After the Norman invasion of England, William the Conqueror ordered a great reckoning of all the lands and assets owned. Tax assessors went out into the country, counted sheep and chickens, and compiled everything into one great tome. This was the Domesday Book, an accounting of everything owned in England nearly 1000 years ago. It is a vital source for historians and economists, and one of the most important texts of the Middle Ages.

In the early 1980s, the BBC set upon a new Domesday Project. Over one million people took part in compiling writings on history, geography, and social issues. Maps were cataloged, and census data recorded. All of this was printed on a LaserDisk, meant to be played on an Acorn BBC Master. Now, 30 years on, hardly anyone can read the BBC Domesday Project. Let that be a lesson, kids: follow [Jason Scott] on Twitter.

Even though Acorn computers and SCSI LaserDisks and coprocessors are dying, that doesn’t mean the modern Domesday Disk is lost to the sands of time. This project aims to duplicate the Domesday Disk, and in the process provide a means to archive all LaserDisks. It’s a capture card for LaserDisks, and it also means we can finally make a good rip of the un-specalized Star Wars.

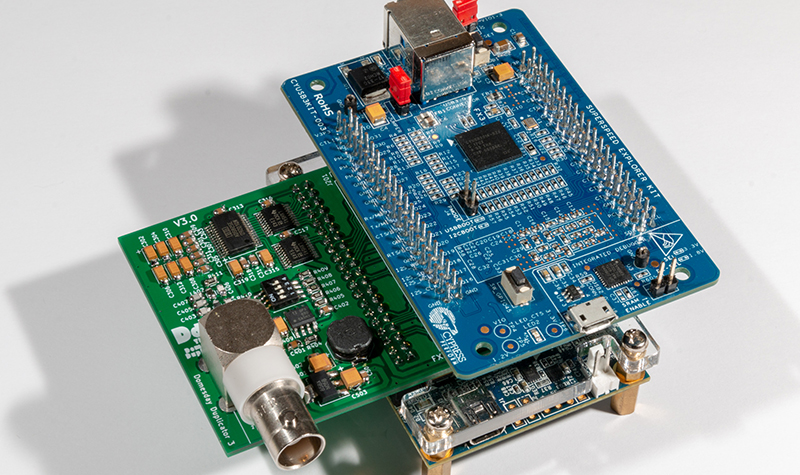

The Domesday Duplicator is a shield that plugs into an Altera DE-0 Nano FPGA board and a Cypress FX3 USB board. The Duplicator itself serves as an analog capture card complete with an RF amplifier and a 40 MSPS ADC — fast enough for any analog video signal. With the 50 Ohm input, it will work with most LaserDisk players, ultimately preserving this incredible historical archive from the early 80s.

Very cool. And I want one of those rips. I grew up watching SW trilogy on VHS every rainy day. I still have the tapes but they have gone through the VCR so many times the video quality is very, very poor. The VCR broke once and ate a few feet of ROTJ. I have to splice what I could salvage, and now it is missing about a minute and a half. The changes to the “specialized” versions make me angry, to the point that I just turn it off and watch something happier.

I wondered what was going to be done with the Domesday Disks – I’m glad someone has a good solution in the works.

As to the SW Laserdiscs, I have viewed DVD rips made from them about 20 years ago, and the quality of those is quite good. The Laserdisc versions are still the best ones made available.

There have already been a couple of archivals done. One is even web-accessible. On mobile at the moment, so no link.

The weak point is the laserdisc player. The rest of the hardware is easily accessible.

Here a word to search for in conjunction with the names of the movies in that trilogy.

despecialized

Wouldn’t it be said that analog will stand the test of time better than digital? The latter changes with formats, while writing which is analog is still readable centuries later.

It might still be readable, but would it be any more understandable? Everyone could see hieroglyphs, but it took a lucky stone (Rosetta) containing a know language to be able to understand them.

Any language digital or analogue needs to be regularly translated and transcribed to stay meaningful.And even then the meaning might be distorted over time because of errors.

Words are technically digital – as long as they are readable, a little dirt obscuring them does not change the meaning.

Yet, the meaning of some words has transformed over the years, and many words have multiple meanings.

Pretty amazing!

I have the Star Wars THX laserdisc set. Is there a good way to rip these?

