procedure test_databuffer is

package DB renames LFRingDataBuffer;

[..]

After this we can initialize the LFRB:

initret : Boolean;

[..]

initret := DB.init(20);

if initret = False then

put_line("DB Init failed.");

return;

end if;

Before we start reading from the LFRB, we create the data request task:

drq : DB.drq_access; [..] drq := new dataRequestTask; DB.setDataRequestTask(drq);

This creates a reference to a dataRequestTask instance, which is found in the dataRequest package. We pass this reference to the LFRB so that it can call entries on it, as we will see in a moment.

After this we can start reading data from the LFRB in a while loop:

bytes : DB.buff_array (0..7);

read : Unsigned_32;

emptied : Boolean;

[..]

emptied := False;

while emptied = False loop

read := DB.read(8, bytes);

[..]

if DB.isEoF then

emptied := DB.isEmpty;

end if;

end loop;

As we know what the value of each byte we read has to be, we can validate it and also print it out to give the user something to look at:

idx : Unsigned_32 := 0;

[..]

idx := 0;

for i in 0 .. Integer(read - 1) loop

put(Unsigned_8'Image(bytes(idx)) & " ");

if expected /= bytes(idx) then

aborted := True;

end if;

idx:= idx + 1;

expected := expected + 1;

end loop;

Of note here is that put() from the Ada.Text_IO package is similar to the put_line() procedure except that it doesn’t add a newline. We also see here how to get the string representation of an integer variable, using the 'Image attribute. For Ada 2012 we can use it in this fashion, though since 2016 and in Ada 2022 we can also use it directly on a variable, e.g.:

put(bytes(idx)'Image & " ");

Finally, we end the loop by checking both whether EoF is set and whether the buffer is empty:

if DB.isEoF then

emptied := DB.isEmpty;

end if;

With the test driver in place, we can finally look at the LFRB implementation.

Initialization

Moving on to the LFRB’s implementation file (lfringdatabuffer.adb), we can in the init procedure see a number of items which we covered in the previous article already, specifically the buffer type and its allocation, as well as the unchecked deallocation procedure. All of the relevant variables are set to their appropriate value, which is zero except for the number of free bytes (since the buffer is empty) and the last index (capacity – 1).

Flags like EoF (False) are also set to their starting value. If we call init with an existing buffer we first delete it before creating a new one with the requested capacity.

Reading

Moving our attention to the read function, we know that the buffer is still empty, so nothing can be read from the buffer. This means that the first thing we have to do is request more data to fill the buffer with. This is the first check in the read function:

if eof = false and len > unread then

put_line("Requesting data...");

requestData;

end if;

Here len is the requested number of bytes that we intend to read, with unread being the number of unread bytes in the buffer. Since len will always be more than zero (unless you are trying to read zero bytes, of course…), this means that we will call the requestData procedure. Since it has no parameters we omit the parentheses.

This procedure calls an entry on the data request task before waiting for data to arrive:

dataRequestPending := True;

readT.fetch;

while dataRequestPending = True loop

delay 0.1; -- delay 100 ms.

end loop;

We set the atomic variable dataRequestPending which will be toggled upon a write action, before calling the fetch entry on the data request task reference which got passed in from the test driver earlier. After this we loop with a 100 ms wait until the data has arrived. Depending on the context, having a time-out here might be desirable.

We can now finally look at the data request task. This is found in the reference folder, with the specification (dataRequest.ads) giving a good idea of what the Ada rendezvous synchronization mechanism looks like:

package dataRequest is task type dataRequestTask is entry fetch; end dataRequestTask; end dataRequest;

Unlike an Ada task, which is auto-started with the master task to which the subtask belongs, a task type can be instantiated and started at will. To communicate with the task we use the rendezvous mechanism, which presents an interface (entries) to other tasks that are effectively like procedures, including the passing of parameters. Here we have defined just one entry called fetch, for hopefully obvious reasons.

