“The prototype was $12 in parts, so I’ll sell it for $15.” That is your recipe for disaster, and why so many Kickstarter projects fail. The Bill of Materials (BOM) is just a subset of the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), and if you aren’t selling your product for more than your COGS, you will lose money and go out of business.

We’ve all been there; we throw together a project using parts we have laying around, and in our writeup we list the major components and their price. We ignore all the little bits of wire and screws and hot glue and time, and we aren’t shipping it, so there’s no packaging to consider. Someone asks how much it cost, and you throw out a ballpark number. They say “hey, that’s pretty reasonable” and now you’re imagining making it in volume and selling it for slightly higher than your BOM. Stop right there. Here’s how pricing really works, and how to avoid sinking time into an untenable business.

The BOM

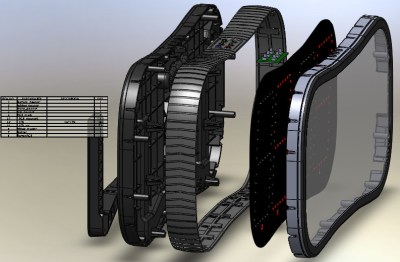

The BOM is a list of ALL components that go into a product. Sometimes you’ll have a hierarchical BOM, especially for an electronics project. Here you have a subassembly that includes the PCB and all its components, and then a product subassembly that includes the assembled PCB, enclosure, and fasteners, and then on top of that a packaging subassembly that includes the box and filler and manual and other stuff that’s not exactly the product itself.

Since it is quite possible that you’ll have multiple manufacturers and suppliers for different subassemblies, it makes sense to split the BOM into these separate categories, or at least have a column in the spreadsheet that makes it easy to filter.

The BOM needs to include every component; every bit of wire, every screw, every piece of plastic and resistor, including the amount of glue dispensed. Only then will you have a hope of understanding the complexity and cost of putting it all together.

The Labor

For a prototype or proof of concept, it’s a labor of love, solving problems that haven’t been solved before and creating a one-off. Going to production is an entirely different equation. Labor costs often exceed BOM costs, and cycle time for a process translates directly into money in some laborer’s pocket. Even if it’s you, your time isn’t free, and every second you spend doing assembly could be spent designing new products or enjoying life. There is a cost associated with the circuit board assembly, the complete build, test, and packaging. There is also a cost associated with setting up the assembly line for each batch. Every component in your BOM must be attached to the rest of the BOM somehow, making your simple assembly process an extensive production. This is why we design plastics to have snaps instead of screws, locating features that speed up assembly and reduce errors, and parts that perform multiple tasks rather than multiple parts.

Understanding the labor cost is essential to understanding the total COGS. One way to do it is to list EVERY step in the process, from taking a part out of a box to handing it to the next station. Every step then gets a cycle time. This is how long it takes to repeat that process. Add all the cycle times for your entire process, and you have the total amount of time it takes to get a product ready. Divide by the labor rate, and you have the labor cost per unit, not including the overhead of the labor.

An example assembly process. With a total of 10 minutes of labor per unit, you have an idea of your labor costs. Even if different people are performing the tasks, you’re still paying for that time.

| Operation | Cycle Time (s) |

|---|---|

| PCBA (SMT) | 420 |

| PCBA (Depanelization) | 10 |

| PCBA (THT LED) | 10 |

| PCBA (THT Battery Holder) | 15 |

| ICT test | 45 |

| Remove enclosure from plastic | 5 |

| Insert PCB into enclosure | 15 |

| Screw PCB in | 30 |

| Close Enclosure | 10 |

| Functional test | 15 |

| Prepare Box | 10 |

| Insert device into tray | 5 |

| Add Manual to tray | 2 |

| Slide tray in box | 3 |

| Close box | 5 |

| Total: | 600 (10 min) |

The Hidden Costs

When you buy a component, you have to pay for shipping from the distributor to your manufacturer. Then you have to pay for the shipping from the manufacturer to you, and you have to pay for the bulk packaging as well. You may have to pay duties or tariffs. Each of these things contributes to COGS. In addition, you will have waste and excess; a fraction of your production will fail and get scrapped, eating into your overall margins, and at the end of production you will have extra components due to minimum order sizes (you have to order 1,000 yards of fabric but only need 950, so the cost of those 50 extra yards gets distributed among the 950. You also have to store your materials and inventory until it sells, and that real estate isn’t free.