It’s on my snarky bucket list to bring an old floppy disk or better yet mainframe tape to work. Next time a project sponsor says “I need to archive this data forever”, i’ll hand them said media and say – “No problem. Any idea how to read one of these?”

Sometimes dead tree scrolls are the better solution….

The current generation of LTO tapes (8) are designed to last for a maximum of 15 to 30 years in a temperature and humidity controlled archival storage. So forever is relative.

That’s pretty pathetic. Most ZX Spectrum games stored in someone’s attic still manage to work today, and that’s nearly been 40 years.

Yea, but that is like 48 KiB on an old audio cassette tape with the bits spread over like 5 minutes. A C60 tape (30 minutes a side) would be 88 meters (289 feet) of tape. So that would be about 15 meters (48 feet) to store 393,216 bits or ~26bits per millimeter (~683 bits per inch).

An LTO-8 stores 12 TB, and writes data at 360MiB/second, on a tape that is 960 meters long, so it is storing ~100,000,000 bits per millimeter (~2,540,000,000 bits per inch).

So not quite the same, even if you totally ignore that one has a tape width of 12.650 mm ± 0.006 mm and the other has a tape width of roughly 3.81 millimeters (0.150 inches).

The domesday book was seen at the time as the mark of the beast.

Ha. Someone writing down your name and counting your sheep.

What a breach of privacy.

I believe the man who gathered the names and livestock census in Wales was named Gwygyll.

I was part of the Domesday project back in the day, as a pupil at a small school in the Scottish Highlands (I’d add a link, but the ‘reloaded’ project has now closed). As the “computer kid” in my year (I was privileged enough to have a BBC B at home), I was given the task of inputting most of the data for our school.

Even then, at the tender age of 12 or so, I remember commenting that I was concerned about whether the content of the project would be readable in future years, compared to, say, the original Domesday books.

The images on the Domesday discs have already been archived in ‘best possible’ quality, by playing the original videotapes (from which the Laserdisc masters were authored) through a specially modified version of the BBC’s Transform PAL Decoder. I wouldn’t want anybody to get the impression that this project is somehow ‘preserving’ information that would otherwise have been lost, because at least in the case of the Domesday discs it’s not. For more details see ‘Preservation & Emulation’ at http://www.atsf.co.uk/dottext/domesday.html

The images – yes; the Domesday Discs – no. The Domesday discs are a combination of video, sound, still pictures, SCSI-1 data (EFM) and the data contained in the vertical banking which is specific to the laserdisc format. The duplication project is absolutely preserving information that will otherwise be lost. The Domesday system is the sum of all of the parts – not just a video tape.

Also the Domesday system is more than just the original Domesday discs; it also includes Countryside, Ecodisc, Volcanoes and more AIV compatible discs. All worthy of preservation (and not available from the videotapes).

Furthermore, only the laserdiscs are publicly assessable. The BBC and National Archives in the UK may have access to the original tapes, but they have systematically failed to make the Domesday system (paid for by the tax payer) accessible to the public. Even the ‘Domesday Reloaded’ project (which was only the community disc) has been taken offline.

Of course the Domesday system comprises more than just the video; my reason for singling it out is that it is the only ‘analogue’ content, and therefore cannot be recovered from the discs with anything approaching the quality of the original videotapes (and it’s the one aspect of Domesday preservation in which I had a hand). Incidentally I don’t see how being “paid for by the tax payer” has any relevance; very many things are so funded without the public acquiring any right of access!

Having high-quality copies of the original footage from the Domesday LaserDiscs is important, don’t get me wrong (and I’m aware who you are and that you have provided valuable (and highly appreciated!) assistance to recovering the original video footage)- but you can’t boot a Domesday system from it and therefore it’s not a preservation of the LaserDisc nor the Domesday system – and this is the ‘gap’ which the Domesday Duplicator project is filling.

You said ” I wouldn’t want anybody to get the impression that this project is somehow ‘preserving’ information that would otherwise have been lost” – and that is what I reacted too; because it’s not a true statement. There’s nothing here that devalues your previous work – in fact it’s quite the opposite – this will allow the possibility to merge the laserdisc contents with the high-quality footage in the future. It won’t be the original Domesday system; but DomesdayHD might be fun to see :)

You make no reference to the previous preservation efforts in the project description above, and the comment “ultimately preserving this incredible historical archive from the early 80s” could easily lead somebody to conclude that no such preservation had already been carried out. If you had acknowledged that the data gathered by the BBC had already been safely archived, I would have had no cause for concern. Perhaps you would consider adding a link to Andy Finney’s site so that the context can be better understood.

