Do they teach networking history classes yet? Or is it still too soon?

I was reading [Al]’s first installment of the Forgotten Internet series, on UUCP. The short summary is that it was a system for sending files across computers that were connected, intermittently, by point-to-point phone lines. Each computer knew the phone numbers of a few others, but none of them had anything like a global routing map, and IP addresses were still in the future. Still, it enabled file transfer and even limited remote access across the globe. And while some files contained computer programs, others files contained more human messages, which makes UUCP also a precursor to e-mail.

What struck me is how intuitively many of this system’s natural conditions and limitations lead to the way we network today. From phone numbers came the need for IP addresses. And from the annoyance of having know how the computers were connected, and to use the bang notation to route a message from one computer to another through intermediaries, would come our modern routing protocols, simply because computer nerds like to automate hassles wherever possible.

But back to networking history. I guess I learned my networking on the mean streets, by running my own Linux system, and web servers, and mail servers. I knew enough networking to get by, but that mostly focused on the current-day application, and my beard is not quite grey enough to have been around for the UUCP era. So I’m only realizing now that knowing how the system evolved over time helps a lot in understanding why it is the way it is, and thus how it functions. I had a bit of a “eureka” moment reading about UUCP.

In physics or any other science, you learn not just the status quo in the field, but also how it developed over the centuries. It’s important to know something about the theory of the aether to know what special relativity was up against, for instance, or the various historical models of the atom, to see how they inform modern chemistry and physics. But these are old sciences with a lot of obsolete theories. Is computer science old enough that they teach networking history? They should!

Just to clarify, email between users of different computers history) pre-dates UUCP (1976). SMTP came along later.

Where’s the “preview” button when you need it? “history)” should be “(history)”.

Was going to say that. Most technologies people think of coming to the consumer market existed in higher-end systems for decades prior.

The Mac 128K was the first (ish) computer to launch to consumers with a graphical desktop in 1984…………the same year that people at MIT were rewriting the pre-existing W windowing system into X to make it more portable.

Likewise, memory protection came to macs as standard with the IIx in 1988 and to windows…….with windows NT in 1993 (only a month early enough to predate it appearing with linux)……while it had been standard in high-end unix systems for nearly 20 years already (since at least the early 70’s, if not 1969 itself, pretty sure early unix required MMU units for the PDP11).

Linux is from 1991, not 1993. By 1993, at least FIVE distributions already existed

And yet it hasn’t been able to conquer the desktop. One has to ask what’s wrong.

Yes and also has not much to do with the Internet either. UUCP was first used on systems that were either direct connected to each other or were able to dial into each other. I worked with some VAX systems that dialed into a central system on a schedule to pick up and drop off mail and files. Yeah, I know UUCP is Unix to Unix but VMS had it as well.

One more remark from a really gray beard holding an original ARPANET TAC login card. IP addresses have nothing to do with phone numbers. An IP address is nothing more than a binary address (V6 is hex). The x.x.x.x format is just for humans that have a hard time with long strings of zeros and ones. Binary was used because it was the only universally accepted thing that all systems were guaranteed to be compatible with. Systems were still using octal so may not have understood hex. The network hardware was not very powerful (low cost microprocessors were not readily available) so bit banging binary was good enough. The 32 binary bits were more than enough for what was designed to be a military research network built around mainframe connected systems with terminal users.

Initially UUCP was used on closed networks where you did actually know the architecture and locations but the N+1 problem meant you were probably not directly connected to all of them. You were also probably not connected full time. So you used intermediate forwarders and store and forward logic.

The Internet actually killed off UUCP because you now had any to any connectivity and even before we had DNS, the ARPANET had downloadable host files that gave every system the ability to get to every other system. Primarily ARPANET was a collection of mainframe or minicomputers with terminal users so there were not that many end systems to deal with. The store and forward mechanism was unneeded once systems were connected full time.

Systems were using email locally from way back and UUCP was never really very universal because systems often did not participate and even less often accepted UUCP sources they did not know about. Remember most of this stuff was prompted by military and participating educational institutions engaged in research attached to the big government labs so trust was not a common thing. Access to a system normally involved calling someone on the phone, telling them what you needed access for and getting a local login.

