The familiar five volts standard from back in the TTL days always struck me as odd. Back when I was just a poor kid trying to cobble together my first circuits from the Forrest Mims Engineer’s Notebook, TTL was always a problem. That narrow 4.75 V to 5.25 V spec for Vcc was hard to hit, thanks to being too poor to buy or build a dedicated 5 V power supply. Yes, I could have wired up four 1.5 V dry cells and used a series diode to drop it down into range, but that was awkward and went through batteries pretty fast once you got past more than a few chips.

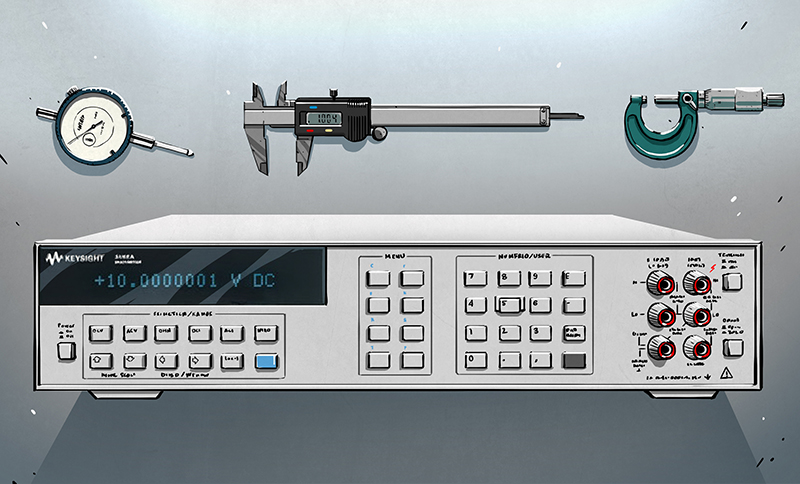

As a hobbyist, the five volt TTL standard always seemed a little capricious, but I strongly suspected there had to be a solid reason behind it. To get some insights into the engineering rationale, I did what anyone living in the future would do: I asked ChatGPT. My question was simple: “How did five volts become the standard voltage for TTL logic chips?” And while overall the answers were plausible, like every other time I use the chatbot, they left me wanting more.

Circular Logic

The least satisfying of ChatGPT’s answers all had a tinge of circular reasoning to them: “IBM and other big computer makers adopted 5 V logic in their designs,” and thanks to their market power, everyone else fell in line with the five volt standard. ChatGPT also blamed “The Cascade Effect” of Texas Instruments’ standardization of five volts for their TTL chips in 1964, which “set the tone for decades” and forced designers to expect chips and power supplies to provide five volt rails. ChatGPT also cited “Compatibility with Existing Power Supplies” as a driver, and that regulated five volt supplies were common in computers and military electronics in the 1960s. It also cited the development of the 7805 linear regulator in the late 1960s as a driver.

All of this seems like nonsense, the equivalent of saying, “Five volts became the standard because the standard was five volts.” What I was after was an engineering reason for five volts, and luckily, an intriguing clue was buried in ChatGPT’s responses along with the drivel: the characteristics of BJT transistors, and the tradeoffs between power dissipation and speed.

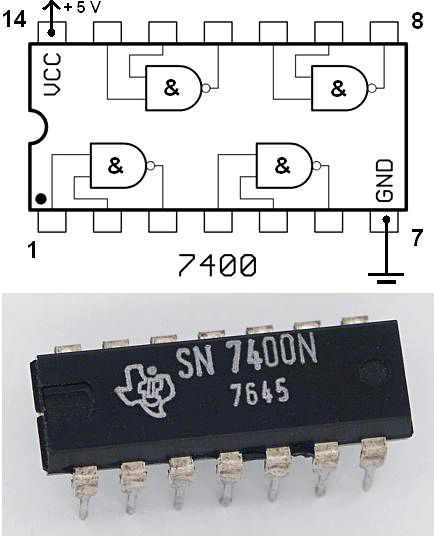

The TTL family has been around for a surprisingly long time. Invented in 1961, TTL integrated circuits have been used commercially since 1963, with the popular 7400-series of logic chips being introduced in 1964. All this development occurred long before MOS technology, with its wider supply range, came into broad commercial use, so TTL — as well as all the precursor logic families, like diode-transistor logic (DTL) and resistor-transistor logic (RTL) — used BJTs in all their circuits. Logic circuits need to distinguish between a logical 1 and a logical 0, and using BJTs with a typical base-emitter voltage drop of 0.7 V or so meant that the supply voltage couldn’t be too low, with a five volt supply giving enough space between the high and low levels without being too susceptible to noise.