Depreciation

In most cases the tools used to make the product have a limited lifetime. Injection molds can have a lifespan from 5,000 shots up to 1 million shots depending on how much you want to pay, and after that you need a new mold. Other tools will eventually wear down as well or need parts replaced. These are additional costs associated with the COGS, and when you count your injection mold for plastic parts, die for packaging, cliche for pad printing, and in-circuit test fixture, functional test fixture, and other assembly jigs, that cost gets pretty high.

Note that the labor of designing the product or other NRE (Non-Recurring Engineering) doesn’t count into the COGS, but in order for your product to be viable you should have a good handle on this number and amortize it over the total number of units you expect to sell. Even if you make a good profit with fantastic margins, if you don’t sell enough units to pay for all the development of the product, you still have a net loss. The easiest way to figure this out is to take the development costs and divide it into the number of units sold and add it to the COGS. If it’s higher than your sale price, you are losing money. The difference here, though, is that you can make it up in volume. The more units you sell, the more distributed that NRE cost gets, until you are eventually profitable.

Putting it all together

When you add up all these costs, your product might look a lot more expensive than you first thought, but you have a much more realistic picture of the viability of your business, and whether you can sell your product at the price you want, or if you are forced to either cut costs or raise prices. Remember, this is just the COGS; it doesn’t include sales and marketing expenses, loss from theft or returns, customer support, other employee overhead, interest on loans, or profit margin. It all adds up quick, and it’s a wonder anyone can sell anything at a profit.

So, resale price = B.O.M. x 5 ? :)

More like BOM x 10. Possibly more,depending on the complexity of the product.

For a first indication when asking yourself the question: “Is this a viable product?” you can well base the decision on whether to proceed on a simple “Will this product sell for 10x BOM cost”. That’ll give you a ballpark to start market research. It’s NOT a good starting point for production. (Nor is any other guestimate. Calculate ahead of time!)

Nope, set resale to COGS X 3 and you MIGHT make a profit, and the you might not.

You’re totally missing the point. COGS = BOM + other stuff, and the other stuff is practically unrelated to what’s on the BOM, so there’s no “rule of thumb” that can be accurate.

I find it hard to believe the stuff on aliexpress etc follow this formula, it seems like electronics on there are barely above component prices.

You are correct in observing this irregularity. It seems they are selling stuff from China at stupid-cheap prices. I requently tell my kids that most of the time when people appear to be acting stupid it is because there is some other factor involved that we (the observer) don’t see and know about. When it comes to cheap Chinese electronics we are dealing with heavy government subsidization and just general logistical over-achievement that comes from disregard for the environment and a willingness to break any rule if it gets the product sold and shipped. The prices we see are not the real cost. The communist Chinese government is paying for part of it while destroying its own people’s environment (…toxic chemicals in the rice patties…unbreathable urban air and all that) and piling up a gigantic national debt. …not sustainable. My heart goes out to the Chinese people. Their government if driving them down into an economic hell-hole while other countries are becoming better exporters. Their communist way of doing things does not respond well to the needs of customers or citizens and they are always behind the curve at making good decisions if the decisions are good at all and not just political. Eventually they will fully consume the Chinese work ethic and even quality labor will become scarce. It is not going to be pretty for them. What else is new with communist/socialist countries? When will peoople learn that Carl Marx was an idiot?

Stop saying the word communist. It has nothing to do with it. The reason those parts are so cheap are because of these reason.