“You make no reference to the previous preservation efforts in the project description above” – The text above is a Hackaday article written by them about my project – I didn’t write it! Nor, did I ask HaD to write it (although I’m grateful that they did). If you were to browse the domesday86 website and look in the FAQ section for the duplicator sub-project – you’ll find reference to the BBC copy of the footage. I am only responsible for documenting my own work, not that of others. I still disagree that the Domesday System has been ‘safely archived’ though. That’s only true of the original video footage which is not the Domesday System.

The video (actually still images, including maps), text and index/navigation data have all been archived – basically everything needed to recreate the experience in the way Camileon did, or in the form that the National Archives now hold. What else is there?

Recreating the experience in the way that the Domesday system did?

Recreating the experience for all of the AIV discs supported by the Domesday system?

I could go on…

I have to say, I don’t really get your ‘job done’ attitude to this. Camileon caused the BBC to rethink how they archived the original video footage, but the project itself didn’t really achieve much in terms of publicly usable output (or any other output of note come to think of it). I certainly don’t subscribe to the approach that we should just “trust the BBC to get it right”. Many copies… many mediums…

I have never suggested that there’s ‘nothing more to do’, but you seem to want to erase the earlier preservation efforts from history. If Camileon demonstrated anything, it was that attempting to reproduce exactly the original Domesday experience, warts and all, is not particularly worthwhile. Presenting the information in a more modern format on a more modern interface (and at the highest quality) was seen as the way to go, and that is what the National Archives now hold. It might be desirable if it was more readily accessible to the public (as it was for a while online), but I don’t see how you can claim that any significant Domesday-specific content has not already been preserved.

I don’t wish to suggest that your work is not worthwhile, nor that having another backup of the Domesday data is in any way undesirable, but I still feel that the context of the earlier preservation work is important. Of course your project may well be of great benefit to other interactive video discs, playable on the ‘Domesday system’ but not otherwise connected with the project.

” If Camileon demonstrated anything, it was that attempting to reproduce exactly the original Domesday experience, warts and all, is not particularly worthwhile.” – I couldn’t disagree more strongly. Preservation is “the act of keeping something the same” (according to the Cambridge dictionary at least).

I still don’t understand where you get the impression that this project (or my actions) are an attempt to “erase the earlier preservation efforts from history”, but you are welcome to your opinion.

I think we’re just going to have to agree to disagree. As an open project, Domesday86 doesn’t require anyone’s agreement or endorsement other than my own in order to continue (actually under the GPLv3, it doesn’t even require mine); so I’m not concerned if some people don’t share my vision; I know of plenty of others who do.

Archived in ‘best possible’ quality? Unfortunately i’m not quite sure.

In 2003, the original tapes (1”C reels) have been duplicated twice on two different new tapes formats:

– On D-3 uncompressed composite digital tapes first.

– Then these D-3 tapes have been duplicated again to Digital Betacam compressed component digital tapes.

It’s seems a little odd to have used an intermediate D-3 format, adding a copy generation for no obvious useful reason, and also considering it was at that time already an old (1991) and rather obsolete format. D-3 player were complex and costly, and difficult to maintain: the BBC was able to preserve only about 1/3 of their D-3 tapes because it was not possible even for them to maintain enough working players to read them all.

Then, these D-3 tapes have been duplicated to Digital Betacam tapes using a special and interesting PAL decoder. The use of this PAL decoder is a very good thing, but using Digital Betacam is less clever. First it is a compressed format (light compression, but compressed anyway). And it is a digital format on an unreliable magnetic media.

They say “Even if we have to go to a special facility to use a DigiBeta machine in 2020, it is a good bet that there will be one to use. It is fair to say that 2-inch monochrome quadruplex videotapes, which could be almost 50 years old, can still be replayed somewhere today, which would give ‘us’ until 2050 to transfer the digital information onto a newer format”. Unfortunately, what it is true for old analog tapes is really not true for newer digital ones.

It is well known that even 30 to 50 years old analog tape formats are much more reliable and forgiving than digital tape format (except may be Betacam SP): analog tapes are still playable, even if they exhibit some defaults like noise in video and sound, or drop out lines.