But, being able to tell your 1s and 0s apart really only sets a minimum for TTL’s supply rail. Why couldn’t it have been higher? It could have, and a higher Vcc, like the 10 V to 15 V used in emitter-coupled logic (ECL), might have improved the margins between logic levels and improved noise immunity. But higher voltage means more power, and power means heat, and heat is generally frowned upon in designs. So five volts must have seemed like a good compromise — enough wiggle room between logic levels, good noise immunity, but not too much power wasted.

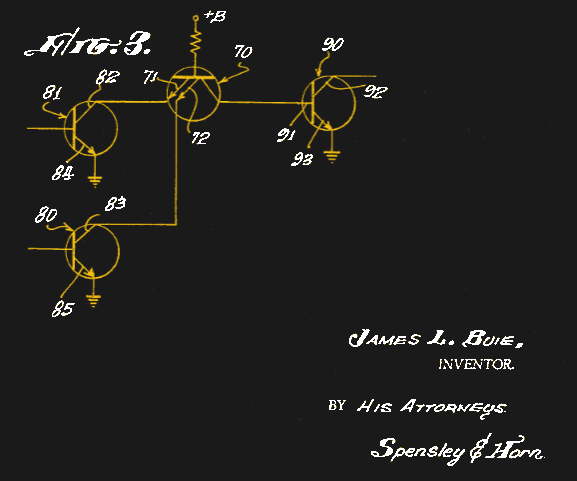

I thought perhaps the original patent for TTL would shed some light on the rationale for five volts, but like most inventors, James Buie left things as broad and non-specific as possible in the patent. He refers only to “B+” and “B-” in the schematics and narrative, although he does calculate that the minimum for B+ would be 2.2 V. Later on, he states that “the absolute value of the supply voltage need be greater than the turn-on voltage of the coupling transistor and that of the output transistor,” and in the specific claims section, he refers to “a source of EMF” without specifying a magnitude. As far as I can see, nowhere in the patent does the five volt spec crop up.

Your Turn

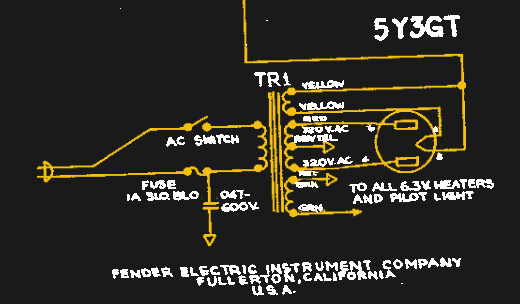

If I were to hazard a guess, the five volt spec might be a bit of a leftover from the tube era. A very common value for the heater circuit in vacuum tubes was 6.3 V, itself a somewhat odd figure that probably stems from the days when automobiles used 6 V electrical systems, which were really 6.3 V thanks to using three series-connected lead-acid cells with a nominal cell voltage of 2.1 V each.

Perhaps the early TTL pioneers looked at the supply rail as a bit like the heater circuit, but nudged it down to 5 V when 6.3 V proved a little too hot. There were also some popular tubes with heaters rated at five volts, such as the rectifier tubes found in guitar amplifiers like the classic Fender “Champ” and others. The cathodes on these tubes were often directly connected to a dedicated 5 V winding on the power transformer; granted, that was 5 V AC, but perhaps it served as a design cue once TTL came around.

This is, of course, all conjecture. I have no idea what was on the minds of TTL’s designers; I’m just throwing out a couple of ideas to stir discussion. But what about you? Where do you think the five volt TTL standard came from? Was it arrived at through a stringent engineering process designed to optimize performance? Or was it a leftover from an earlier era that just happened to be a good compromise? Was James Buie an electric guitarist with a thing for Fender? Or was it something else entirely? We’d love to hear your opinions, especially if you’ve got any inside information. Sound off in the comments section below.

This isn’t a mystery. The choice of 5v was a function of achieving the necessary performance within constraints of the bipolar transistors used at the time.

Some of this stuff was done based on “we screwed around with some of the parameters and that’s what we got” For all we know, it might have started out as “it’s going to be somewhere between 4 and 7 volts” and five eas what the early process worked best at and then from then on you’d be stuck with that for compatibilities sake.

