Engineering degrees are as wide and varied as the potential careers on offer out in the real world. There’s plenty of maths to learn, and a cavalcade of tough topics, from thermodynamics to fluid mechanics. However, the real challenge is the capstone project. Generally taking place in the senior year of a four-year degree, it’s a chance for students to apply everything they’ve learned on a real-world engineering project.

Known for endless late nights and the gruelling effort required, it’s an challenge that is revered beforehand, and boasted about after the fact. During the project, everyone is usually far too busy to talk about it. My experience was very much along these lines, when I undertook the Submarine That Can Fly project back in 2012. The project taught me a lot about engineering, in a way that solving problems out of textbooks never could. What follows are some of the lessons I picked up along the way.

It’s A Team Game

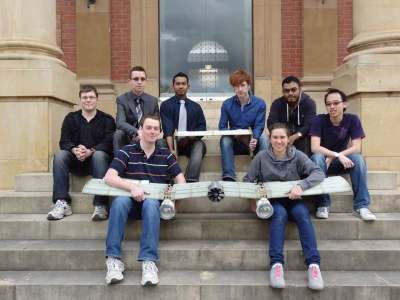

Engineering is a team sport, and a big capstone project will drill this into you quickly. The bigger the project, the larger the team, and it’s important to learn how to work in such an environment in order to succeed. I led a team of seven other budding engineers, who aimed to design, build and test a flying submersible vehicle in just under twelve months.

In that team, there were a mixture of personalities, skills and cultures. Keeping this in mind is key to getting the best out of your people. There’s little to be gained by demanding your orthodox Jewish team mate show up to work on Saturday morning, just as it makes little sense to put your fluid mechanics expert on to dreary stress analysis problems. A happy team is a productive team, and it generally makes sense to play to your strengths where possible. Understanding your team is key if your project is to be a pleasant experience, or a disaster.

We were lucky to have a broad spectrum of abilities across the team. One member stepped up to manage the team’s documentation, becoming a pro at LaTeX. Another put his modelling abilities to work on the CAD side of things, while another ran the stability calculations to ensure we’d have a working aircraft at the end of the day.

Obviously, it was important for all team members to have an idea of the greater scope of the project, but allowing team members to find their niche helped everyone buy in to the greater whole. Sometimes, difficult decisions had to be made, and there will always be work that nobody wants to do. But by sharing tasks carefully and with everyone contributing to the best of their abilities, we were able to achieve more as a team.

Get this right, and you’ll have a less stressful project, and finish with a group of lifelong friends. Get this wrong, and you’ll get destroyed in the peer assessment and never want to talk to your team again. You’ll be spending a whole year in the trenches together, so make sure you choose the right people!

You’re Gonna Have A Lot Of Meetings

Unfortunately, when you’re working with other people, you’re gonna have to have meetings to keep everyone abreast of developments. This goes for team members, as well as outside stakeholders such as sponsors or project supervisors. If managed poorly, these meetings can become excessively long and tiresome, so it’s important to stay on top of things.

Agendas should be short, sharp, and shiny – and provided in advance. It’s a massive waste of time if you’ve called a meeting and nobody has brought the necessary materials because you didn’t make it clear beforehand. It’s likely your project supervisor is a professor who is busy with all manner of other things, and won’t tolerate such mistakes, so don’t make them in the first place.

It’s also important to keep discussions on topic. Don’t spend 40 minutes discussing the relative merits of fiberglass versus carbon fiber when you haven’t even decided on a basic layout for your vehicle, as an example. These things happen quite naturally, but it’s important to pull the conversation back to the key agenda topics if you’re going to get out of the room before sundown.

Finally, it pays to learn when you’re communicating effectively. If you’re raising your voice or stating the same thing over and over again, and people still aren’t understanding you, it’s likely time to change tack. You may need to understand their position first, before beginning to explain your own. Also, drawing a diagram often helps. Or in my case, getting someone else to draw a diagram because your own skills are somewhat lacking – Thanks, Lara!

Making Stuff Is Hard

If you’re lucky, you’ll go to a university with a well-equipped machine shop. They’ll let you spend untold hours turning out parts, and you’ll graduate with a great appreciation of the machinist’s craft. We weren’t so lucky, and instead had to prepare drawings to have our parts produced by the university’s own machining staff. This in itself is a powerful learning experience, as it’s important to be able to create drawings to standard that can be properly interpreted by others.

Between the university’s workshop and our CNC machining sponsor, we learned from experienced operators what works and what doesn’t in a variety of machining methods. Sitting down in meetings with our production partners, we were able to learn from their decades of experience. We set about refining our parts to cut production costs to the bone, something we likely wouldn’t have thought to do had we been let loose ourselves on the tools. Learning from the pros about how to minimise set ups and avoid repetitive tool changes reduced our costs by a factor of ten.

There were also pitfalls along the way. Our composites knowledge was weak, and we were trying to do some things a little unconventionally. Combined with a miscommunication, our wings ended up twice as heavy as intended, significantly harming our flight performance. Capstone projects are strictly time-limited due to the constraints of the degree, and a small mistake such as this one proved difficult to remedy after the fact. It’s important to stay sharp and detail oriented, from start to finish.

Don’t Forget About Presentation

A significant part of a capstone project is documenting and presenting the project. The reality is, many capstone projects fail to achieve all of the lofty goals they set out to reach at the start of the year. Ours was no exception – our flying submarine did become airborne, but failed to achieve a submersible mission before deadline. Despite this, the true purpose of the capstone project is to learn – and our documentation and presentations reflected this.