1. Off-reels from PCBA shops

2. Counterfeit silicon

3. Reclaimed parts from meltdown PCBs

4. Parts coming out the back doors of factories

5. Defect parts that are resold from non-certified vendors

6. Companies like Allwinner not paying royalties to ARM

“Stop saying the word communist.”

Lets make a deal here. You choose your words. I’ll choose mine.

Stop acting like a communist by telling other people what they may or may not say.

It *IS* about Chinese communist aggression. Communist governments are naturally aggressive, especially as resources run out because of their internal inefficiency. China is deliberately trying to take over specific industries for strategic purposes that are not entirely benign. A vast majority of Chinese people are wonderful souls but many in the leadership would be just as glad to shoot you as take your money for dirt cheap low-quality parts. We are nasty bourgeois pigs, you know. Everyone in a communist country is equal, but we know some are more equal than others and its that elite group that fears neither God nor man who has evil intent.

You are forgetting the near free labor costs. We can buy parts and sub assemblies very inexpensively from China. So their advantages as far as parts prices don’t really count. The thing we can not replicate on a mass scale is the near free labor. People in the US demand a lot more for their time.

The other place people screw up is expecting to have fixed costs. This will rarely be the case if your BOM is large. Some parts will fluctuate more than others, but you have to expect parts prices to change.

On the plus side, for the first few runs, you can count on labor time to go down, sometimes drastically as you learn better ways of assembling your marvel. Also, parts being scrapped through user mistakes and assembly errors should start to decline as you start to get better at assembling things.

China is hardly communist at this point, they have fallen for the free market story hook line and sinker resulting in the cutthroat competition and lack of concern for people and the environment. Screwing over your fellow man for profits is the MO of free market capitalism. Just look at the sickness taking over our own society. Whatever you feel like calling it, collective action and supporting each other is the only way we will be able to move forward as a society and reach the next stage in our humanity. Swallowing our pride and moving forward as a species is more important than arguing over who is using words right. In 100 years no one will remember this argument. I include myself in all of this as well.

There’s a long list of huge differences between the life sucking ways of communism and a free society.

(1) In statist societies including communism but also including any heavy handed tyrinical society, a soul must ask for permission or be told to do anything. If they do any thing “wierd” they are more likely to get smacked down by peers and authorities who are afraid of disrupting society. In free socities people are generally free to do what they want as long as it doesn’t harm others. It really comes down to who is regarded as the highest level of government, the individual soul or the bass-ackward concept that the central government is the top. We’ve had enough kings, emporers, fuhrers, warlords, sultans, ceasars, tzars,and beurocrats telling us what we may or may not do if you ask me. I think I remember a certain nation rebelling against all that nonsense 240+ years ago and the spirit rings on today in spite of those who would try to oppress. (The US declaration of independence is a good read no matter where you live.)

(2) As for environmental matters. Its the places where people have real liberty where the environment is best off. If you can actually keep your body and soul together along with keeping your posessions at your own home, you tend to take care of yourself and the things and people around you because you’ve got a long-term relationship with them. In settings where there is no such guarantee, its living in the moment, and to heck with the environment or the future. I’ve seen videos of places many Chinese people live in and they are pathetic, not because they aren’t hard working, but because the stuff around them isn’t really officially thiers and so why bother taking care of it? …like not replacing a lightbulb in a stair well or elevator because it’s not MY stairwell, and if the elevator breaks, its not MY elevator and there still is the stairs. Never mind bothering to change the oil in any gas engine to actually do maintenance. People there are crushed under a system that punishes taking care of stuff jet again building something up. That’s the authority’s job.

**HUG** communism!! Those who love it and want to force it on others can go hug themselves but leave the rest of us alone. Even socialism by itself without the antitheistic assault is seriously hugged up. 100 million dead and counting.

https://www.victimsofcommunism.org/

I could go on but I think that’s enough for now.

