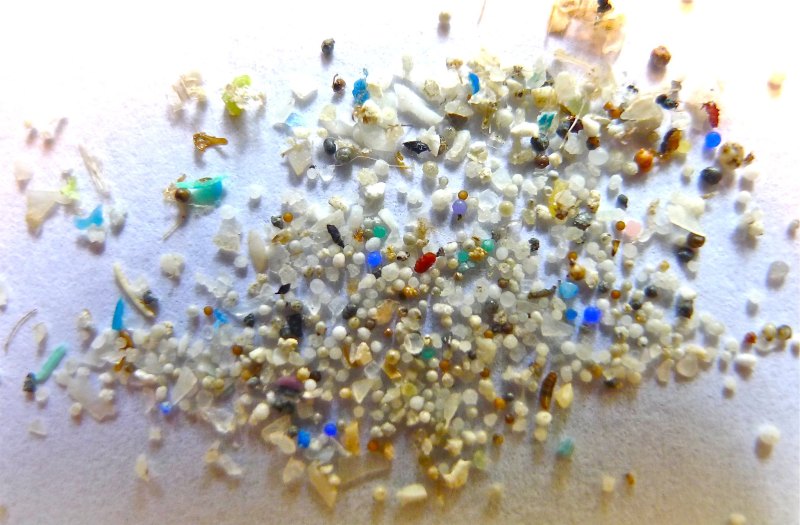

Like the lead paint and asbestos of decades past, microplastics are the new awful contaminant that we really ought to do something about. They’re particularly abundant in the aquatic environment, and that’s not a good thing. While we’ve all seen heartbreaking photos of beaches strewn with water bottles and fishing nets, it’s the invisible threat that keeps environmentalists up at night. We’re talking about microplastics – those tiny fragments that are quietly infiltrating every corner of our oceans.

We’ve dumped billions of tons of plastic waste into our environment, and all that waste breaks down into increasingly smaller particles that never truly disappear. Now, scientists are turning to an unexpected solution to clean up this pollution with the aid of seashells and plants.

Sticky Solution

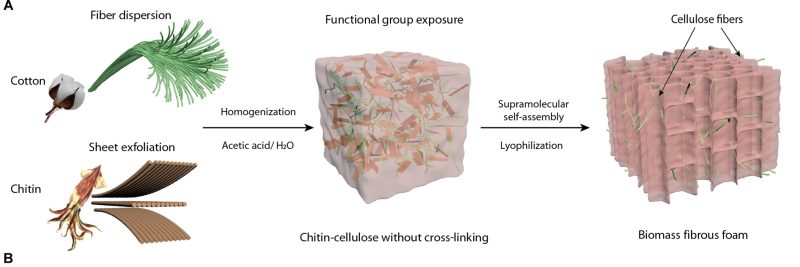

A team of researchers has developed what amounts to a fancy sponge for sucking up microplastics, made using readily available natural materials—chitin from marine creatures, and cellulose from plants. When these materials are processed just right, they form a super-porous foam that readily “adsorbs” microplastic material, removing it from the water. If you’re not familiar with the term, adsorbtion is simple—it refers to material clinging on to the surface of a solid, rather than being absorbed into it.

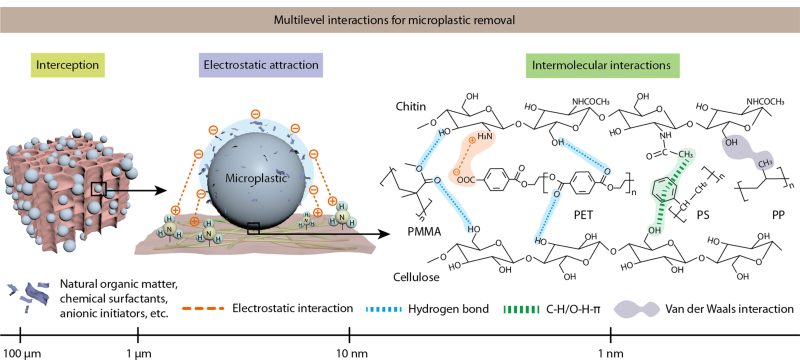

To create the material, researchers took chitin and cellulose, and broke down the natural hydrogen bonds in both materials, which allowed them to be reconstructed into a new foam-like form. The result is a very porous material that has negatively- and positively-charged areas on the surface that can effectively bond with microplastic particles. Indeed, the foam effectively grabs plastic particles through a combination of electrostatic attraction, physical entrapment, and other intramolecular forces. It both attracts microplastics via physical forces and entangles them, too.

