Before PCBs, wiring electronic circuits was a major challenge in electronics production. A skilled person could make beautiful wire connections between terminal strips and components with a soldering iron, but it was labor-intensive and expensive. One answer that was very popular was wire wrapping, and [Sawdust & Circuits] shows off an old-fashioned wire wrap gun in the video below.

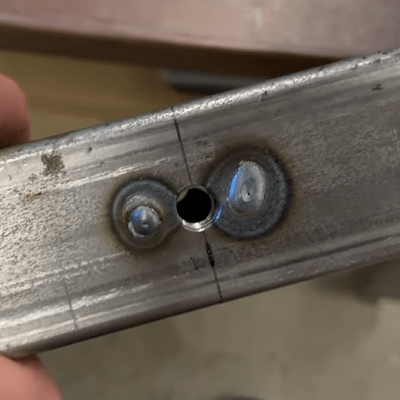

The idea was to use a spinning tool to tightly wrap solid wire on square pins. A proper wrap was a stable alternative to soldering. It required less skill, no heat, and was easy to unwrap (using a different tool) if you changed your mind. The tech started out as wiring telephone switchboards but quickly spread.

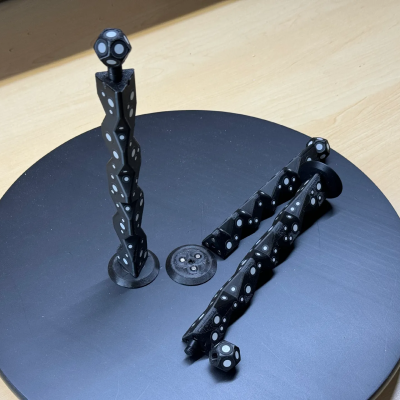

Not all tools were guns or electric. Some used a mechanical handle, and others were like pencils — you simply rotated them by hand. You could specify levels for sockets and terminals to get a certain pin length. A three-level pin could accept three wire wrap connections on a single pin, for example. There were also automated machines that could mass-produce wire-wrapped circuits.

The wire often had thin insulation, and tools usually had a slot made to strip the insulation on the tiny wires. Some guns created a “modified wrap” that left insulation at the top one or two wraps to relieve stress on the wire as it exited the post. If you can find the right tools, wires, and sockets, this is still a viable way to make circuits.

Want to know more about wire wrapping? Ask [Bil Herd].

![[nanofix] and his assortment of tweezers](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/nanofix-tweezers-banner.jpg?w=600&h=450)