AND DON’T YOU DARE TAKE APART THAT ELECTRIC APPLIANCE AND TRY TO MAKE IT WORK BETTER. YOU DON’T HAVE PERMISSION TO DO SO!!! YOU DON’T EVEN HAVE PERMISSION TO ASK FOR THE FORM TO ASK!!!

Wow, somebody won a gold star at school in the ’50s.

Well it was US capitalists the exported US production to China.

Yea, we were really being short-sighted. :-) Having the best government money can buy didn’t help either. (The Chinese have been buying a lot lately) Sometimes we capitalists can be real suckers and at other times spectacular champions. It all goes with living the game of commerce and taking strategic/tactical risks. :-) Once the American citizens reel in power up to a more local level where it can be more appropriately controlled, things will likely get better. Talk about local power, wind/solar farming, personal manufacturing, and Bravo to that kid making his own semiconductors in his garage!! :-) There is still hope. …Recycling all that junk we keep making is going to be a real challenge though, but the solution will be done locally, not from some central authority dictating how we all should be doing it. We Americans HAVE been buying a lot of Chinese crappy products. Some day we will find ourselves mining our landfills that are full of them. ..that too might be a huge local opportunity some day. :-)

Have you ever been in China? The comments made here demonstrate how little you know about China, its people, its government and its society. Would anyone believe China’s rapid growth over the decades is short of sustainability? Why don’t you Youtube just a few videos how China builds its highways, bridges, railways and mega projects before you talk?

For real. Feel sorry for his/her kids.

I worked for one company that took parts + labor and them multiplied by 3x.

Overhead is a fixed cost, so it can be spread over the number of parts produced (some crimp tools can cost $300, so if you make 100 cables its $3 per cable, but only $.30 if making 1000).

Material handling is a cost. In-process inventory is a cost. Defects & scrap rates factor in (one-piece flow can reduce some of this significantly).

The common conception that a product is only worth little more than the cost of the raw materials that goes into it absolutely drives me nuts. In the past I’ve had to calmly explain to several resellers who wanted me to cut costs by an order of magnitude that my product just doesn’t assemble itself, it doesn’t write its own firmware, and program itself. This is all made worse when not made in mass as I’m doing a lot of manual labor by hand and my time is sure as hell valuable to me. I’m not going to just put in a bunch of time and effort and basically make a fraction of minimum wage return.

I get you but a product is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it. That willingness may be based on wrong thinking but that wrong thinking is just rationalization. Even without that rationalization they probably aren’t willing to pay more than what they have established. This has much more to do with other opportunities competing for their dollars and relative values, if you aren’t satisfying an actual need.

“I get you but a product is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it. ”

Hence the mixed message of the “P”-word. Desirable, but not to buy.

Sure but if what people are willing to pay, is less than it costs SJM there, then he’s not going to bother. If it’s some small hobbyist thing, an accessory for a long-dead computer or something, then he’s presumably making a small amount, as demand comes in, and doesn’t have a lot invested in it. So people can pay whatever SJM asks, or do without. In a market where there’s no competition, like lots of niche interests, that’s the choice people have.

Perhaps the resellers overestimated how much profit SJM was making. If he’s doing it for love, then he might not be charging much above his costs. Which is fine as a service to one’s geek community, but bollocks to breaking your back for some reseller.

“Why would I buy an expensive Xeon processor when a bucket of transistors is so cheap? It should be the same price!”

19.2 billion transistors x $0.01/piece = $192,000,000.00 That’s why ;)

…plus the cost of the bucket.

…and the labor of filling the bucket [while counting the transistors]

I think at this magnitude you just weigh the transistors.

Weighing parts to count them is a thing.

