Today I don’t have a hack for you. I have a story, one that I hope will prove useful to a few of you who are considering a move to Asia to chase opportunities here.

Seven years ago, I was a pretty stereotypical starving hacker. I had five jobs: A full-time dead-end job in biotech, and four part-time or contract gigs that were either electronic hardware design or programming. I worked perhaps 50 hours a week, and was barely past the poverty line – I was starting to wonder why I spent so much time in school. I saw the economic growth in Asia as an attractive but risky opportunity.

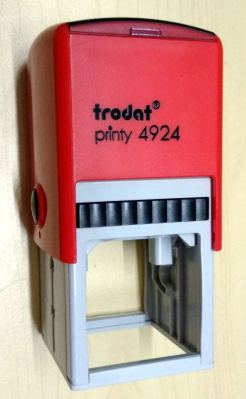

Check out that image above…France? No, this is Shenzhen and let’s face it: many exciting things are made there (even the copies). After a short visit to the region, I decided to take that risk but not in Shenzhen. I sold everything I owned and moved from Canada to Vietnam and started a company. Over the last seven years things have worked out well, although I certainly wish I had known more about the process before I got on a plane. This article is about the general path I took to get where I am. Obviously I don’t know the legal framework of every country in Asia, but speaking in generalities I hope that I can cover some interesting points for the curious and adventurous.

The first thing to say is that establishing yourself in another country is hard. My grandparents moved to Canada from Poland in the 1960’s with essentially the clothes on their backs, and without a working knowledge of English or French. I always listened to their stories and admired them for their perseverance. Perhaps there is someone like that in your family, and maybe you’ve admired (or rolled your eyes at) their stories. The fact is though, their tales of hardship are not only probably true, but they’ve spared you the worst of it.

Before You Leave: Sorting out Finances

To avoid a little of that hardship, the first step towards moving to Asia is preparation. We can divide that into two categories: financial and personal. On the financial end, you’ll need a little money. I would say a reasonable minimum is living expenses for a year in your destination, plus any amount needed to set up a company (do some preliminary research). If you plan to keep your foreign bank account, give someone you trust power of attorney over it. Banks are fickle creatures, require that you show up in person to do a number of things, and having a legal representative in your home country costs nothing and can save you a world of pain.

Next, take some steps to prevent identity theft. At the very least make sure that any official documents are being mailed somewhere safe. I was quite careful about this, my identity was still stolen, and it was quite a pain to sort out. Hopefully you will have better luck.

Then it’s time to think about taxes. Chances are you’re not going to make much (or any) money in the first year, so if you’re eligible for an income tax refund from tax paid at your last job, you can work out the optimal time of year to move.

Before You Leave: Sorting Yourself Out

On a personal level, first and foremost you’ll need to have a skill set that is realistically in demand, preferably something that is possible to do remotely. This lets you potentially operate as a freelancer or part-time employee (depending on labor laws) in a sector related to what you want to do while you get the hang of things. Web development or digital marketing are common choices, and while viable, be advised it’s a crowded market for those things here, and scale your salary expectations accordingly. Teaching English without full qualifications as a teacher in your home country is unlikely to build a professional network in the tech sector; my strategy was to avoid it completely, and I think that was the right choice.

Next up is avoiding errors in mindset. Probably the single wisest thing I did was to see myself as an immigrant: that means working harder for less money, and being cautious of being taken advantage of. This is very different from the attitude I occasionally encounter at different ‘expat’ communities in Asia. I want to keep this article positive, so I’ll leave it at that.

It also wouldn’t hurt to read our some of Hackaday’s Life on Contract articles. Many of us are (or have been) working as contractors in the hardware or software world and have contributed to this series of articles. The advice there has helped me more than a few times.

That brings us to the next point: Make sure you love your job, then structure your life to accept longer working hours. Nine-to-five isn’t really a thing in Asia, for reference I work 60-80 hours a week and take about one day off a month. I realized that if I treat my business as a hobby it would remain one, and I committed to putting in the hours to get it off the ground. To my surprise, I have at no point felt healthier or less stressed – working every day means that there are always exciting opportunities to seize, and enough hours to do so with both hands.