10 or 15 years old digital tapes are unfortunately already difficult to read correctly (especially if stored in bad environments and if cheapest brands like Emtec or Fuji have been used) and are producing much more visible macroblocks or freezed pictures defaults, and very audible defaults in sound. And also, highiest data density means more extensive loss of data with every single damage on tape.

Most old analog VTR are also easier to “restore” because they use simpler electronical and mechanical parts, where most recent digital VTR are using highly integrated, very specialized chips (manufactured or programmed only specificaly for a VTR model, and impossible to source or clone) and high precision mechanical parts (much more difficult to replicate). The later VTRs are already very difficult to be kept working only 25/30 years after their creation (like the D-1 or D-3 formats), where 40 or 50 years old VTRs are still working today.

If i were them, i would have digitized directly the original 1” tapes directly to uncompressed or lossless compressed files, using the same special PAL decoder. Then i will have kept several copies of these files onto different media (hard disk, DLT and LTO tapes for example), and took care to duplicate them every 3 to 5 years (considered by most of archive specialists as the time frame allowing easy and default free reading).

It could be possibly better to try to re-read and digitize original 1”C tapes today rather than D-3 or Digital Betacam ones…

You make a number of interesting comments. I will try to reply to as many of them as I can:

> It’s seems a little odd to have used an intermediate D-3 format, adding a copy generation for no obvious useful reason.

It is misleading to think of it as “adding a copy generation”, rather it is ‘preventing further degradation’. By transferring the material onto a digital format you protect it against gradual deterioration in storage. D3, as with all digital tape formats, has error correction so that – so long as you can play the tape at all – it should ensure that the quality remains identical on replay to what it was when originally recorded.

> the BBC was able to preserve only about 1/3 of their D-3 tapes because it was not possible even for them to maintain enough working players

I don’t believe that is true at all. Where did you acquire that information?

> First it is a compressed format (light compression, but compressed anyway). And it is a digital format on an unreliable magnetic media.

DigiBeta was the most appropriate medium available at the time, and the compression loss is insignificant. Even today, ‘magnetic media’ is the only form of digital storage with a sufficient capacity for archiving.

> It is well known that even 30 to 50 years old analog tape formats are much more reliable and forgiving than digital tape format

It is of course important that archived digital material be copied onto a newer medium before it has had a chance to degrade in storage (to a point where errors cannot be corrected). But so long as this is done diligently digital data can be preserved indefinitely with no degradation whatever, and without the need to be able to play obsolete media formats. No analogue format can compete with that.

> If i were them, i would have digitized directly the original 1” tapes directly to uncompressed or lossless compressed files, using the same special PAL decoder.

It wouldn’t have made any difference, because it’s just one analogue-to-digital conversion in each case (the Transform PAL Decoder is entirely digital, of course). The data entering the PAL decoder will have been identical to the data leaving the ADC when the 1″ tape was originally played, but by digitising it some years earlier any further degradation of the analogue medium (and the need to maintain obsolete players) is avoided.

Thanks for your reply. It is very interesting to discuss with you, especially since i’m a big fan of BBC work in preservation and R&D (i would love to visit them one day). And I hope you take no offence at my “geeky” comments!

> It is misleading to think of it as “adding a copy generation”

Not really. Yes, first link between 1″C and D-3 is analog then signal is converted to digital by D3 VTR. But, if i understand well, it is then converted back again to analog to output to go into the PAL decoder and then digitized again and compressed to be recorded finally on Digi-Beta. So there are really multiple analog/digital and digital/analog conversions, so multiple generations.

> By transferring the material onto a digital format you protect it against gradual deterioration in storage. D3, as with all digital tape formats, has error correction so that – so long as you can play the tape at all – it should ensure that the quality remains identical on replay to what it was when originally recorded.

> digital data can be preserved indefinitely with no degradation whatever

This is the common belief about digital format. It is rather true in computer domain, but not so much for video media.

First because video storage medias are much more prone to error and damages than computer/data ones, and second because error corrections are rather poor and unefficient.

Try to store data to an LTO tape, a DVD or an HDD: it will very reliably play back with a guaranteed 100% data accuracy the very most of the time, and an LTO tape is quite rarely damaged (except of course scratches is you mishandle DVD, or use very cheap and low quality DVD). You will usually never have any modification of the original data because of error corrections.