Amazon and the big box stores have really messed with people’s perception of what something should cost. I used to hear people all the time complaining that they could buy a similar product for much less at walmart, not realizing or caring that the small local joint pays its employees a living wage, provides them with insurance, and has to cover their rent and shipping expenses along with a million other little expenses. Its one of my least favorite aspects of working for yourself, explaining to people that I deserve to eat/pay my bills, and for that to happen I do in fact have to make a little money.

Well the good response is: “then go buy it at amazon/wallmart/whatever”.

If they do, it just mean for you that it’s time to find a new niche market.

Of course they may choose to forgo buying it at all in favor of buying something else more entertaining or needful.

or one that is just advertised better as well.

My friend has a business and many people say that, and he tells them they should go get/order it from that other place, but he has the part, he can install it now, so how’s it gonna be. Sometimes people realize it’s not worth to wait for that cheaper part.

Also don’t say BOM at an airport, say Bill of Materials. True story.

Don’t open your BOM spreadsheet in the airplane either, especially not with KiCad open next to it. I did that on my way to the #supercon. Rename it Bill Of Materials, preferably before you board.

(This was on KLM, a dutch airliner, and “bomb” in Dutch is “bom”.)

So how long did it take for you to walk straight? ;)

Pfft, we have a government BOM in Australia: https://www.bom.gov.au/

Many things just aren’t affordable or worth the price if they were made by local workers at a “living wage”.

Cheap mass-manufacturing in nearly 100% automated production lines have changed our relationship to production and consumption. As much as I’d like to support local industries, if I were to actually buy locally made good from a corner-store workshop, and all the other stuff, I could scarcely afford to wear shoes.

I mean, I can buy $20 shoes made in China. You can’t get -anyone- locally to make you shoes for $20. They wouldn’t even start thinking about it, because that’s barely enough to pay for the materials. Put down $200 and that’s closer to reality for a pair of shoes made by your friendly local cobbler.

Now extrapolate that everything you have now costs x10 because it’s made locally, by people who all demand a “living wage” which they understand to mean enough to afford all the same amenities you want to have – how much stuff could you actually afford to have? How much could they?

Playing devil’s advocate for a sec: the money you spend locally doesn’t get sucked into a blackhole and disappear, it will go to someone local who will then have more money to spend (hopefully) locally as well. If everyone just buys imported cheap stuff then it really is like the money disappears as if you are exporting the money anyway.

/devil’s advocate: I know economics are in no way that simple but complex problems require complex thinking

True, but the reason why the things you buy are so cheap is because they’re not made by people, or they’re made by people who are paid very very little.

To translate the same to the local scenario, there should be either a fully automated factory or a sweatshop in the neighborhood cranking out all the goods, and all the people would still complain about not getting paid a “living wage” while working some services sector job like flipping burgers.

If you want to pay everyone a “living wage”, i.e. the same living standards as you demand, you have to consider that you should be able to make everything your own by your own effort. Only in that case could you afford to pay someone else to do these things for you while enjoying the same living standards. That can only work if you have access and use of extensive automation and large piles of energy.

Most people don’t. Hence why we’re mostly relying on wage-slavery in the far east.

>”someone local who will then have more money to spend (hopefully) locally as well.”

More precisely, even if the money goes to someone locally, things still cost more in terms of price and so YOU in turn have to demand higher wages to pay for all the stuff you want.

Guess what happens to the other people when you are drawing higher wages to afford all the stuff? Of course, their cost of living will increase, and they in turn will demand higher prices yet again. Nothing changes, because the system is based on relative disparity: the reason why you are able to have a closet full of clothes, six computers, two cars in the driveway and all the other nice things is because there are people somewhere far away who create all this while getting paid a small fraction of its value.

If you had to trade value for value 1:1 in a locally closed system, you could barely afford to have half of what you currently own.

This sounds remarkably like the Industrial Revolution. Local workers used to make wool or cotton when not actively farming.

Putting that into a modern perspective: Soldering together some cute gadget, then selling it at a stall, could harvest you a few dollars profit without the added expenses of large scale production. Is there a point where “staying small” becomes more profitable?