The foam performed well in testing, capturing from 98% to 99.9% of microplastics. Even more impressive, the foam maintained a removal efficiency above 95% even after five usage cycles, a positive sign for its practical longevity. The material shows particular affinity for common plastics that show up in litter and other waste streams—like polystyrene, polypropylene, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

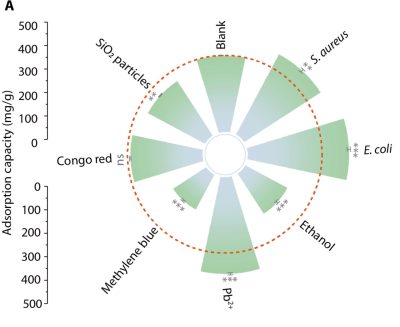

Of course, polluted water on Earth is a more complex mix than just water and plastic. Take a sample and you’re going to find lots of organic matter, bacteria, and other pollutants mixed in. The researchers put their foam through its paces with four different samples from real-world contexts—taken from agriculture irrigation, lake waters, still water, and coastal waters. While contaminants like ethanol and methylene blue cut the adsorption capacity of the foam by up to 50%, that wasn’t the case all round. Surprisingly, some contaminants actually improved its performance. When heavy metals like lead were present, the foam’s plastic-capturing ability increased, and it gained a similar benefit from the presence of bacteria like e.Coli. Testing like this is crucial for proving the foam’s viability outside of simple laboratory tests. Removing plastic from clean water is one thing; removing it from real samples is another thing entirely.

The beauty of this approach lies in its simplicity and accessibility. Unlike some high-tech solutions requiring expensive materials or complex manufacturing, the foam is made out of materials that can be sourced in abundance. Chitin is readily available from seafood processing waste, and cellulose can be sourced from agricultural byproducts. The research paper also explains the basic methods of preparing the hybrid foam material, which are well within the abilities of any competent lab and chemical engineer.

While this foam won’t single-handedly solve our ocean plastic crisis, it represents a promising direction in environmental remediation. The challenge now lies in scaling up production and developing practical deployment methods for real-world conditions. Developing the foam was step one—the next step involves figuring out how to actually put it to good use to sieve the oceans clean. Stopping plastic contamination at the source is of course the ideal, but for all the plastic that’s already out there, there’s still a lot to be done.

Featured image: “Microplastic” by Oregon State University

We could build a truly massive parallel facility of centrifugae (say the size of Los Santos) that would remove microplastics leaving behind water. It could also be used to extract minute quantities of uranium from seawater so that we may finally embrace the new era of affordable nuclear power.

how do you propose we separate the undesirable particulate and the nuclear particles you desire from the microorganisms that are essential to the food chain

There’s this funny property of organisms… They tend to make more of themselves, without human intervention (sometimes despite it).

Sure but my point is that filtering the entire ocean through centrifuges is going to have some indeterminate effects on the ecosystem to say nothing of the enormous power requirement and subsequent pollution that would cause.

Might really ruin a surfers day

“The size of Los Santos”… You are aware Los Santos is entirely fictional right? It doesn’t have a size (other than a bit/byte count)

The real question is how do we deal with Microplastics in our bodies.

I don’t think people understand that we, not just the ocean, are now all walking around with micro plastics in our bodies. Our brains, our organs, reproductive organs, our blood this is an unspoken epidemic being played down as an environmental issue but it is an immediate threat to human health.

Cleaning up the world, forcing companies to stop polluting the planet, and moving away from plastic will help us not build up more plastic in our bodies, but we’re all basically infected with microplastics thanks to these companies polluting everything with little option for customers to use alternatives and paying off people to allow it.