The task body is found in dataRequest.adb, which demonstrates the rendezvous select loop:

task body dataRequestTask is

[..]

begin

loop

select

accept fetch do

[..]

end fetch;

or

terminate;

end select;

end loop;

end dataRequestTask;

To make sure that the task doesn’t just exit after handling one call, we use a loop around the select block. By using or we can handle more than one call, with each entry handler (accept) getting its own section so that we can theoretically handle an infinite number of entries with one task. Since we only have one entry this may seem redundant, but to make sure that the task does exit when the application terminates we add an or block with the terminate keyword.

With this structure in place we got a basic rendezvous-enabled task that can handle fetch calls from the LFRB and write into the buffer. Summarized this looks like the following:

data : DB.buff_array (0..9);

wrote : Unsigned_32;

[..]

wrote := DB.write(data);

put_line("Wrote " & Unsigned_32'Image(wrote) & HT & "- ");

Here we can also see the way that special ASCII characters are handled in Ada’s Text_IO procedures, using the Ada.Characters.Latin_1 package. In this case we concatenate the horizontal tab (HT) character.

Skipping ahead a bit to where the data is now written into the LFRB’s buffer, we can read it by first checking how many bytes can be read until the end of the buffer (comparing the read index with the buffer end index). This can result in a number of of outcomes: either we can read everything in one go, or we may need to read part from the front of the buffer, or we have fewer bytes left unread than requested. These states should be fairly obvious so I won’t cover them here in detail, but feel free to put in a request.

To take the basic example of reading all of the requested bytes in a single chunk, we have to read the relevant indices of the buffer into the bytes array that was passed as a bidirectional parameter to the read function:

function read(len: Unsigned_32; bytes: in out buff_array) return Unsigned_32 is

This is done with a single copy action and an array slice on the (dereferenced) buffer array:

readback := (read_index + len) - 1; bytes := buffer.all(read_index .. readback);

We’re copying into the entire range of the target array, so no slice is necessary here. On the buffer array, we start at the first unread byte (read_index), with that index plus the number of bytes we intend to read as the last byte. Minus one due to us starting the array with zero instead of 1. This would be a handy optimization, but since we’re a stickler for tradition, this is what we have to live with.

Writing

Writing into the buffer is easier than reading, as we only have to concern ourselves with the data that is in the buffer. Even so it is quite similar, just with a focus on free bytes rather than unread ones. Hence we start with looking at how many bytes we can write:

locfree : Unsigned_32;

bytesSingleWrite: Unsigned_32;

[..]

locfree := free;

bytesSingleWrite := free;

if (buff_last - data_back) < bytesSingleWrite then

bytesSingleWrite := buff_last - data_back + 1;

end if;

We then have to test for the different scenarios, same as with reading. For example with a straight write:

if data'Length <= bytesSingleWrite then

writeback := (data_back + data'Length) - 1;

buffer.all(data_back .. writeback) := data;

elsif

[..]

end if;

Of note here is that we can obtain the size of a regular array with the 'Length attribute. Since we can write the whole chunk in one go, we set the slice on the target (the dereferenced buffer) from the write index (data_back) to (and including) the size of the data we’re writing (minus one, because tradition). If we have to do partial copying of the data we need to use array slices here as well, but here it is only needed on the buffer.

Finally, we have two more items to take care of in the write function. The first is letting the data request procedure know that data has arrived by setting dataRequestPending to false. The other is to check whether we can request more data if there is space in the buffer:

if eof = true then

null;

elsif free > 204799 then

readT.fetch;

end if;

There are a few notable things in this code. The first is that Ada does not allow you to have empty blocks, but requires you to mark those with null. The other is that magic numbers can be problematic. Originally the fixed data request block size in NymphCast was 200 kB before it became configurable. If we were to change the magic number here to e.g. 10 (bytes), we’d call the fetch entry on the data request task again on the first read request, getting us a full buffer.