Email was more of a convenience for the system admin types initially, the main focus was exchanging large data files efficiently. Think of a military base sending something like a supply inventory list to a higher headquarters for inclusion into a bigger database up the chain so someone could keep track of who has what. Also popular was payroll processing where a central organization sends a file to give private whatshisface $100 to a local payroll office.

My beard may not be the grayest, but it’s grayer than yours.

Yeah no. From the need to have some kind of idea where the message was going to go came the need for both.

Distance vector routing protocols predate UUCP, and definitely predate UUCP email. The need to route packets is as old as packet switching, and dynamic routing protocols aren’t much older.

Telling yourself nice stories isn’t exactly history.

Ethernet and TCP/IP predated UUCP, as of course did ARPANET. Even the term “internet” was being used in reference to ARPANET when UUCP came out).

To be fair, none of those things would become remotely mainstream for years to come, and I do think UUCP deserves credit for introducing a lot of people to ideas about network routing, email, etc., for the first time. But I think its main – and significant! – achievement was tying all these existing concepts together in a way that was incredibly practical and affordable compared to other options of the time (though definitely with emphasis on “of the time”).

Yeah but being there I can tell you that most systems using UUCP were not using Ethernet, TCP/IP or the Internet. It was groups of UNIX systems dialing into each other. Usually ad-hoc networks built by military and university systems and 99% of the time you knew exactly who you were talking to and just using UUCP to meet them at an upstream host. I think UUCP had very little impact on the development of the Internet, it was a step to get systems to exchange data BEFORE Internet connectivity. The Internet (and including its ancestors ARPANET, MILNET, and DDN) was the driving force that killed off UUCP.

To say something predated something else does not really tell much of the story since TCP/IP, ARPANET, MILNET, DDN were not publicly open systems and ethernet itself was not universally available on all platforms. It would be many more years before most mainframes gained ethernet or TCP/IP interfaces. Also, IP outside of the military industrial research community was not common until many years later. If I had to give you a date I would say that IP did not really become ubiquitous until the mid 80s. Remember the biggest LAN OSs (Networe and Microsoft) came standard with IPX and NetBUI in the mid 80s. TCP/IP was an expensive add-on option that did not work all that well on those systems.

Ethernet really also has nothing to do with Internet development. The Internet ran just fine on lots of network transports before ethernet was commonly used. The first BBN nodes I worked with were x25 connected to each other, serially to the mainframes, and dumb terminals connected to those.

The ARPANET was driven by two main requirements. First we needed a common addressing and protocol set that computers from every different manufacturer would be required to comply with in order to be used by the DoD. Second we wanted a survivable network architecture meaning no central (targetable) choke points that could continue to operate even if part of it was damaged or destroyed. This was a very cold war driven idea and as much as people like to point to their favorite Internet heroes, it was very much a Defense Department show. They had the budget and were the biggest buyer of computers so they were able to force everyone to get on board or else. If developed any other way there would have been no chance that people like AT&T, IBM, Borroughs, Digital and the like would have even agreed on anything.

The author was saying that networking history should be taught, and a small article talking about that isn’t a claim to be doing it. Meanie.

“Telling yourself nice stories isn’t exactly history.”

My favorite bit of Internet history is a book by an old network boy, M.A. Padlipsky: The Elements of Networking Style. Lots of interesting bits including the battle with ISO RM.

Nice to have lived as a very small part of this history, the traces are faint.

I got my first unix account on a vax 750 running bsd unix around 1980.

My uucp address was ..mcvax!enea!erix!bosse

Became sysadmin for one of the first 3 Sun 1 that was brought to sweden by our company’s technical director.

I installed our first Ethernet with vampire ethernet connectors that connected our vax and the Sun.

Soon we had other workstations as ICL Perq and Apollos conneted.

I had a coworker that wrote a gateway program that allowed the IBM users to send messages to the uucp world,

He was also a sendmail guru who assisted with many fixes to it.

My small claim to fame is to have signed the contract between the SNUS organization and kinnevik that became the first commercial internet provider Swipnet in Sweden.

I worked first with system administration for our Sun systems and later with the security for the company wide connectivity to internet until I retired after 40 years with the same company.