I don’t think people understand, we are all infected with tons of micro plastics in our bodies now and nobody knows how bad that’s going to impact our lives but we’ve already seen a decline in fertility and signs of an increase in neurological problems.

Exactly.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch Isn’t What You Think It Is

It’s not all bottles and straws—the patch is mostly abandoned fishing gear.

3 Jul 2019

As it turns out, of the 79,000 metric tons of plastic in the patch (a absolutely infintesimal amount compared to the mass of the pacific ocean), most of it is abandoned fishing gear—not plastic bottles or packaging drawing headlines today.

The study also found that fishing nets account for 46 percent of the trash, with the majority of the rest composed of other fishing industry gear, including ropes, oyster spacers, eel traps, crates, and baskets. Scientists estimate that 20 percent of the debris is from the 2011 Japanese tsunami.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

30 Jul 2015

…while the name “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” may conjure up an image of a floating island of debris, the actual garbage patch itself was actually difficult to see.

For many people, the idea of a “garbage patch” conjures up images of an island of trash floating on the ocean. In reality, these patches are almost entirely made up of tiny bits of plastic, called microplastics. Microplastics can’t always be seen by the naked eye. Even satellite imagery doesn’t show a giant patch of garbage. The microplastics of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch can simply make the water look like a cloudy soup. This soup is intermixed with larger items, such as fishing gear and shoes. The seafloor beneath the Great Pacific Garbage Patch may also be an underwater trash heap. Oceanographers and ecologists recently discovered that about 70% of marine debris actually sinks to the bottom of the ocean.

The larger floating items are teeming with life:

17 April 2023

Extent and reproduction of coastal species on plastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre

Analysis of rafting plastic debris in the eastern North Pacific Subtropical Gyre revealed 37 coastal invertebrate taxa, largely of Western Pacific origin, exceeding pelagic taxa richness by threefold. Coastal taxa, including diverse taxonomic groups and life history traits, occurred on 70.5% of debris items.

But NOTE what shows up in an image search for “Pacific Garbage Patch”:

https://duckduckgo.com/?q=%22Pacific+Garbage+Patch%22&atb=v314-1&t=chromentp&iax=images&ia=images

The actual garbage patch:

https://assets.theoceancleanup.com/scaled/1200x/app/uploads/2023/11/Medium-231019-Meetingday-06.jpg

The study, published in Nature Medicine on Feb. 3, (2025) confirms that tiny plastic fragments are passing through the brain’s protective blood-brain barrier, potentially impacting health and cognitive function.

Researchers from the University of New Mexico (UNM) tested autopsy samples from 2016 and 2024. They found that over just 8 years, the amount of microplastic fragments in the brain has increased by about 50 percent. Brain samples from 2024 contained microplastics equal in weight to a plastic spoon.

Brains affected by dementia showed significantly higher concentrations of these plastic particles.

Finding such high concentrations in the brain was unexpected and alarming, Matthew Campen, lead researcher and toxicologist, told The Epoch Times during a press conference.

“People are simply being exposed to ever-increasing levels of micro- and nanoplastics,” said Campen. The particles are so small, they’re roughly the width of two COVID viruses standing side by side, he noted.

They pyrolytically decomposed (“burned”) the tissue to analyze it, and found molecules like those they expect to see from nanoplastics.

They also found some samples of brain that contained 50,000 ppm “plastic”. That’s five percent!

I think the data warrants a bit of reexamination. Especially if it’s being trumpeted by the likes of Epoch Times.

Actual paper rather than a copied news summary for those interested:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03453-1

Worth taking a look at their methodology.

From that paper, which used a fairly new technique for measuring possible microplastics:

“Our estimates of polymer mass concentration could be impacted by several factors that may lead to overestimation or underestimation. The KOH digestion extensively eliminated biological material from the pellets through saponification of triglycerides and denaturing of proteins (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, the final pellets still contained unknown residual biomatrix, which could present challenges for mass spectral interference. KOH reduced the liver and kidney mass by 99.4%, while the brain samples were reduced by 91.8%, that is, the resultant average pellet mass derived from 500 mg of starting material was approximately 3 mg and 41 mg, respectively. This discrepancy is proportional to, and consistent with, the mass of the polymer measured. However, unknown organic molecules likely remain and influence the resultant Py-GC/MS spectra.”