EoF

With all of the preceding, we now have a functioning, lock-free ring buffer in Ada. Obviously we have only touched on the core parts of what makes it tick, and skimmed over the variables involved in keeping track of where what is going and where it should not be, not to mention how much. Much of this should be easily pieced together from the linked source files, but can be expanded upon, if desired.

Although we have a basic LFRB now, the observing among us may have noticed that most of the functions and procedures in the Ada version of the LFRB as located on GitHub are currently stubs, and that the C++ version does a lot more. Much of this functionality involves seeking in the buffer and a number of other tasks that make a lot of sense when combined with a media player like in NymphCast. These features will continue to be added over time as the LFRB project finds more use, but probably aren’t very interesting to cover.

Feel free to sound off in the comments on what more you may want to see involving the LFRB.

Market share: Ada 1.08%.

https://www.google.com/search?q=percent+of+programmers+using+ada%3F&sca_esv=de3e428f524f6eaa&sca_upv=1&rlz=1C1QCTP_enUS1084US1084&sxsrf=ADLYWIKIO8UT_1lklAWTuqlbzaY0CHg-Iw%3A1722529278572&ei=_rWrZtHUIp-f0PEP_9mI-Qk&ved=0ahUKEwjRy47OmdSHAxWfDzQIHf8sIp8Q4dUDCBA&oq=percent+of+programmers+using+ada%3F&gs_lp=Egxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAiIXBlcmNlbnQgb2YgcHJvZ3JhbW1lcnMgdXNpbmcgYWRhPzIIECEYoAEYwwQyCBAhGKABGMMESNo5UIMfWIMfcAF4AJABAJgBgAGgAc0BqgEDMS4xuAEMyAEA-AEBmAICoAKJAcICChAAGLADGNYEGEeYAwCIBgGQBgiSBwMxLjGgB9gK&sclient=gws-wiz-serp

Better: https://www.google.com/search?q=percent+of+programmers+using+ada

“[…] chart created by analyzing raw data that comes from the Google search engine on how often programming language tutorials are searched.”

I wonder what the correlation is between actual use in “real” development and searching for help on a particular language.

For example, do the C# or C++ deeply entrenched developers conduct as many searches as people (like me more recently) playing with/learning Python?

When I’ve been full time, head down working in a language all day every day (C, C#, VB(x), ASP, ASP.NET), I think I had more committed to memory. Now that I only do small utility projects as a small, completely discretionary facet of my job (mostly in Python), I’m just as likely to do a search as I am to rely on my memory and just test to see what happens.

On the other hand, my memory might have worked better in my 20’s 30’s than it does now. On yet another hand, maybe the internet has just made my brain lazy.

Yep, I’m so old that I used to have to learn/reference a language from bound, paper manuals or CD’s. On the plus side(?) if the internet goes away, and VB4 comes back, I’m set. You’ll all be paging me to get me to look stuff up for you.

“Market share: Ada 1.08%.”

You might want to do some research into *where* that market share is coming from to realize why someone might want to learn Ada.

Sometimes you have a choice as to what language to use. Many times you don’t.

Get good a COBOL!

Ha Ha!

I knew some COBOL guys who made a lot of money off it because most programmers refused to use it.

And how is it even relevant?

Market share means absolutely nothing.

Ada > Rust, but gee back to pascal?

Wouldn’t that be fun. I do miss my Turbo Pascal days :) . Glad we still have Lazarus/Free Pascal to work with if desired :) . Most of my work is Python and C/C++ .. but still enjoy dabbling with Pascal (Borland/Delphi style) .

as we discussed in the first post of this https://preshing.com/20120612/an-introduction-to-lock-free-programming/

And it is hilariously stupid to call a bit of code ‘non locking’ when you are doing a polling loop instead.. Polling loops are evil – do a operating system level wait on something if at all possible!!!

I assume you’re talking about the data request section. The polling loop is a) a simplified implementation, b) yields for most of the time (OS-level).

I’d read your linked post, but since you’re into slinging around insults, I don’t feel the motivation.