❤️

I mean, we had a globe-spanning telephone network before computing even came around. I hope they teach people about that in school at some point. That’s where you should look for the roots, not some Unix users in the ’70s. The Connections Museum has a very cool YouTube channel about it.

This series of articles opened my eyes to exactly what you said – I read this because of another HaD comment (sorry, can’t find which post for credit). 10/10 highly recommend

https://www.filfre.net/2022/01/a-web-around-the-world-part-1-signals-down-a-wire/

Telephony IS networking – not something tangential to computer networks where very similar problems were solved.

ITIL being (originally) a telephony standard was always presented to me as a cute factoid, rather than a key insight into how computer networking came to be. Samuel Morse and the telegraph is the beginning of the story of computer networks.

Exactly right. The global telephone network had over half a century of history by the time computing became important. By the 1950s large data networks existed at national scale; see the SAGE air defense system. Those circuit-based architectures used modems and later the digitized telephony transmission networks. By the 70s and 80s that very clunky architecture got adapted to IBM’s networking products–what became SNA–and to interconnect Unix machines for UUCP. Who remembers configuring phone numbers into Systems files? ✋🏻

That mid-century modem design was clunky, limited, but the impetus for research efforts that got us to ARPAnet, NSFnet, and today

There were lots and lots of networks before big I internet became a thing. In fact the entire idea of ARPANET was the DoD demanding an end to incompatible systems all talking on their own proprietary networks. We had contractors coming in every week to run a new network for some such new system. It got so bad that Strategic Air Command Headquarters in Omaha has a major ceiling collapse because there was so much cable on the ladder racks that they pulled out of the concrete. In fact even in the mid 80s we were arguing with Novell and Microsoft (don’t even get me started on Banyan Vines) to tell them they had to include native TCP/IP. Digital was STILL pushing their damn DECNET too. IBM was still running their proprietary protocols on all their major systems as well. These so called pioneers had to be dragged kicking an screaming into the TCP-IP world. The only thing that got them moving was the DoD forcing contract requirements on them. It had nothing to do with “doing the right thing”, they were all about trying to kill the competition by claiming their way to better. Before that we had tons of expensive gateways translating all of this garbage into TCP/IP for transport over the ARPANET/DDN backbone.

If asked to give you a date, I would say the battles all ended around 1990.

One other piece of this. In the late ’80s, maybe into the ’90s the DOD put forward the GOSIP or government OSI profile as the networking standards to be used within DOD systems. This was the set of protocols being developed under the international standards organization as the Open systems interconnect reference model. They develop protocols called CLNP and TP4. They were functionally like IP and TCP but managed under the ITU-T and ISO. Addresses would have been managed the way phone numbers are managed.

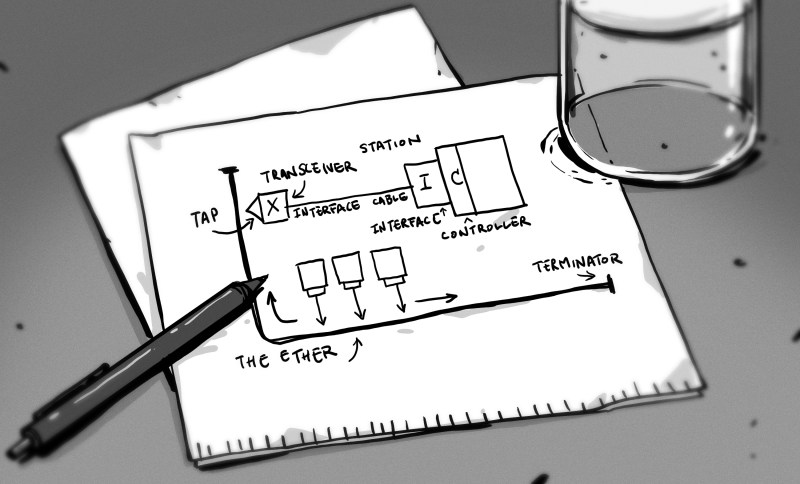

I was a new grad, working at Data General when Ethernet became “a thing”. The DIX standard shortly became IEEE 802.3, and we had thick yellow cable and vampire taps, quickly replaced with crimp N connectors and 3Com transceivers. I designed DG’s microNova Ethernet interface card. Still have some of that thicknet in the attic and a couple hundred feet feeding some antennas in the back yard.