That’s a fine idea, but it has to extrapolate beyond “cute gadgets” to make sense. Making and selling trivial luxury items does not bring you wealth – it only consumes resources.

That’s why the “post-industrial” services economy is slowly failing too: it’s based on facilitating the consumption of resources in order to shift some of the existing wealth from the rich to the poor – without creating new wealth to replace it. Some 4-5% of the population work to produce all the resources and another 4-5% refine them into goods, another 4-5% run the services that enable the production and the other 85% of people put up a huge consumption-oriented cock-and-pony show to convince each other that they deserve the money to buy the goods.

The obvious problem being that this money is no longer rooted to the productive ability of the society, but becomes solely about how much money is made up and given to people. The money collects up in different gambles and bubbles which become to define the social hierarchy ladder. A grand example of the culmination of this economy of triviality is Bitcoin, which is entirely based on wasting electricity and electronic hardware to measure who has the biggest E-penis: purchasing power is granted to the most wasteful.

Walking a mile in other’s shoes helps with that problem.

There are quite a few things left out of this: Depreciation rate (which is often dictated by tax policy), facilities costs, taxes etc. etc. One of the sad omissions in the “maker” world, as in the art world, is rigorous, boring training in accounting and finance, leaving a lot of the participants foundering as they try to make their way.

COGS isn’t close to the sales price, either. EEvblog #887:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwrkfHadeQQ

And, BTW, even this is still ‘cost plus’, which is a bad approach for capturing the value of something.

Wait, is he selling turbo encabulators? I been looking for one since 1987

and, I was just about to post this. HTere is also a TheAmpHour episode about this. John Saunders of Saunders machine Works (YouTube: NYC|CNC ) also has pretty good information.

Also forget to include cost risks such as: “lost in the mail, resend/refund”; “customer x wants refund because y”; “bad shipment of parts”; and the grandaddy of them all “being sued by x because of y!”

There are a f-ton of risks involved in selling something/running a business and insurance only covers some of them…

I currently am in the process of setting up some of the infrastructure for answering these questions at the company where I work. My biggest stumbling block is that we make a product that requires design work from several unrelated CAD packages. I’m looking for a generic BOM format that would be a good future-proof input for CIM (computer inventory management). Is there an accepted format for generic BOMs (or at least a set of accepted formats)?

“Is there an accepted format for generic BOMs”

do you mean file format or information formatting?

For file format: CSV is generally the easiest way to do it and allows for the largest compatibility between software packages.

For information formatting: there is no standard, its all data manipulation anyways and if you are putting it into a CIM then all you need to do is make sure the right values get mapped to the right database values on your input.

I can think of dozens of viable ways to do it. CSV was the first thing that came to mind, but I’m looking more closely than saying “CSV” while waving my arms. Why I am looking for are standard implementations so that I can get all of my engineers to set up their various CAD and other documentation packages so that they all spit out BOMs in a single format. Rather than reinvent the wheel and roll my own (which we will then be responsible for maintaining), I’d like an accepted standard that achieves what I need that I can implement.

Arena Solutions has several white papers, blog posts and other resources talking about BOMs

https://www.arenasolutions.com/resources/articles/excel-bill-of-materials/

I mean, depending on what level you’re talking about, the “big boys” that I’ve worked at tend to use Oracle’s Agile PLM database for tracking this sort of thing. Basically, there’s a list of components we use (resistors etc), and they each get an entry in the database. When you upload a PCBA BOM from your favorite software (orcad for example), it links against the database part numbers. Often you will have an internal part number MyCo-1234 that has multiple normal part numbers attached to it, for instance AcmeResistor1K, and NewCoResistor1K. That way you can have multiple sources for each item.

The commodities guys can then pull a report, and get the price on the spot.

Some projects to study:

EEV blog’s micro current, which is not much more than a fancy opamp an some precision resistors in a box, but sells for USD80 or so.