Finally, you’ll want to learn enough of the relevant language and culture before you arrive to not be a jerk. It’s easy to learn more once you arrive, but sort out the basics before you get on a plane. While I speak very basic Vietnamese, in hindsight I regret not spending more time learning the language before everything became too busy.

Finally, You’ve Arrived

You’ve arrived, and taken a few weeks off to tour around and get the hang of things. Now you’re ready to get to work, and wondering where to start. This is where I suggest something that is occasionally considered controversial by locals and foreigners: open a company, become a legal resident, register with the tax authority, and obtain a driving license. What type and structure of company you open depends on many factors and is beyond the scope of this article, although I opened a limited liability company with myself as the sole owner.

While many people have told me it was unnecessary, and I could just illegally work and avoid tax, there’s a reason that’s unrealistic. Simply put: a legitimate company gives you access to instruments that let you scale.

No one will be willing to sign a significant contract with you unless you can legally enter that contract, issue an invoice, and have some liability for the work being completed once payment is issued. Not to mention if you ever become even moderately successful, you’ll be big enough to be noticed, caught, and deported.

The exact method to do this varies by jurisdiction. A good way to start (if you are in a communist country) is to read the five-year plan or a summary of it. Do any of the sectors outlined in the plan touch on aspects of your business idea or skillset? If so, you may be able to get some benefit upon opening a company licensed in that area. Examples might include significantly reduced taxes or required starting capital. I was able to do this, and it helped considerably.

Next, network at co-working spaces, explain what you want to do, and ask for a reference to a lawyer. I’ve seen legal fees vary by a factor of five for opening a foreign-owned company, depending on the size and specialization of the law firm, so a referral to the right lawyer will save you a lot of money when you need to do something so straightforward. Explain to your lawyer what you want your company to be able to do, and ask if there are any government programs (e.g. tax breaks) you can take advantage of. Before you pay any significant money, ask them to quickly explain how you can get legal residency as a company owner and make sure you can go through the process.

In several Asian countries, companies are only allowed to operate within the sectors of the economy they are licensed for. In this case, always add consulting to your business license – unexpected opportunities will come up and this will allow you to take them on within reason. As part of the company registration process, you’ll receive a company seal or stamp. Do not ever lose or damage this as it is your company’s legally binding signature.

Your lawyer will also be able to tell you if you’re legally required to rent a specific type of office, and connect you to an accountant. You will need them for tax compliance at least, but only for 2-3 hours a month so the price must reflect that.

Your new accountant will be able to register you at the tax authority, and help you learn how to issue legal invoices and contracts. Make sure to get at least a bilingual service contract and employment contract.

Finally, call a travel agency and ask them to get you residency. You may have to jump through some strange hoops, just do it patiently and insist on getting a legal invoice from the travel agent and paying taxes on it. Some are shady with regards to visas and residency so you want that paper trail! Your travel agent will also very likely be able to instruct you on how to get a driver’s license given your new residency. In my opinion, enjoying motorcycles (responsibly) is one of the great joys of Southeast Asia, and a license is also a useful piece of ID. The ones from your home country will one day expire and become difficult to replace.

Congratulations, You’re a CEO and a Resident

With what you have now, it should be relatively easy to open a company bank account. If you live in a country where there is no company owner’s draw, be aware you’ll likely need to open a personal account too, and issue a work contract between you and yourself to pay yourself between your accounts (not as confusing as it sounds).

With that done, your life is now immensely easier: you can use your company to enter into contracts. Not only does this let you operate confidently as a freelancer, it means a lot of services that are not typically available to foreign residents just became available to you, because you can operate as a local legal entity via your company.

At this point it may be a good idea to print business cards. Co-working spaces can normally help you with this, although you can also hire a designer if you need a logo and so on. Exchanging business cards is still somewhat of a ritual in Asia, so get yours designed and printed properly, on reasonably thick uncoated paper.

Networking: Learn It, Love It

Next is the part that I completely failed to do, and struggled for a year as a result: networking. I used to consider networking events useless, and just worked hard for my existing clients and developed technology I thought I would need later. What I missed out on were more interesting projects, and companies willing to pay me significantly more to do them. I literally went out to one networking event and not only doubled my company’s gross income, but found far more exciting work. The obvious lesson here was that I didn’t have to go to these events regularly, just once in a while to make sure I’m being paid market rates and working on the right projects.