Video devices are much more prone to error or damage (you can have read errors even on a brand new tape), especially compressed format one, and errors are “corrected” by replacing damaged blocks of data (ie blocks of picture because of DCT compression) by some kind of more or less approaching pattern. So the resulting corrected pictures are really not identical to original ones. May be D-3 error corrections are better than Digi-Beta, i’ve never used any so i can’t personnally tell.

It is worth to mention that Sony did try to use its Digi-beta tape format has a data storage: DTF and DTF-2 formats. This was a complete failure because of the unrealiability of this tape format. A brand new tape, recorded in a brand new recorder was able to exhibit read errors at the first read! And since it was this time data, read error was meaning lost file! Sony has stopped developped DTF only after a few years.

> the BBC was able to preserve only about 1/3 of their D-3 tapes because it was not possible even for them to maintain enough working players -> I don’t believe that is true at all. Where did you acquire that information?

http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/bbcinternet/2010/08/safeguarding_the_bbcs_archive.html : “There are over 340,000 tapes in the D3 collection and it was used throughout 1990s up to 2005 as the analogue terrestrial delivery format. It is no longer mechanically supported by the manufacturer so 100,000 tapes were selected for digitisation.”

http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/rd/pubs/whp/whp-pdf-files/WHP167.pdf : “The BBC Archive holds around 315000 D3 tapes. The D3 Preservation Project aims to transfer around 100000 of these tapes to MXF files over a six year period starting November 2007.”

This documents also reveal that they decide to use analog PAL output to an analog to digital PAL decoder rather than direct digital SDI output.

> DigiBeta was the most appropriate medium available at the time, and the compression loss is insignificant. Even today, ‘magnetic media’ is the only form of digital storage with a sufficient capacity for archiving.

I don’t think DigiBeta was the most appropriate, because, as i said before, it is much less reliable than computer data tapes. And also because DigiBeta use 4:2:2 sampling (discarding half of chroma samples) and slight compression. So losses are really not that insignificant.

If the goal was to archive in “best possible quality” I still believe that it would have been better to digitize directly to file, using uncompressed 10-bits format, and then store copies onto various digital DATA media like LTO. And then re-generate new 100% accurate data copies every few years, rather than error “corrected” video copies.

My own company ( https://www.geckoandco.com/ ) has digitized about 16.000 video tapes (consumer and professional and analog or digital ones)/40.000h during the last 8 years (and much more than that when i was working for other companies before). And most of them where for INA (Institut National de l’audiovisuel = french National Audiovisual Institute). So i can personnally tell about DigiBeta or other formats quality and reliability.

It would be interesting to hear more about the techniques and the processes you use when you digitize old/obsolete media. It is a good topic for a Hackaday article, that is for sure.

I can also imagine that there would be a few useful tips for the amateur digital/analog archivists out there

No, there is only one analogue-to-digital conversion in the entire process, which is when the 1″ tape was recorded onto the D3; after that everything is digital. I stated that playing the 1″ tape (even in perfect condition) into the PAL decoder would have given no different results.

Whilst that may be true, it doesn’t mean that there is any significant loss. Rather it means that whilst the error correction may not restore the precisely identical set of bits (it usually will) any difference should be invisible. It is still far better than keeping the analogue tape and hoping you will be able to play it (and not damage it) years later. Once it is in digits, you can make as many copies as you like and even transfer it to a genuine data-storage medium. But the key thing is to get it in digital form as soon as possible (so long as you can do so ‘losslessly’).

That comment is meaningless because D3 is already ‘digital’! I’m not even sure it is referring to the bulk D3-to-DigiBeta transfers that the Transform PAL Decoder was used for.

AFAIK no technology was available at the time to capture the real-time video data to a computer storage medium.

This is not relevant when the source is PAL, which has even lower chrominance bandwidth.

Pragmatically the method used gave the best possible results and the least risk of degradation or damage of all the methods that were practical and available at the time.

> … after that *everything* is digital

You mean that the Transform PAL decoder was using SDI input and output, not composite or components ones? So my bad, i thought it was using analog PAL signal. And i must say also that i didn’t know that SDI SMPTE 259M-A was able to transmit composite PAL, sampled at 4fsc (also used for D2 format). Thanks for making me learn something new!

So i do agree that in this case there’s no additional loss using an intermediate D3 format, beside the possible loss of read error corrections (but i also don’t know how the D3 handles corrections compared to DCT compressed formats).