What they’re assuming is the the remaining material after chemically digesting triglycerides and proteins is entirely microplastics. This is likely not the case.

This is one of those ‘more research needed’ conclusions, which unfortunately has been taken up by media as a highly conclusive settled fact.

I think you are really underestimating how much water is in the ocean. You would need many gigantic facilities all over the world and they would use terawatts of energy.

Nonsense. A terawatt is a unit of power, not energy.

Who is “we”?

” scaling up production and developing practical deployment methods for real-world conditions.” . Those are engineering problems, to be solved by engineering.

The lingering problem, not easily solved and conveniently ignored : Who will pay for all of this ?

Whomever currently has the treasury hostage.

Well, if they get it working for plastics, now make it work for useful stuff, like all the lithium, uranium, deuterium, gold, copper, etc. They are all present in far greater concentrations in seawater than microplastics, but currently economically not worthwhile to extract. Maybe what they are learning here will help avoid the mess we make when we extract such goodies from dry dirt.

Then again, maybe we will learn that the making the energy required to collect all those microplastics costs the environment far more than just leaving the stuff in place to get removed by natural processes.

I’d submit that captured plastic particles -are- “useful stuff.” Feed it into a pyrolysis rig and recover light crude. Since the oil is the outcome of processing existing material, unlike pumping crude from the ground, it is in effect carbon neutral.

Except it will cost more in energy to extract it from the water than you would ever recover by burning it. It will also cost more (in energy, money, or environmental impact) to extract it from water than it would to get that “light crude” by other means.

As a saleable byproduct, perhaps reprocessing it is preferable to landfill, but I doubt it’s a net win, environmentally.

Really, if you want the material, catch it before it gets dispersed in the water.

That might work with some types of plastic, but on the whole natural processes are not removing plastics at all, just breaking ’em into smaller bits. And those plastics are having detectable impacts on life down there (some of it anyway). If that leads to breaking down the food chain its hard to do worse.

Also the energy required to collect ’em can almost certainly be entirely free of extra environmental impact – use the excess peaks of renewable generation to make these things etc. Even if you assign an equal share of the environmental impact of that wind turbine/solar farm that just makes the whole grid look better using the greener power sources for a higher proportion of total demand!

And then we find out that somehow the food chain relies on those minerals, and we kill the planet again.

Sounds slightly faster than letting dead fish drag the pollutants to the bottom of the ocean. We could release it in mass quantities off the coast of China :)

Already happening, in case you didn’t notice.

Also, FWIW, that paper is entirely Chinese-authored research.

What’s with the goofy “Little Prince” tiny planet circular bar graph? What a confusing way to present eight simple numbers.

similar plots were used for metal contamination of bird feathers, each sample location had a unique star shape. Perhaps they were looking at different formulations of the foam.

Something is going to start eating that stuff pretty soon. Probably more than one thing. There’s too much energy to be had for life not to exploit it. It’ll be like when fungi figured out how to digest cellulose.

Not sure what that’ll do, mind you, and it may not be good at all…

It’s getting eaten but it’s not getting digested. However, there are some bugs that will consume some variant styrofoam. The problem is that they emit plenty of CO2 as a byproduct. The bigger problem is that there are so many different kinds of plastics. Specifically, if some germ evolves to consume one type of plastic, it may die off because it ate the wrong kind of plastic which keeps it from proliferating. Evolving something that can consume all our plastics would take a few centuries and in the meantime, things are going to die off from consuming too much.

Surely there is a technological solution with unknown side effects that we could spend tax money on. Maybe we should stop consuming the same amount of harmful shit and disposing of it in the same way while blaming everyone else.

A bit of a rant.

I appreciate the efforts. Every possible solution should be investigated. I doubt (I really hope I’m wrong) that this won’t work on the scale needed to actually filter out micro plastics, but if there is a chance, it’s worthwhile research. In the past I’ve done some work for the ocean cleanup project and currently I work for a company that’s doing environmental research.