With that you should be able to operate. Looking back, I’d say that the two most important things are to avoid participating in corruption and bad habits, and to cultivate a measure of stoicism. Asia offers a lot of distractions and legally-gray shortcuts, ignore them all. Focus on what you need to do to succeed, do it legally and well. If you’re in a developing country, a few truly terrible things will probably happen too. Deal with them stoically and get back to work – then if it makes a good story, save it for your grandchildren.

You’re able to do hardware design, programming, and something that the bio-tech industry needs, and yet you were living near the poverty line?? I don’t understand how that happened.

Also working 80 hours a week and only giving yourself one day off a month doesn’t sound like much of an upgrade.

I hope he doesn’t have a family.

I seriously dont understand how. I mean, i worked in a start up commercial makerspace for the absolute lowest wage allowed by the government, and while not wealthy, the side gigs made it quite doable…

Welcome to the new middle-class. Working for the-man, vs working for oneself.

No, I don’t think that’s it. Engineers get very nice salaries, much much higher than the poverty line.

It depends on the location.

Some places have very high cost of living.

True enough. But still, an engineer working five jobs, yet “near the poverty line”?? Where would that happen?

In in the US just don’t live in the bay area or the east coast and you’ll be fine.

Also, Chicago.

And health insurance, which can be a rather large portion of your income.

An engineering in a HCOL location is typically pulling down 6 figures. I don’t care how expensive things are, you are nowhere near the poverty line…

Don’t forget, this is in Canada. I used to work for RIM with a very nice salary, but that all changed after 2002. If you want to make a living in Canada, forget about hardware design, especially if you are over 35. New graduates are different story. But once they reach about 35 it is either move up to management or move through the out door.

I’m not anything personal about you, just using your comment to say something I don’t believe I ever heard or read. In capitalist and socialist economies we are free to move about when it comes to employment. When you work for the man you are working for yourself, because you are working for yourself. Even if there is a a contract signed, there is an implicate contract. That we as an employee will do what we were hired to do, and the employer will live up to what they promised as compensation. Sick leave, and vacation time,health insurance are compensation as much as salary and wages are.

“free to move about” pfft. Most people *aren’t* free to move about unless they’re already making enough money to afford not to work for a while when that “move about” fails to deliver. If a person is barely making ends meet they can’t afford to move. They can’t afford to lose health insurance. If they have a family they’re doubly screwed in that regard.

this has captured my curiosity as well! i see two possibilities: “dead-end job in biotech” means answering phones and the consulting side-jobs were essentially volunteer or speculative work for non-profits or friends. or “poverty” means “wealth”.

i’ve made being chronicly underpaid into a career path and i’ve never been anywhere near the poverty line.

come on sean, there’s some sort of misdirection here and we want to know which way it was going

OK, I can see one misunderstanding in the comments (not you specifically) — please note I did not formally study engineering! I studied biology — an undergraduate degree with more molecular biology and a thesis program focusing on natural resource management. My engineer friends also struggled to find steady work out of school at the time (there was a lot of work-sharing arrangements), but they were able to secure reasonable salaries after some time. Many of them also had to move, but not quite as far.

Dead-end job in biotech does literally mean answering phones most of the day. While I worked alongside some fine people there that deserve my full respect, it was very much a glorified call center. I didn’t think those details were interesting for the purposes of this article though. To me, what was important was that I was dissatisfied with my job and I needed to do something I thought was more rewarding with my life — even if that meant a lot of work.

The mechanism I used to do that was immigrating to Vietnam, and at the time there was more or less zero information online regarding the process I went through, or what I could expect life to be like. That’s more what I was trying to share here, and in hindsight it was an error (as a writer) to discuss any details of my employment in Canada as that has nothing to do with the message I’m trying to convey.

We have the same problems in America the only difference is we are in Debt for school that we can never shake.

I have met many people with bachelor degrees in highly specialized fields, that work at Home Depot or Wal Mart.

While the companies utilize the same tricks they do in Canada.