We were able to discuss the stability criteria and structural requirements for a fixed-wing submersible vehicle. Our testing regime had highlighted the viability of using a single ducted thruster for both air and underwater propulsion. We’d also learned how to build effective thrust testing rigs, as well as unconventional wing structures with some success. In this regard, we had a lot to show for our work, and many other teams were in the same position.

By producing clear documentation of our work, and presenting our final seminar with clarity and focus, we were able to communicate to the audience and markers the value of our project. This in turn led to us achieving solid grades, which is what we were all there for in the first place!

In summary…

If you’re approaching your capstone project, a little prep work done early can go a long way. Find a project you’re passionate about, and assemble a team of students with the right attitude and skills to get the job done. Prepare yourself for the inevitable mistakes along the way, and soak up as much knowledge as you can from the people who are there to help you. Your capstone project can be a great stepping stone towards your eventual career, so it pays to get it right. Good luck with your studies, and if you’re doing something really great, you may just want to let us know!

Would that I could have chosen my project. Our Capstone projects were assigned, and unfortunately I was assigned to a project that frankly didn’t contain much to interest me, as it had nothing to do with my engineering concentration, (predominantly a mechanical/industrial project), and was sponsored by a company that decided to kill the project some time during our second semester without telling us.

I spent one of the longest amd most frustrating years of my life trying to be useful as an electrical engineer on a project that legitimately only needed an electrical engineer for just about a single day of work. My entire contribution from the electrical side was sizing an AC motor, the correct wire gauge, and the very rudimentary ladder logic needed to run it from a foot pedal and incorporating an end stop. It took me about 30 mins it, and about 3 times that to write up and diagram. To make matters worse, someone felt that these moderate tasks needed not one EEs, but rather two! I did what I could to help in other areas, but mostly I was relegated to documentation and administrative tasks. I wish I had fond memories of Capstone, but frankly I feel like it was a huge waste of time and money.

Oh man, that is terrible! I can’t imagine who thinks assigning capstone projects is a good idea. Sorry you had to go through that bud, I agree, waste of time and money.

One thing I’d note is that every university is different when it comes to these types of projects. We were teams of two or three, corporate sponsorship were not common, and projects focused on functionality, not fluff (presentations). IMO, you are going to school to be an engineer, not a marketing person, graphic designer, manager, or a sales person. Why is so much emphasis put on those things at some universities? If they want custom graphics, flashy presentations, and structured management, why doesn’t the university get the relevant schools involved in the project?! I mean, a lot of engineers dabble in other ‘arts’ like graphic design and project management, but that isn’t what you are paying the university for. Just seems silly.

I loved my project. I was already working so I didn’t spend as much time as I should have on it, but it worked!

The presentation portion of a capstone project isn’t about marketing, it’s about communicating what was accomplished and how the technology works. This is a critical part of the engineering process. It doesn’t have to be flashy and marketing like, but it does need to be clear and concise; achieving both is an invaluable skill to a competent engineer. I can’t tell you how many engineers I’ve worked that didn’t have this skill and how hard it’s been to communicate with them. Ultimately just about all had their careers severely limited by this deficiency.

Just about everything in this article relates directly to work where I am juggling about 6 -10 projects at a time. While I haven’t done a capstone project, I would certainly consider a technical capstone project on a resume as prep for life in IT.

Fort Hays State University has a capstone class for IT (information networking and telecom) bachelor of science students. I don’t know what it entails (I didn’t do the BS program, only the MS), and I can’t find a concise description of the class, but it seems appropriate for perspective future administrators and analysts.

Different universities and countries have slightly different systems obviously.

Here in the UK they’re just called a final year project – and they aren’t necessarily team based. I did a solo project for mine. Anyway – I think there’s a couple of things you can add to this list that are worth bearing in mind (I think!). Obviously these are based around having some choice over your final year project.

1: Choose something that interests you :

Its a lot of work and you’ll be driving yourself – that’s much, much harder if you’re not interested. You’ll naturally put more work in and do better if you care about the project. A good project, that you’re interested in doesn’t just serve you well at uni, but in your first job interviews you’ll have something to talk about. Something you can talk about animatedly, will take you a long way.

2 : Make sure there’s different types of skills involved :

Couple of reasons for this. It allows you to demonstrate an understanding of how different “tools” interact and apply more of what you’ve learned. It also reduces your exposure to failure. So rather than a project that solely focuses on say, FEA or a build and test of something, choose one that involves some simpler FEA and a build and test. If one element of your project is unsuccessful then you’ll still have plenty to talk about.

3 : Don’t over-reach :

It’s easy to get sucked in at the beginning into dreaming up a project that you’ll struggle to deliver. Understand what you need to reach a minimum viable result. It’s better to do something more modest and do it really well than try and try to deliver the moon on a stick – and end up with a stick. The best thing would be something that you can scale up or down depending on . There’s a lot going on in you’re final year – be kind to yourself.

4. There’s a good story in failure as well as success :

“The best laid schemes of mice and men go oft astray” or “shit happens”. If stuff doesn’t work out how you’d planned – fail well. Test results give you a different answer than you were expecting – concentrate on showing how your original assumptions have been challenged by reality.

Thanks for the bit about being cool with Orthodox Jews and Sabbath.

I am one and I have had my troubles with university group partners and employers.

We can be the best(or worst we are human) part for the job but I greatly appreciate working with people who can treat my day off and what I can/can’t eat etc as a fact on a datasheet rather than passive aggression or openly begging I break my rules.

I do not exclusively exist for a team or an employer and a day away form your topic a week and some other rules are part of getting me or others of my tribe who don’t roll on shabbos to work with you, these rules probably also contribute to better mental health as we do take time away from work to have family or at least away time.