6.3V AC gets rectified to 5V DC after going through two diodes

also consider: all circuit have capacitance. much of the power dissipated happens during switching transients, the higher voltages used – the more switching current. that and the mentioned things like: transistor capabilities, input currents, and noise margin all contribute to the compromise. it has nothing to do with 5v tube power supplies.

TTL was 5V because the earlier DTL, with which it was compatible, was 5V. That doesn’t really answer the question, though.

ECL did not use 10-15V. Maybe you were thinking of PMOS, which was usually around 17V, but later made to work down to about 7V, for use in calculators to run on 9V batteries.

ECL generally used 4.5 to 6 volts, depending on the specific family, and was usually negative with respect to ground. 10K, the most common ECL family, used -5.2V,. Starting in the 1980s, it became somewhat more common to run ECL on a positive supply, giving rise to the terms NECL and PECL to distinguish them. Other than level translators, the chips weren’t different, just the conventions for powering them.

In my experience, 10K ECL works fine on -5.0V, as long as you’re not connecting it to other ECL at -5.2V, SE that makes me wonder why Motorola chose 5.2 rather than 5.0.

I thought maybe the given bipolar process at the time…they didn’t want to create thick oxide…so it was a tradeoff…..thinner xide allows enough Vcc….

The design of TTL itself, and the use of bipolar transistors pushes you towards a somewhat specific voltage range. It’s bigger than 4.75-5.25, but you the freedom has a limit. I can show you the breakdown if you look at the 7400 schematic (this is the “original” 74 TTL, before the 74S, 74F, 74LS, … series appeared): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transistor%E2%80%93transistor_logic#/media/File:7400_Circuit.svg

A key part of TTL design is it’s output “totem pole” circuit. Two NPN transistors (V3, V4 in that schematic) enable the high or low values. The low value goes through a collector-emitter junction, which can go up to around 0.4V for high sinking currents (which allow a large fanout, desired in TTL design which was competing with RTL that had poor fanout). That gives you VOL(max)=0.4V, you want VIL to be bigger than that to tolerate some noise. On the high value you have a bigger drop: the base of the high transistor is at most VCC, and from there you have two PN junctions (on V3 and V5) to go across before reaching the output. Assuming a drop of roughly 0.7V per junction, your output will be VCC-1.4V . But if you’re driving a bit of load, you also have the resistive drop on R3. A TTL high load can’t be too big, but you could get a bit more than 0.05V, let’s round that to 0.1V. So in practice, your output VOH(min) will be around VCC-1.5V.

So far we’ve accounted for 1.9V (0.4 + 1.5), which still requires adding some margin on the low side, on the high side, and between the high/low values. You can’t just put them too close, even in a noise-free world: NPN transistors don’t toggle like a switch, instead they get quite linear in the threshold area, so you’ll have very bad edges between low and high. If you try to design a circuit that “toggles” current flow at specific voltages, multiples of the PN junction drop are natural stopping points for a threshold. You could use one drop (choose 0.7V as the threshold), and with no noise immunity between low and high you could have VIL<0.7, VIH >0.7; I guess that’s where the 2.2V (VCC=VIH+1.5V) in the patent originates. But that’s before adding noise immunity and nicer switching edges. So it’s better to choose two voltage drops as threshold. That allows to put VIL in a safe spot between 0.4V and 1.4V (with some breathing room), and VIH should start somewhat above 1.4V. (and VCC will be at least VIH 1.5). You probably could get away with a VCC of 3.5V and things will work decently…. which is what LVTTL became later. Below that it’s tricky without a very different design (assuming you stick with NPN transistors, which was a design constraint in TTL)

How far up can you go in VCC? well, looking now at the way TTL does inputs (V1 in the diagram) which is a bit of a funny way to use a transistor (using the emitter as an input) gives you a hard limit. If the inputs to this circuit are tied high directly to VCC , the base-emitter of V1 is reverse biased, and the transistor goes into reverse mode and essentially works as a base-collector diode (that’s the normal way TTL inputs operate). The base has a 3 x PN-junction path to ground (V1, V2, V4), so it will be internally at 2.1V. The emitter-base junction is reverse biased, and if you look at usual bipolar transistor specs, these junctions are usually quite weak, and breakdown at low voltages (you’ll see numbers of around 5 to 6V in transistors like the PN2222 or BC547). That will give you a hard limit of ~7-8V, and again you don’t want to operate right next to the point where your transistor catches fire. So in summary, TTL could have been designed somewhere between ~3.5V and ~6.5V VCC and probably work in a similar way.