When I was in Honolulu a few years ago, I made a pilgrimage to the Univ of Hawaii at Manoa, where there’s a marker honoring the developers of ALOHANET, the precursor to Ethernet.

One thing people don’t seem generally aware of is the issues caused by the thickness of early ethernet cables (Thick Ethernet). For example, the University of East Anglia (UEA, UK – home of the ‘climategate’ stitch-up in 2009) had a Sun lab in the late 1980s, full of, I believe Sun 3s: 68020 based workstations all linked to each other by Thick Ethernet.

But you couldn’t see any cables! Certainly not! Thick Ethernet cables snaked around in big arcs so they had an entire mezzanine floor underneath the lab just for them! I’m sure we weren’t the only ones!

10BASE-T arrived to much rejoicing :-)

Its funny, Thinnet was pretty rapidly accepted but lots of people did not trust 10BASE-T initially because everyone figured that twisted pairs could not possibly we as good as coax.

Thicknet was quite the challenge especially when the Air Force would not let us use vampire taps due to too many failures. We had to have teams ready all over the place so we could cut the network in multiple places simultaneously for splicing to minimize downtime. Does anyone else remember how stupid those sliding AUI connectors were? It was like someone decided to use the weakest possible connection for the heaviest least flexible cable.

With thinnet we had issues with geniuses unplugging cables from T connectors and removing terminators knocking down whole segments. The Air Force ended that by having us hard splice in all the T connectors and putting the terminators only in locked communication rooms.

All of that mess was better than token ring though :)

Many of us old guys have fond memories of the excitement in our youth. I used to stare at my ATT 3B1 in wonderment as it answered the line from asuvax where they were kind enough to give me access. Before that on IBM 360/75 but the 3B1 in my living room felt so much more personal.

I remember working on the 3B2 and someone asking me why we had a window air conditioner on our bench top. Pretty fun though, the first real System V platform I got to really mess with a lot. As usual the Air Force got a bunch of them from AT&T as part of a phone switch deal and they pretty much gave them to us and said “maybe you can find something to do with this thing”. In the Air Force a lot of times stuff would arrive in crates and absolutely no one would tell you what it was intended for. We got a bunch of DEC VAX workstations (very high end in the day) and they were sitting around for over a year when we just got them out and started playing with them. Turns out they were for some kind of weather information system that had gotten cancelled. First system I ran NCSA Mosaic on. Looked at a bunch of fancy inexplicable graphics from Fermilab and CERN.

Oh, the good old days. I remember “bang” notation for emails and configuring the modems to wake up and fetch email via UUCP from our connection to the backbone. In 1988 (well into the networked computers era), we were mostly an Apollo Domain Token Ring system at our shop. Nodes connected via a make-before-break-socket at the floor in each office. One fellow in Marketing had a Compaq Portable with an Apollo networking card installed that came with a BNC connector at the back of its case to connect to the token ring. The fellow in question couldn’t be bothered to disconnect with the socket at the floor, he just uncoupled the BNC from the Compaq and walked out the door at 5:00 pm. It drove the admins nuts because the Token Ring wasn’t a “ring” after that, and none of the other nodes could communicate with each other. The fellow’s name was Chuck, and we called it “chucking” the network. Things have gotten a lot better in the intervening 37 years.

I’ve been working on this, just to help me visualize the “other things going on” as I lived through ARPAnet and Internet (TCP/IP) history…

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1jTVYl5sFJaUAzV5tWW5LgIxx7V9zg1uhz1nRoEGCZNs/edit?usp=sharing

Any story on networking history and UUCP, should probably at least mention USENET.

Usenet/netnews in college on a Unix system started my interest in learning Unix.

I had DOS on my PC and learned AWK, C, vi and worked through some of The Unix Programming Environment. That lead to Minix and Linux and 30+ years as a Unix sysadmin.

Which is still around. People just have to pay for it instead of getting it free from their ISP.