Cleaning it up is great, but stopping the pollution coming in is a disaster by itself. You might think that plastic bags, bottles and straws might be a huge problem, but that’s just a drop in the bucket. The vast majority (depending on research referenced, between 60 and 72%) of plastics in the oceans are fishing nets. These are bottom trawling nets that can easily get caught on something on the bottom of the ocean, resulting in the net to be lost. These nets are incredibly large and this is an extremely common thing to happen. Depending on the source used, the estimates for the biggest country that uses this method is between half a million to well over a million fishing vessels. Sadly, I only know of three countries (Greece, Sweden and Chile) that banned the use of these nets.

Another portion comes from natural disasters. Hurricanes, tsunami’s and other floods bring a lot of debris into the oceans.

There is a lot of waste being dumped into rivers, sadly, but that’s a tiny portion of the plastics in the ocean. We, and many of our business comrades, are working on finding solutions to lower that last part. Special nets in rivers that don’t limit the movement of vessels, reroutes of rivers with filtration, drain pipe filtration and other methods that could limit the waste in highly polluted rivers. But even that is sadly not the end all solution to these problems.

I wish we had good quality materials that are cheaper than plastics, especially for fishing nets.

Wild that a website for hackers and programmers can’t figure out how to fix their quote formatting.

I throw my car batteries in the ocean to help soak up the microplastics.

I didn’t think much about micro plastics until my neighbors scattered a bit of glitter down the hall as they disposed of their Christmas tree. After vacuuming 4 times, I still see a sparkle now and then. The really small stuff must be just as hard to get rid of.

Ocean Cleanup is making a nice work. Go check it.

Hmm. Website not usable: renders page, but that’s it. Nothing clickable, can’t scroll. (Firefox on Windows, no plugins)

I’d love to see a world wide ban on GLITTER!!

I expect a ocean microorganism will evolve that eats common plastics. Or a microbe that sticks to plastic as an easy way to stay near the surface, and agglomerates microplastics into larger clumps.

Don’t forget microplastics in ready form, they’re really close to all of us. Most clothes are made with some or all polyester fibers. Fast fashion is pushing stuff that goes to rags quickly. Laundry is a source everywhere except when natural fibers are the only form of fabric. At treatment it either goes on fields as sludge or on down the river.

We don’t. It’s another exaggerated non-issue for first worlders to clutch their pearls about since they are too privileged to have real problems to deal with.

Heart disease, diabetes, cancer, etc. are pretty serious problems bro

I feel like I’ve seen so many good solutions for microplastics, desertification, carbon sequestration, etc, and then the author graduates because it was a good thesis, and we never see it again.

Improving the environment isn’t profitable. In the short term it involves expensive cleanup for no immediate gain, and in the long term it involves a reduction in economic activity which scares the rich people. Nobody in charge wants to take the blame for all that, so it’s business as usual until we choke on our own waste products like bacteria in a petri dish.

prevent: Ban the use of plastic fishing nets. Generate hemp nets instead (make them cheap or subsidize)

I can’t remember where, but I saw something where they figured out that most of the plastic in the ocean is from fishing nets. Do that, plus plug that one river in china that is responsible for MOST of the trash in the ocean, and we would probably be fine

There are no substitute for limiting production and recycling.

I am shocked no one else has said this and that this is at the bottom of the comment chain. This is the easiest, and most important answer. We can figure out how to clean things up when we get there. But at the rate we produce and poorly dispose of plastic materials the likelihood of meaningful success is getting lower by the day. Have to fix the burst pipe before ordering a new Brita filter.

Except it really isn’t an answer in this case – if you wait until you have fixed ‘the burst pipe’ before you start researching how to make a functional ‘Britia filter’ then things will continue to get worse even if all plastic use was entirely banned today. There is decades of discarded stuff working its way into the oceans, so while more responsible use would be a darn good idea there is absolutely a need to figure out a viable way to tidy up after ourselves too. This is not a case where one logically should always follow the other.

Calling it micro plastic is like calling the calf at the petting zoo veal at dinner time. Nylon, polyester, spandex, tires, Tupperware…..