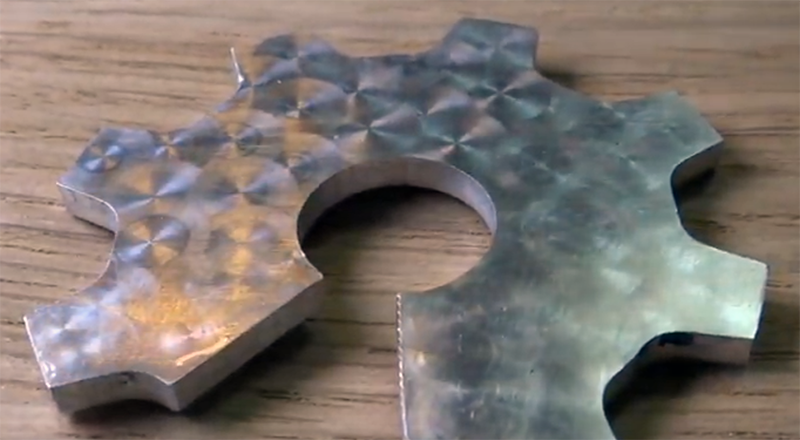

Engine turning, or jeweling, or guilloché, or a whole host of other names, is the art of polishing a pattern of circles on a piece of metal. You see it on fine watches, and you’ll see it on art-deco metal enclosures. [Ariel] decided to explore this technique and ended up getting good results with a pencil eraser and toothpaste.

The process begins with a piece of aluminum, in this case an aluminum Open Source Hardware logo. The only other required components are a number 2 pencil, some toothpaste, and any sort of rotary tool, in this case a drill press. Toothpaste is spread over the piece to be turned, and a pencil is put in the chuck. It’s just a matter of putting circles on the aluminum after that.

This is, incidentally, exactly how engine turning and jeweling are done in the real world. Yes, the tools are a bit more expensive, but you’re still looking at a somewhat soft tool scraping a fine abrasive into a piece of metal. The trick to engine turning comes in getting a consistent pattern on the piece, something that could easily be done with a CNC machine. If anyone out there feels like putting a pencil in the collet of a CNC router, we’d love to see the results.

If you don’t know about Ariel, check out their other projects, they’ve got a ton of really cool and innovative things over the years.

Thanks Arthur

I did this when I restored my table saw a few years ago, but I wrapped a piece of scotch-brite around an adjustable furniture foot and chucked that up in my drill press. It worked great!

This is how I did it as well: steel wool on the end of a rubber-tipped dowel in my CNC mill.

Have seen this done very well with a wine cork as well. You can trim to the size desired on the lathe. :)

Interesting, i should try that

Mdf makes a nice flat buffing surface that takes compounds or abrasives well. The price and wide availability are nice too

https://cdn.bluegrasstoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Lindy-and-Spiritof-St-Louis.jpg

Watched a documentary years ago about the Spirit of St Louis, this is a version of the patterning they did on the engine cowl. In that documentary they were doing it in a drill press with a wire cup brush.

He can also glue a piece of sandpaper on tip of eraser i think he will acheive better result, creative and nice work anyway

Yeah i wanted to try this just to me very basic. Im now using a Dremel SS brush that words awesom

I was here to comment the same. I haven’t done guilloché using a physical lathe, but there are some interesting Wikipedia articles about the mathematical backgroud of these patterns:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epicycloid

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypotrochoid

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roulette_(curve)

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rose_(mathematics)

Also, don’t forget the Spirograph and the Fourier series.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spirograph

There is commercial software to design computer-generated guilloché patterns for security purposes, like banknotes and certificates. Excentro and the defunct TorApp are valid examples.

Actually, the sand paper wears down and you don’t get a consistent swirl that way. Using a rubbing compound lets you recharge the tool, basically. Cup brushes are OK too, but I like the MDF or a dowel and some compound.

A plain wood dowel with some rubbing compound works well too.

This is jeweling/perlage, but definitely not guilloché, which requires a rose engine lathe (or a straight line machine) and a single point cutter.

(source: I have a rose engine lathe and do guilloché work with it.)

Can i see some of your work, looks interesting

Thank you, one of my pet peeves is people confusing perlage with guilloché. I’d kill for a rose engine. Metaphorically.

OP is correct. I don’t own a rose engine (aka guilloche lathe), but I have actually done real engine turning (guilloche) on an actual rose engine for an afternoon with the US expert David Lindow.

He runs a wonderful newsletter you can sign up for that covers the real deal at his website, https://lindowmachineworks.com.

Brittany Nicole Cox of Memoria Technica in Seattle does several classes a year with him teaching beginners real engine turning and it’s quite reasonably priced. If you’re interested in this topic there is actually a society for this in the US, the Society of Ornamental Turners: http://www.the-sot.com

Technically what this technique is called among horologists and ornamental turners is “spotting”, aka perlage.

It can be done many ways but it’s pretty much the same- either an abrasive pad or wire cup wheel in a drill press milling machine or even hand drill. There are specialized machines within the watchmaking community that are quite rare designed to do this on watch movements and watch cases, and they use typically a wooden dowel turned to the diameter of the peralage spot you want to make, charged most often with diamontine ( diamond powder) of varying mesh sizes, usually around the equivalent of 300 grit I believe, or finer. The machines that are specifically designed to do this rely on the fact that the machine spindle is not perfectly perpendicular to the work surface by only fractions of degree.

I learned this in watchmaking school.

It’s actually easy to do this, spotting (perlage), but extremely challenging to do actual engine turning (guilloche). That involves a very special type of cutter that is half burnisher, half neutral rake cutter.

Interesting, I’ll have to keep that in mind!

Past weekend I documented some jeweling I did on CNC lathe using a spindle and an extra stepper to rotate spindle.

https://youtu.be/bxCYP3Y5FNo

Another project with a knife and CNC router.

https://youtu.be/8gIOTxotZGg

Just last week, I was looking into CNC machine turning/jeweling and and ran across Cratex Jewelling Rods. They are like giant pencil erasers and seem to be fairly affordable.

Cratex stuff is pretty good but extremely abrasive. You might take off more metal than you intend. They’re also somewhat soft so you’d have to use a collet or some other support system so only a tiny bit is sticking out, and then advance it over time as it wears. But it does a great job for smoothing soft metal.

You can do something similar to “sunburst” your watch dial too…

https://www.watchrepairtalk.com/topic/9970-revisiting-an-old-hobby/?page=6&tab=comments#comment-98791

1/8′ arbor T-post from the air grinder, handful of rough scotch brite pads and an Allen-Bradley controlled knee mill ended as the winning solution in my one and only attempt at perling. It’s really not much harder than programming a series of drilled holes it turns out, IIRC I ended up using a canned cycle that was rapid in-rapid out with a dwell prior to out, feed cranked to the gills but only at maybe .02 depth to build a little pressure to get the pad cutting and just let it rip. End result was WAYYYYYYY better than it had any right to be.

I agree that CNC is the way to go. For my cylindrical parts I wrote some g-code macros and they came out great. With some flat pieces I used F360 and the only problem I had was the optimize path needs to be turned off. You want a regular pattern for best results. There is no way I would ever spend the time and repetitive motions on a drill press. I used the brownell’s spring brush jig which worked fine but shorter and smaller shank diameter would be nicer.