It’s good to know that Canada’s government is just as corrupt as the U.S

Well Bob,

Canada has embraced multiculturalism to the extreme, but most immigrants don’t care about their own racism that comes with a damaged person. Our university technical and medical programs are well over 90% filled with south-east Asians and poor US students with economic-migrant-papers/student-visas (very skewed anomaly that under-represents domestic demographics). That dream of getting a degree and migrating again to become a US taxpayer is still very real. It is considered taboo to talk about this issue, as there are institutional economic incentives to overcharge these students tuitions in a futile attempt to offset the taxpayer subsidies.

You may be tempted to say “Oh, you must be a ___”… but you would be wrong… we have had mass shifts in cultural norms since Quebec has offered rich Chinese investors golden-passports for the past 30 years. Basically, if you and your spouse invest $800k dollars each, than you get the coveted Canadian passport (valid in most places except the UAE). The French have a fine tradition of being more xenophobic than Arizona, so most of these economic migrants usually move to more progressive urban centers where there is a community that offers their own languages and cultural resources.

Asian traditions usually mean that you live with your parents until you are 30, and buy a home when it is time to find a wife. However, due to the prevalence of everyone investing in real-estate with little controls, the rent-seeking speculative investors would flip the same properties several times a year to try to launder their money out of Communist China (only very recently did this slow down due to China Policies). This market activity attracted holding company funds from all over the planet with credit amplification hacks, and magnified the home ownership costs out of reach of most residents.

Now many urban areas with universities have a manufactured shortage of housing, over-supply of standardized talent, and a bias to undervalue themselves due to a cultural barrier. Many companies run by questionable individuals will tend to either underpay relative to global norms knowing migrants will take the deal, directly exploit migrants due to language barriers, and or exploit youth employment tax credits by churning staff every 3 years. Thus, if you can do long-term financial math than you are out of luck finding domestic work in technology.

So as an Engineer it is completely believable that you would be unable to sustain a working career in Canada, as most realize an advanced degree is sometimes just proof of our naive assumptions about how the real world works.

I am sure there will be a dozen exceptions to this trend, but this is what I have witnessed domestically.

Wow, that’s quite a dissertation.

Sean Boyce was working five jobs. It doesn’t matter if he has an advanced degree; he should be able to provide plenty of evidence (and references) that he knows his stuff.

If an engineer can’t make a living, what is the plight of the average person? If an engineer is living near the poverty line, then I’d expect 95% of the population to be in poverty. That’s not the case in Canada, so regardless of the arguments you present, something doesn’t add up.

It is quite foolish to generalize, as it opens the door to ugly detractors:

However, the situation is very similar to what happened in silicon valley, where a $140k/year currently equates to the living standards of a minimum wage job in other communities. The standards of living simply drop if a majority of dual income homes can’t really afford a mortgage without bidding down the liquid capital invested back into the local economy. In mathematical terms, if over 28% of your household income (in deflationary dollars) is spent on housing, than your family will always be poor and never understand why. Now that sub-prime mortgage derivatives are back thanks to Trump, even those with a distorted understanding of their current invested equity are again uncomfortably exposed to global market fluctuation risks like in 2008. Taken from another perspective, deflationary-dollar household incomes in North America have been flat-line for 20 years despite optimistic employment number rhetoric, and the costs of living have steadily increased to drop people below what was considered middle class. Canada is 1/10 the size of the US with a higher tax burden, and shows this financial strain much more readily in the publicly available census data.

And Bob, talent does not equal proportional-pay unless a worker can actually leverage their own market scarcity. You should take the $60k/year pay-cut and try to live here for a year if you still don’t understand.

I know of several electronics/engineering businesses that had over 150 employees and had been well run for over 40 years either go under or, for the wiser ones, leave Canada, or have been bought up and moved out of our country.

A firm I had a nice contract project with is one of them. They were bought up by another non-Canadian firm, and within 3 weeks over half the engineering staff has been let go. The project I am involved with is now being well documented only to leave Canada finally and completely in a few more weeks. Another Avro Arrow of sorts; designed here, but we can not benefit from it.

Frankly, I found my low salary confusing as well. In hindsight, I think three main factors played a role: nationwide cuts to science funding meant choosing the private sector over academia or government work. Private sector work was very focused on pharmaceutical research in my city, which at the time had an influx of overqualified applicants (salaries were very low as a result), and then changes to drug patent laws bankrupted most of the pharma research companies in the country and they moved overseas.