> it means that whilst the error correction may not restore the precisely identical set of bits (it usually will) any difference should be invisible.

For D3, maybe, i don’t know. But for Digital Beta, I would not say that macroblocks generated by read errors (channel conditions) are “invisible”. And unfortunately they happen quite easily and often with Digi-Beta.

> It is still far better than keeping the analogue tape and hoping you will be able to play it (and not damage it) years later.

Except if digital tape is finally producing too much read errors after 15 years of storage, introducing new digital defaults to the video. Maybe the older 1” tapes could be always correctly readable, with no or little more damages than 15 years ago. We can’t guess… But i quite often had to read very bad 15 years old tapes, so i know it can be a real nightmare with very poor and deceiving result. I hope it will not be for you.

> That comment is meaningless because D3 is already ‘digital’!

This is not a comment from me but a citation from BBC website. But i agree that instead of “digitalisation”, they should have said “transfer”

> I’m not even sure it is referring to the bulk D3-to-DigiBeta transfers that the Transform PAL Decoder was used for.

It seems it is. The BBC white paper i’ve linked to states that they used a “Transform PAL decoder”, and that “The D3 VTR outputs a 4fsc digital composite PAL signal and the transform PAL decoder converts this signal into a digital component signal”. So if the “Transform PAL decoder” you’re talking about is the one inputing 4fsc composite PAL SDI signal and outputing 4:2:2 component SDI, it seems to be the one used for these tranfers.

> This is not relevant when the source is PAL, which has even lower chrominance bandwidth.

For me, analog chroma bandwidth and digital chroma samples decimation are different things and not directly comparable. Bits depth (8 bits here) is more easily comparable, and usually 8 bit is considered equivalent to analog chroma bandwidth. But then discarding 2 chroma samples out of 4 = halving the chroma resolution is loosing details compared to continuous analog signal.

So Digital Betacam does introduce -some- losses becauses of 4:2:2 sampling, and 2.34:1 compression ratio, plus additional ones in case of macroblocks due to read errors.

> AFAIK no technology was available at the time to capture the real-time video data to a computer storage medium.

Not possible in 2003? I thought it was already possible and used mainly for motion pictures post-production. But may be not yet, i don’t know.

But it is now easily possible to capture 8 bits 4:4:4 uncompressed to file. So the best quality would probably be achieved by capturing ASAP from D3 tape to file instead of from Digital Betacam tape. But only if possible to find today a good working and not too worn D3 player, and if D3 tapes are still correctly readable 15 years later. But since PAL decoding with Transform decoder has been done only AFTER D3 recording, decoder should also be used during this capture.

And don’t get me wrong:

– Transform PAL decoder seems to be a really great device. I don’t know if it is better than some other advanced 3D PAL decoders (from Snell & Wilcox or another brand i can’t remember).

– Digital Betacam was a very common format for mass archiving/preservation, since it was a good compromise between cost and quality, and extensively used. But for very rare and precious archives, it was really not the “best quality possible” choice. D-1 would have probably better quality (but also difficult to read nowdays).

– So all in all, if Digi Beta tape can be read without errors today, overall quality will be very good, but not “perfectly perfect” ;-)

– Maybe D-3 and Digi-Beta should have already been duplicated and captured years ago to mitigate the risk of read errors because of aging tapes.

Thanks for this pleasant and instructive discussion, i like to exchange like this with open minded people :-)

> You mean that the Transform PAL decoder was using SDI input and output, not composite or components ones?

It’s a PAL decoder, so by definition the input is ‘composite’ and the output is ‘component’. But it’s fully digital of course: one does not build analogue video processing equipment these days. ;)

> Except if digital tape is finally producing too much read errors after 15 years of storage

As discussed, digital archives must be regularly transferred to a new format.

> Maybe the older 1” tapes could be always correctly readable, with no or little more damages than 15 years ago.

Attempting to keep a unique tape in pristine condition, and then play it (possibly having just the one chance) in an ancient player which is just as likely to shred the tape. It’s not my idea of good archive practice!

> It seems it is.

The transfers I know about were to DigiBeta tape, not MXF files (and it was the entire archive, not a subset, AFAIK).

> For me, analog chroma bandwidth and digital chroma samples decimation are different things

Nyquist would disagree (and so would I)!