Mechaduino, which is an open source product, with all the info on the ‘net and it is a quite small board, but sold commmercially for around USD50.

Actually any open source project which is also sold commercially is open to some easy basic analysis between BOM cost and selling price.

I was curious about the “calculator” box. Custom machined by NY_CNC (Also featured on Hackaday). That product has long dissapeared from his web site.

It also seems very unrealistic to time things like “put device into tray” and “close box” with any kind of accuracy. Much better to assemble a small batch, and calculate assembly costs from that. Probably also correct for startup troubles etc.

But startups often have to make estimates of such costs before some realistic measurement can be made, and do not have the experience to make those estimates accurate.

There are also lots of other things to consider, such as feature creep and product placement.

One of the stepper motor drivers I looked at has an Oled display for setting / displaying some parameters.

Looks nice in a video, but I’d rather have a solid communications protocol with a PC and some high resolution graphs to plot control loop results to fine tune PID parameters. Compatibility with the LinuxCNC scope would be much more interesting than an OLED display for me for example.

Low volume businesses, such as those selling on Tindie, don’t generally have the resources to do a realistic COGS calculation. What can be done fairly easily is to calculate the fully loaded parts cost (i.e. including shipping, taxes etc.), the direct selling cost (e.g. selling fees, packing and shipping) and an estimated per unit labor cost (based on their time at an hourly rate they find acceptable). Then selling at 2x that cost might allow a hobby business to make some money. A real business would have to sell at much more than that to be worthwhile. The 10x BOM cost is probably about right for that. I never cease to be amazed at how low the mark up is on many goods sold on Tindie.

I remember a guy who sold a wood humidity meter for $100, when his BOM costs were about $10. He sold them based on the value provided and the cost of alternatives, not based on an X factor over his COGS. He sold a lot of them.

This is exactly how it should be done. Figure out how much it costs and figure out how much you can sell it for. Make a go/no-go decision from there.

Yeah, the market can be weird. Some 25 years ago, I was working on the core of a editing system which was superior and vastly cheaper than the competition. As a result, customers viewed it with suspicion. Crank the price up, and they then took it seriously, and it sold well…

In the old days when HP was starting they just multiplied the cost of BOM by Pi. Been a bunch of engineers that seemed a good approach I guess.

Right. Because engineers just multiply things by Pi. Oh wait, I guess that’s about what Scotty did with time estimates.

“Note that the labor of designing the product or other NRE (Non-Recurring Engineering) doesn’t count into the COGS”

NRE stands for non-recurring expenses, not engineering and or can very well be represented in your cogs, depending on how you choose to account for amortisation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-recurring_engineering

The problem with putting it in your COGS is that it can confuse the unit cost. If you amortize the cost of your NRE (whether it’s engineering or expenses) into N units, then on the N+1th unit your COGS drops significantly without any real change in production. If you amortize it over the expected number of units in forever, you are likely wrong so the number means less. Either way, you’re not going to get a perfect answer, but either way you still have to have an understanding of the NRE and how it contributes to the cost of what you’re making.

When you’re busy developing prototypes, maybe you should take time to read 《Principles of Economics》.

Which one? The earlier one by Carl Menger in 1871 (my favorite) or the later one by Alfred Marshall in 1890?

you know what else nails people,,,,TAXES. Ive seen several projects run into a brick wall when the founders forgot to factor in uncle sams cut and set their pricing below COGS+Taxes

The silver lining here is uncle sam (and most other countries) allow one to deduct the cost of doing business on taxes, meaning you do not pay tax on equipment, your parts (you can get a resellers license to avoid paying sales tax, I have one), your rent, wages you pay your employees, you’re vehicle, insurance, ect. Now ongoing taxes like payroll and registration cannot be deducted.

Source: I used to own a computer refurbishing business in college and had a couple of Employees.