I was not even the only person in my department with a MSc from a good university making under 25,000 a year — that’s gross income, CAD not USD. No benefits either. I took the less drastic step of looking for a new job before deciding to move, but after a year I decided to take the leap.

Oh wow, that indeed is a shitty wage. I stand corrected. Thats only marginally above minimum wage here in the netherlands.

$25,000 CDN??? WTH!?! That’s like $12.5/hr. That IS minimum wage. And with a MSc as well. You probably would have got more working at McDonalds or Starbucks. Stuff like this makes me sad/mad. I usually ignore when a burger flipper whines about making minimum wage, doing a half ass job with out any real marketable skills, but someone that put an effort into getting an education and so forth, we have a real problem on our hands. (Yes run on sentence, oh well)

Sean, I hope your happy in your new path. You recognized a problem and you dealt with it your way. It’s all anyone can really do. Wish you luck in the future.

These videos cover quite a bit of what’s needed to move to China.

https://www.youtube.com/user/serpentza/videos

+1

https://youtu.be/sx23lb06Hl0

I’d say if you’re doing that much work and near the poverty line, you’re severely undercharging your customers. Especially 7 years ago back before you could buy nearly any dev board for under 10$.

Yes, this was one of my biggest errors, and frankly pricing is something I always struggle with.

Over time I’ve found what works best for me is to partner with companies where this is their strength.

“for reference I work 60-80 hours a week and take about one day off a month”

“then if it makes a good story, save it for your grandchildren”

What grandchildren?

This “work ethic on steroids” which (I guess) has always been the norm in asia and is increasingly becoming normal in the rest of the world, especially in the tech sector makes no sense to me at all. Sure, it gets you money but what is money? It’s something you use to obtain what you really want or need. Once the basic necessities are taken care it completely loses it’s meaning if you have no time to enjoy it.

Or, put another way… I was lucky enough to be born into what used to be a very large extended family. I had and knew many of my family members from my great-grandparents’ generation all the way down to my own. I got to see a good portion of how they lived and unfortunately this also means that I got to see many of them grow old and die.

I had family members that worked very much like described here. 60-80 hours with rarely a weekend off. Mostly their spouses spent all the money, at least until they got lonely and found someone else. They had greatly reduced influence in their childrens’ lives and when they died.. well there just wasn’t much left to show they had ever lived.

Then other family members barely worked at all. Those people are a pan in the ass, a burden to the rest of us. But.. not for as long. They always sort of appeared about a decade older than others of the same age and mostly died much younger. At least in this country how much money you have really does determine the quality of your health care!

Work-life balance. Yes, it IS important!

“Once the basic necessities are taken care it completely loses it’s meaning if you have no time to enjoy it.”: Well said!!

Not everyone has the same scale on their work-life balance. I err toward spending time with my family. Work is a means to support them and I’ll never regret spending more time with them than I do my co-workers. Even though my co-workers are sort of like a family, they can never be like my own family. In the end, the one who dies with the most toys, still dies.

Donate to the kids.* ;-)

*Lots use to skip and save, and did all the above as ways of lifting themselves, and their children into a better life. So it only loses meaning if it’s just you, get some dependents and the equation changes.

Your point about kids had occurred to me. Also, financial security in the case of trouble. As the child of Depression-era parents, I saw that a lot of their saving was motivated by fear of the future.

But I’d sort of lump future security into the “basic necessities” category.

But if one works too much, there will not be enough time to produce some kids….

Only takes a minute or two!! :)

@ Eiko You have to spend time with said kids end up or you fail as a parent and said kids end up spoiled brats who only care about material things,delinquents who are always in trouble or worse.

Sure, but in the developed world it shouldn’t require 60-80 hour work weeks unless your family is unreasonably large, your only skills are far heavier in supply than demand or you are just doing it wrong.

Most people I knew who had family that worked those kind of hours their kids were always getting in some kind of trouble since they were never there.

They also always had some sort of nagging health problem and really did look much older then people who only put in 40 a week.