This is a multithreaded buffer using busy-waiting with correctness enforced via atomic operations, right? I’m not sure what the advantage is when using busy-waiting rather than a normal lock; one side still has to delay until the other side unblocks it. If the intention is to reduce the latency of the common case — i.e. when the lock doesn’t need to be taken — then isn’t the cost of taking a lock with no blockers basically nil anyway?

I’ll also note that Ada’s rendezvous feature does have an implicit lock in it; the sender will block until the receiver is complete (because the receiver has access to the caller’s locals; it allows for extremely cheap RPCs; Ada rendezvous is amazing). But AFAICT the file read/write stuff is a layer on top of the ring buffer allowing the buffer to be used as a file cache, so the lock’s only taken when the buffer needs refilling/flushing, and you’ll need a lock there anyway.

Actually, having taken another look at the code… Ada’s `with atomic` is the same as C’s `volatile`. It doesn’t provide any memory barriers or atomicity operations; it just ensures that the compiler doesn’t cache the value locally. If you want a test-and-set or atomic-swap operation, you need to use a function out of `System.Atomic_Operations`. So how does this code protect itself against race conditions? I see lines like `free := free + locunread;`, where `free` is `with atomic`, but that’s not an atomic operation. I don’t see anything preventing another thread from running the same line of code at the same time. How does this work?

Ada’s Volatile aspect is more like C’s volatile keyword. The Atomic aspect provides additional features such as ensuring that all reads/updates to the variable are “indivisible” (see section C-6 paragraph 15). This means if memory barriers are needed, the implementation must use them. You are correct that it doesn’t protect the addition operation though, only direct reads and writes to the variable are indivisible. As you mentioned, System.Atomic_Operations is available

C’s volatile keyword is more like the Volatile aspect in Ada. The Atomic aspect in Ada gives many more guarantees such as indivisible reads/updates and sequential reads/writes at the processor level (which may require barriers on some machines). The Atomic aspect can indeed provide memory barriers (not all architectures require them but most modern ones do). However you are are correct to say addition operations are not atomic in and of themselves (Ada does not guarantee them to be and one must use System.Atomic_Operations as you suggested)

Didn’t know or realise this meaning of Ada’s `Atomic` yet. To a C++ programmer the term ‘atomic’ seems ‘somewhat’ misleading :)

I’ve made two examples on Compiler Explorer that show the effect of `Atomic` and of `System.Atomic_Operations`:

– Example _accessing_ (assigning) an Atomic Integer and an Atomic Record:

https://godbolt.org/z/Wv3orKaMb

– Example using `Atomic_Add()` of Ada 2022 package System.Atomic_Operations.Integer_Arithmetic:

https://godbolt.org/z/Evnc5bj3o

Further, `Atomic` implies `Volatile`, see http://www.ada-auth.org/standards/12rat/html/Rat12-5-5.html.

> To a C++ programmer the term ‘atomic’ seems ‘somewhat’ misleading :)

Apparently, Ada performing ‘magic’ would not entirely be unexpected ;)

For comparison, a C++ example using `+=` on an `atomic_int`:

https://godbolt.org/z/PhTWboY6d

To note, `ai += 77;` is an atomic operation with `std::atomic_int ai;`.

Didn’t know or realise this meaning of Ada’s `Atomic` yet. To a C++ programmer the term ‘atomic’ seems ‘somewhat’ misleading :)

I’ve made two examples on Compiler Explorer that show the effect of `Atomic` and of `System.Atomic_Operations`:

– Example _accessing_ (assigning) an Atomic Integer and an Atomic Record:

https://godbolt.org/z/Wv3orKaMb

– Example using `Atomic_Add()` of Ada 2022 package System.Atomic_Operations.Integer_Arithmetic:

https://godbolt.org/z/Evnc5bj3o

Further, `Atomic` implies `Volatile`, see http://www.ada-auth.org/standards/12rat/html/Rat12-5-5.html.

Intended to reply, and subsequently also did; please remove the non-reply comment; thanks.