I would say that porn and social media on the web pretty much killed Usenet just as SMTP/POP killed off UUCP. Working at an ISP at the time of the first broadband I can tell you that porn was a serious driver of the Internet adoption and speed race. Also a major driver of high bandwidth web hosting. Any study of Internet history has to accept that uncomfortable market driver in order to explain the phenomenon.

I really miss Usenet. I imagine ISPs started getting overwhelmed when people started putting in lots of large binaries (porn and pirated materials) .

It would thread and newsreaders could follow and filter what you already read. You could create killfiles that filtered out subjects, threads and individual commenters. Some readers could automatically assemble the uuencoded thing. For example, Dilbert was the 1st comic distributed on the internet. When you read the newsgroup, the reader could download it, create a gif and display it. This was before Mosaic came out.

Now we have RSS/Atom to read individual and web forums that have none of the filtering. Even mail was well adapted. It got archived, threaded, etc.

When I was doing Minix, I got all the patch diffs to go from 1.3 to 1.5 either from an mail to ftp service or newsgroups.

I think too many people are trying to relate UUCP to the Internet. One is a messaging protocol and the other is transport protocol. They evolved independently of each other. Similarly the USENET is really just an evolution of the bulletin board systems to a full time widely connected network. Today a lot of new engineers have this idea of an evolution path where one thing leads to another thing and it was not that. It was a lot of competing and often incompatible things adapting to a common transport network and continuous connectivity and market force they could not control.

In the email world there were lots of incompatible platforms (DaVinci email, Lotus Notes messaging, and others) that would not even talk to each other without third party gateways.

There was no higher moral decision to go compatible and Microsoft, DEC, IBM, and Novell were pushing incompatible systems into the late 80s. When the DoD made the decision to push the Internet into the public domain only market forces made everyone get on board and believe me they were still resisting it even after DoD mandated compatibility. They purposely made it as difficult as possible to deploy TCP by making it expensive and difficult (anyone remember Trumpet Windsock installations). Novell even tried to get the DoD to abandon TCP/IP in a very deep dive white paper extolling the reasons why IPX was much better (technically it might have been). The DoD finally had enough of it and forced the issue though big contract buys.

Even AT&T who was an initial ARPANET contractor made it nearly impossible to get a modem connected to a phone line. The US Air Force famously had to get phone lines installed with dial phones hard wire attached which were then promptly cut off as soon as the phone guy left so modems could be wired in. The AT&T network even used to disconnect dialed up connections regularly even though they knew these were data calls from the military systems. AT&T absolutely hated the idea of not ordering specially conditioned ultra expensive data lines so they could build the network the way they saw fit. For civilians they would routinely disconnect phone lines they found being used for data. At Strategic Air Command we had a big fight with AT&T over a phone line that suddenly could not run data. They claimed it was not built for data, it was a voice line even though we had used to for data for years. After extensive testing we found they had inserted a filter into the line specifically to mess with us. After some threats of force they removed them.

It is called “Epistemology”.

IHMO, one useful subject that should be taught properly in our public schools. The term doesn’t even come up in any discussions, yet, without knowing the context/history any thorough study might as well be called “in the middle of nowhere”.

I myself wonder how useful it really is to study Internet history. I lived through it in my field and really only find it useful to explain to new engineers how easy stuff is now in networking. Pretty much the network just works now and all the real exciting stuff is in the application and computing hardware world. It is kind of an embarrassment of riches in terms of reliability, bandwidth, and ease of connectivity now. The history is pretty hard to teach since it is at least hundreds of disparate paths leading to mostly dead ends and a few winners for completely differing reasons (economic, political, personal). It kind of like trying to teach the history of the world. From who’s perspective matters. Coming from the military world, I can tell you that what I know of the Internet history is far different from what I have seen published here and elsewhere.

Where some see brilliant geniuses creating thing for the betterment of the world, other see the worlds biggest military industrial titans going to war with each other to dominate the space. The real truth is probably somewhere mixed in there and we are probably too close to write it now.

No one wants to teach the kids that the Internet was a US attempt to build a military computer network that could survive a Soviet first strike and be able to launch a retaliatory strike. That is exactly what ARPANETs requirement was.