Karoshi is a real thing.

i’m mostly agree that if your job is your hobby as well then you are golden, but you also need to be compensated accordingly, otherwise they are stealing from you and you are fine by it :)

This is the part some people don’t realize about my 60-80 hour week: I spend maybe 20 hours doing “work” (invoicing, marketing, taxes), and 40-60 hours doing things I truly enjoy that other people happen to pay me well for.

In the end I have about as much time for family and friends as a busy person with an active hobby and a full time job.

No kids yet though — if that time comes I’ll restructure priorities of course.

Maybe I’m doing it wrong. I’ve found that all turning my hobby into a career did was suck all the joy out of it.

So… i’m assuming you have many millions by now?

I’m from canada too, 35hrs / week at average salary gets you above poverty, and that’s around 25k(can$) a year NET (after income tax). You can pay a house, a car, utilities, assurances, internet and other city tax with that salary. Get a roomate / GF and it’s halved.

1 million VND is worth around CAD 56 :)

Iksdjfei, in which Canadian villag…, err, “city” do you live???

This lets you potentially operate as a freelancer or part-time employee (depending on labor laws) in a sector related to what you want to do while you get the hang of things.

I think this is a fundamental mistake. You are either 100% invested in your Idea or you’re not. The fact you are willing/tempted to work on the side suggests that deep down you don’t believe in the viability of your core business.

I was tempted to do the same; I’m glad I didn’t. It hasn’t been an easy path, but at least it has been a focused one.

” This lets you potentially operate as a freelancer or part-time employee (depending on labor laws) in a sector related to what you want to do while you get the hang of things. ”

I think this is a fundamental mistake. You are either 100% invested in your Idea or you’re not. The fact you are willing/tempted to work on the side suggests that deep down you don’t believe in the viability of your core business.

I was tempted to do the same; I’m glad I didn’t. It hasn’t been an easy path, but at least it has been a focused one.

(edited for lack of tags)

This is excellent advice!

If you’re company is about a big idea, then you absolutely need to stay focused. That being said, if what you’re trying to do is operate as a freelancer, a limited liability company is a very useful thing to have. There’s also something to be said for learning to walk before running.

I didn’t study business so did need some time to pick up the fundamentals of accounting, invoicing, tax, how to manage people, marketing, sales, and all that important stuff typically learned in business school. At the beginning, I simply wasn’t experienced enough to execute Big Ideas both in terms of business acumen and local knowledge. To be honest, I’m still getting there, but I’m much more confident than when I started.

Late to the dance here again, and I have never set up outside of the US, but a few things…

1) You need to stay alive and that means eating and in most parts of the US, sleeping indoors with heat. So you may have no choice but to compromise the big idea to maintain yourself. It is not always a question of saying I need to stay on track unless the track is at least pointing slightly uphill.

2) You need to practise and get good at asking for what you are worth when you sell yourself. There is a huge spread. I have been known to suggest to people that they find someone else if they are just looking for the lowest cost per hour. On the flip side, I usually tell people I go far out of my way to provide the best ROI.

3) I almost never say no outright to anything. I will ponder things that are outside of my normal scope. I am always honest in that they will be paying for part of the learning curve though. Generally people who have worked with me in the past are pretty cool with this as they know how I work, and my ethic.

4) One of the hard ones for any engineer type, have a good handle on when you are done. Sounds simple but I have seen kids out there fight to get things much tighter than they need to be. Know when to call it good enough.

5) If you are starting a business be prepared for the long days and long nights and potentially years for things to get on solid ground. And be ready for a life where you will always be running around. You may be your own boss but the world around you spins and changes. The one constant is you will need a constant influx.

6) Even if you are feeling great doing the long days every day and the rare night off, be aware that you are burning yourself out and at some point in time you are going to have your fill of it, and it will no longer be enjoyable. I offer different advice than the normal do what you love. I offer do what you can do well and sell. It is better if it is not your passion, as it truly sucks when your passion is no longer your joy.

Good article Sean, thank you for sharing.

I think what most of you in the engineering fields don’t understand about Sean’s initial plight is that salaries for those with biology degrees are quite low at the bachelor’s and master’s degree level and often at the PhD level, as well. I guess like most things it all comes down to supply and demand.