> But then discarding 2 chroma samples out of 4 = halving the chroma resolution is loosing details

> compared to continuous analog signal.

If done properly it theoretically discards nothing. This is basic sampling theory.

> But it is now easily possible to capture 8 bits 4:4:4 uncompressed to file.

It’s pointless and wasteful to save 4:4:4 if the source was PAL. 4:1:1 would probably be adequate.

> Transform PAL decoder seems to be a really great device. I don’t know if it is better than some other

> advanced 3D PAL decoders (from Snell & Wilcox or another brand i can’t remember).

S&W performed a comparison: the Transform Decoder was better than theirs (but also much more complicated, and with a large latency).

Hello Richard,

Since we’re on Hackaday, may be you could write an article about the conception and in-depth technical details of your “Transform PAL decoder” ?

And also, have you consider to open source it ?

It’s not “my” Transform PAL Decoder, it was invented by Jim Easterbrook at BBC Research & Development (I ‘simply’ had the task of implementing it in real-time hardware!). You can read all about it at http://www.jim-easterbrook.me.uk/pal/

I’ve read Jim Easterbrooks’s website. But i would love to know how you have implemented it. And open sourcing it could be useful too.

My implementation is described in BBC Research & Development Document No. 1859(02): ‘Transform PAL Decoder CD3/568 Handbook’, however this is not a publicly accessible document. As regards “open sourcing”, bear in mind that it’s not software: the design exists primarily as circuit schematics and Abel files. However (and this has previously never been published) I’ve put the block diagram at http://www.rtr.myzen.co.uk/CD3_568.jpg

it’s perfectly possible to ‘open source’ hardware (the Duplicator design is a good example). I’d recommend the Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 license – but there is good guidance on their website around what the different licenses mean. Details of the design would be very useful for the ld-decode project that performs the opposite task of the duplicator (transcoding the RF image back into video/sound/etc). ld-decode is also an open-source project:

https://github.com/happycube/ld-decode

It’s not my hardware, it is the BBC’s hardware! I have no rights to it of any kind, and even publishing the block diagram strictly violated the BBC’s copyright. Information of the kind you seek is only obtainable from BBC Research and Development at http://www.bbc.co.uk/rd/

It seems that Jim Easterbrook has kindly published his 2D Transform decoder under the GPL, so it should be possible to analyse the implementation (even without the BBC documents) – the implementation is in Python:

https://github.com/jim-easterbrook/pyctools-pal

I saw that Github, but i’m unsure it is the complete algorithm used for the hardware decoder, since on Github it is described as “2D Transform PAL Decoder”. But on its website, Jim Easterbrook says: “Using computer simulations of the transform PAL decoder algorithm I’d been able to show that three-dimensional processing was vastly better than two-dimensional, and I’d been able to experiment with different block sizes, window functions and so on. However, I’d not been able to process more than a few seconds of carefully chosen test material. I did wonder if a software version of the decoder might have an application in extracting high quality stills from composite video, but it was clear that real-time hardware would be needed to meet the requirements of our most likely “customer”, the BBC archives.”

So i wonder if the hardware decoder is implementing a 2D or 3D process?

The hardware is 3D (which accounts for the complexity and long latency) as you can see from the block diagram – there are X, Y and Z transforms. I expect the reason Jim decided it was OK to publish a 2D software version is because that’s not what was used in the hardware decoder (although I think you can switch it to that mode for demonstration purposes). The other mode the hardware can be switched into is the one that was implemented specifically for the Domesday material (3D but with only a 2 field temporal aperture for still frames), to bring us back on topic.

Data is like that, so take a lesson from nature, keep replicating the data (DNA) to new platforms, use error correction, and keep the data in more than one place.

Procreation.

In 1990-1991, Micheal Cranford and I, working for Tektronix, Inc., built the model FC511 HDTV Format Convertor under contract with the Advanced Television Test Center. It accepted analog Y, Pr, Pb video, digitizing it at just shy of 75, 37.5, and 37.5 MSamples/Sec. The 8 bit Y, Pr, Pb samples were then fed to a Sony HDD-1000 DVTR. Upon playback, the signals on the tape were then converted back to analog for viewing or for providing test material for the various HDTV encoding schemes that were competing for approval as standards for the U.S. and Canada. Several FC511s were built and were instrumental to the development of the current HDTV standard.

This is another fascinating story that would deserve an article here on hackaday!