The next paragraph is speculation, but sounds reasonable to me:

Starting from the numbers above, you could say “I need a range of at least 0.4V for low voltages, at least 1.5V for high. Let’s double those to 0.8V and 3V, giving a range of <0.8V for VIL, and >VCC-3 for VIH.” i.e. my hypothesis is that TTL chose a 2x safety factor for those ranges, somewhat arbitrarily. Then, you choose 1.4V (two junction drops) as the lowest reasonable threshold point for the circuit. That means you get around 0.6V of noise margin between VIL and the threshold (1.4V – 0.8V). If you decide to have the same noise margin above the threshold, that puts you at 1.4V + 0.6V = 2.0V. So you can set VIH from 2 to 2+3V, which gives you a VCC of… 5V :)

5v Filament transformers were readily available in the 60’s and they provided LOTS of current. Hams would sometimes leave a 5v filament transformer connected to their loop antenna when not in use to prevent ice build-up in the winter.

5V was a practical measure to provide enough headroom for voltage drop across multiple transistor junctions. It became defacto standardized through the 74 series.

I’m puzzled by the variance folks report with LLMs. I asked ChatGPT (single try) “Why is the TTL voltage 5 volts?” and got a physics-driven answer (stacked V_BE headroom + noise margin + fan-out + power) that, to me, is as good as I’ve seen in this discussion. It also mentioned 5 V having been common for tube heaters, and mentions 74xx and later designs of the period standardizing it for easy interfacing—no causality inversion there that I can see.

Here’s the “in short” it volunteered at the end of the response:

“TTL’s 5 V supply arose from the needs of silicon BJTs — a few diode drops, plus margin for noise and current drive — and stuck because it worked, matched existing power rails, and became industry standard before MOS logic took over.”

Genuine question: what’s driving our “different realities” here—model/version drift, prompt framing (“engineering reason” vs “history”), sampling randomness, or evaluation bias?

I took this question out another door. Early relay controlled industrial equipment used 120VAC or 1 leg of three phase 440VAC stepped down. 24 volts was adopted as a standard mostly for personal safety. The rational is somewhat circular like 5 VDC for TTL. 24VAC is common for doorbells and thermostats in the home environment. Heavy equipment and military vehicles use(d) 24VDC. Telco legacy is -48VDC. My answer is critical mass requires standardization.

5 volts AC as the rectifier heater voltage is an industry standard, not unique to Fender. Also, it is separate from the 6.3 or 12.6 volt supplies as, the cathode in the high tension rectifier it is typically hundreds of volts above ground.

Pretty sure it’s 5V because USB is 5V. (duh)

Why I like 74HC chips, they are 2-6V with input levels that scale with Vcc and are nice and symmetrical.

The precursors to ttl logic get so overlooked. RTL, DTL, etc. RTL ran on 3.6v for example but there are reasons it didn’t survive. (Slow and fan-in issues, not to mention current draw) Many of these circuits that became ic chips were originally built as discrete circuits on pc boards in a time before chips. DTL was all over IBM and DEC designs but look cumbersome today due to using -6 and -6v and 0 and -12v for NPN and PNP based logic respectedly. TTL is the first logic that seemed to rely on direct input to the transistor so settling on voltage that worked best for the transistors in input and output stages used makes sense and Buie set the stage at Sylvania and everyone else followed. Recall that like 70% of all chips in the 60s were going to the military, who live by standards.

The Vebo of many bipolar transistors is 5V, and one comment I came across just now said that the process of optimising Hfe converges on this potential. I am not skilled in transistor design so cannot confirm or deny this, but it seems plausible. So perhaps 5V was chosen to be the highest voltage that would not destroy the active TTL devices, whilst maximising the system noise immunity.

Supporting this contention: I was taught to pull up unwanted TTL inputs via a resistor (2k2 was used for this) rather than a direct connection to Vcc so that any momentary spikes on the power rail would not damage the chip.

It may be relevant that the true Zener effect has a maximum around 5V. (Zener diodes above about 5.6V are actually relying on the avalanche breakdown).

As all this is speculation. I should love to know the real reason!