I was surprised to find out how expensive retail packaging was. Even on ebay, Has anyone found blister packs for 20 cents or so? I wish I could buy some that were made for another product, but would fit mine.

I refuse to believe that the blister pack from my harbor freight multimeter costs a dollar….It’s a 6 dollar meter!

Could you make your own blister packs with a vacuum former? I’ve never tried but I’ve seen a few Youtube videos from people who have. The parts look fairly cheap, a heater and a vacuum, and then you can just buy the plastic and make a custom pattern. Look up the channels “I Like to Make Stuff” and “Punished Props Academy”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ynFpxokWlM

I’ve considered that but cutting the edges of the cardboard inset and edges of the plastic is not something I want to perfect. I’m convinced there is someone that orders thousands of these and can sell a few from their stock…Just have to find them. Or become them!

I’m trying to estimate costs for a kickstarter project I’m going to reveal soon. Great article!

You are speaking my language! As the Engineering Manager for an EMS provider that also owns several tasks in the quoting process, I deal with all these terms on a daily basis. Whenever we deal with start-ups, much of this has to get explained because soany don’t understand it.

Anyhow, very nice article, well done and clearly explained for the HaD audience.

Soany=so many

Since I didn’t saw it here, don’t forget your solder :) It might sound silly, but when you go through paste for your boards quickly, it gets noticeable, too.

One can sell below COGS if it’s a loss leader. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_leader

I was designing networking equipment around the turn of the century (prior to the dot com bubble collapse). We had products with interfaces running at 1Gb/s to 10Gb/s (N.B. not 10G Ethernet – that was still a year or two in the future). Some customers needed 10 and 100Mb/s Ethernet, so we had to include a product that did that. It cost almost as much to make as the higher speed versions, but customers expected to buy it for 1/10 the amount of a 1G unit (’cause it had 1/10 the throughput), so that’s the price we gave it, the idea being that those sales would enable sales of the higher speed units (which had a large markup).

N.B. actual cost may not have been 1/10 the cost of a 1G unit. Memory fails me. It’s also complicated by the customers were interested in “port port” costs, and the lower speed units had a lot more ports in the same space compared to the higher speed ones.

s/port port/per port/

Even better if you create an off-shoot company and organize it as a charity and manipulate your loss-leader’s volume to kill competition.

ala Broadcom and Pi Zero

Just make sure you do it in the UK because there are laws against that in most 1st world countries.

Still, there weren’t many boards of that power available, at anything like the price, even of the first 25 quid Pis, at the time. The Pi, and Arduino, created a market for dirt cheap dev boards, once the Chinese saw a success they could copy. We’ve probably benefitted more from the Pi driving prices down, than we would have by letting competition between ARM SoC vendors do it.

They had something like a lazy cartel, where nobody bothered bringing prices down because nobody was really asking for cheaper ones. Opening up the hobbyist and the “stick a Pi in it” market created much more demand, unforeseen when the boards were more expensive.

About the example: PCBA (SMT) is 420 minutes? That sounds outrageous to me, unless performing the work by tweezers and candlelight. SMT is suitable for pick and place.

Never mind, that’s 420 SECONDS, not 420 MINUTES :-)

Don’t forget to add the cost of calculating the COGS…

from my experience, a quick rule of thumb if something cost you 10$ (landed) to make, you sell it 20$ to toysrus and they sell it 40$ to the consumer. (1,2,4) (obviously this depends of many, many factors)

And this is the reason why the New World was discovered, the desire to bypass the middle-man and buy spices directly from the far East rather than paying a bunch of turbine wearing price gougers. Some things are pretty well a constant. …middlemen, bureaucracy, disease, taxes, getting older, stuff falling apart. At least the world is mostly predictable. :-) …Actually the Indians we were trying to reach often wore turbines too. Must be a rather practical clothing choice given the environment at least when it isn’t the rainy season and/or not being outside. Might be helpful, even inside, if one’s wife has a tendency to throw pots. :-)