With electric vehicles such as the Tesla or the Leaf being all the rage and joined by fresh competitors seemingly every week, it seems the world is going crazy for the electric motor over their internal combustion engines. There’s another sector to electric traction that rarely hits the headlines though, that of converting existing IC cars to EVs by retrofitting a motor. The engineering involved can be considerable and differs for every car, so we’re interested to see an offering for the classic Mini from the British company Swindon Powertrain that may be the first of many affordable pre-engineered conversion kits for popular models.

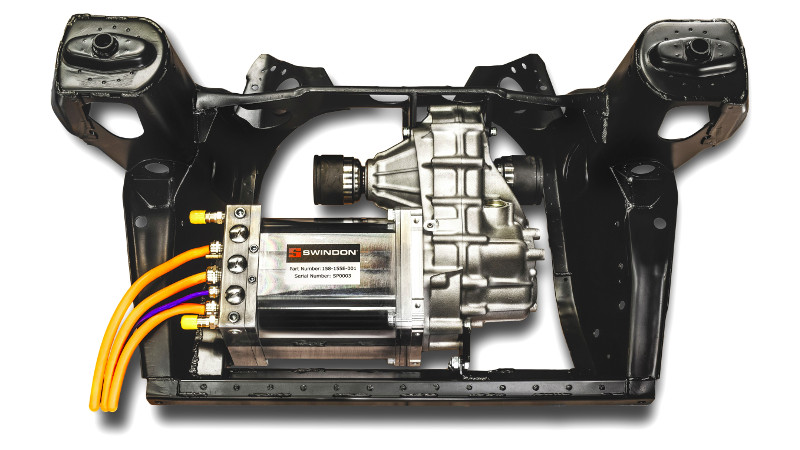

The kit takes their HPD crate EV motor that we covered earlier in the year, and mates it with a Mini front subframe. Brackets and CV joints engineered for the kit to drop straight into the Mini. The differential appears to be offset to the right rather than the central position of the original so we’re curious about the claim of using the Mini’s own driveshafts, but that’s hardly an issue that should tax anyone prepared to take on such a task. They can also supply all the rest of the parts for a turnkey conversion, making for what will probably be one of the most fun-to-drive EVs possible.

The classic Mini is now a sought-after machine long past its days of being dirt-cheap old-wreck motoring for the masses, so the price of the kit should be viewed in the light of a good example now costing more than some new cars. We expect this kit to have most appeal in the professional and semi-professional market rather than the budget end of home conversions, but it’s still noteworthy because it is a likely sign of what is to come. We look forward to pre-engineered subframes becoming a staple of EV conversions at all levels. The same has happened with other popular engine upgrades, and no doubt some conversions featuring them will make their way to the pages of Hackaday.

We like the idea of conversions forming part of the path to EV adoption, as we’ve remarked before.

This isn’t the only one.

electricclassiccars.co.uk in Wales are starting to do kits for the original VW Beetle and Land Rover Discovery.

25kWh Beetle kit for about £20k.

thats the trouble the cost for conversion is huge – its still in the realm of well funded enthusiast.

I was doing up a Beetle with my daughter a few years ago and it needed an engine – $1000AUD for a petrol ebgine vs $20000AUD for a EV conversion.

Ive got a Kombi Im working on at the moment which im still open to the idea of EV’ing it but the cost is still prohibitive.

20k to convert a beetle? Great idea but really? A lot of people are struggling to keep their head above water as it is!

I don’t think anyone struggling will be the target market for this, I’m not struggling at the moment and I would not even consider it.

I think the truth is that a conversion will never be an economic option in the short term. Running a classic car is not an economy. Even running an older car becomes uneconomic sooner or later.

To some it’s blasphemy of course, removing a Ferrari engine from a Ferrari 308 may make it quicker and more reliable. But no one can say it’s the same car. However I’m sure that there are many Ferrari owners who would trade an unreliable engine for a conversion, so that they can use it every day and stem the flow of money to mechanics. Whether there’s ever a payback will depend on the case, but if you want to have a practical and classic every day car this is an option.

Some people have savings. Not like you pay check to pay check.

Most people aren’t going to blow 20,000$ on an ev conversation kit.

im no mini fan but I was under the impression that the dif in the mini was of set as per the conversion – or maybe it varies per model

its cool to see these drop in kits – but I dare say they will come at a cost …

Does one need a safety certificate, approval, what not to be able to drive a converted car on the road? What is considered minor vs major mod if that defines approval requirements?

The answer is, I don’t know. However the UK IVA test is not a huge expense, and a pretty straightforward thing to put a car through.

The mini gearbox sits under the engine, and I’m pretty sure its diff is at the centre at the back. A while since I drove a Mini, any Mini fans care to comment?

Having done an unholy amount of work on my Minis in my misspent youth, yes the diff is offset. The knock on effect of this is it caused my very highly tuned one to change lanes when accelerating hard if uncorrected. This electric kit really appeals to me…. hmmmm….

(ps hello to any lurking Mini-listers)

“The knock on effect of this is it caused my very highly tuned one to change lanes when accelerating hard if uncorrected.”

Aaah, the joys of torque steer.

OK, my memory is faulty then.

>hello to any lurking Mini-listers

Hello to you. From a Mini Fan and lurker :-)

It’s of interest to anyone who is concerned about the (considerable) amount of C02e that the manufacture of a new vehicle generates. So thank you for the pointer.

I’ve just contacted them for a quote for a 30 year old Peugeot 205, as I’d much rather convert than buy new,

I guess though that public transport and service vehicles ought to be first in line for conversion.

First of all, that a new EV costs a “considerable” amount of CO2e is a myth. A new electric car has “paid back” itself in CO2e emissions after about 8-12 months, but then keeps being cleaner for years. Remember, even an electric car run on oil fired electricity is about 50% cleaner (in CO2e) than a petrol/diesel engine, due to the efficiency of an electric power plant + transport, and terrific efficiency of the battery+electric powertrain (often above 90% efficiency).

For public transport vehicles: In the Netherlands most buses run 8-10 years after which they are only written off economically, but also techno-economically (maintnance and repairs become more expensive than buying new), and this is mayor parts of the bus, not just the engine. The company I work at (Connexxion) has bought new electric buses over the last few years – the concession I now work at (Noord-Holland Noord) has 83 electric buses, 38 diesels, and 2 natural gas, and about 62% of kilometres is run electric, that’s about 6.5 million electric kilometres annually. Another concession, due to start july next year, will be 100% electric.

It really is not a myth – just the refinement of the steel is a huge energy cost all new vehicles have (and in 99% of cases its an even higher carbon cost than just the energy as making steel is a carbon intensive process – though electric foundry options are starting to be trialed and look promising)

And you really can’t claim paid themselves back in any particular timeframe without knowing where the electricity comes from – if you generate it all yourself via solar/wind for example it can pay back the carbon cost rather fast. But powered by the rather horribly dirty Chinese coal power stations (for example, there is alot of variation in grid ‘greenness’ globally) it might never pay back the costs…

https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-how-electric-vehicles-help-to-tackle-climate-change has an informative graph, showing a new Nissan leaf will pay back the emissions compared to keeping driving your old car in less than 4 years (in the UK). The 8-12 months I quoted earlier is when a new ZE is compared to a new IC car.

I work in the electric bus industry, and we estimate that electric buses run far longer (15 years) than comparable diesel buses (8-10 years), and we see that batteries hold up far better (degrade less) than what manufacturers presented us, so after only 3.5 years of running electric buses (for the first 47, we now have over 250), we are already thinking about a 1-battery-change strategy instead of a 2-change over their 15yr lifespan.

Luckily I do know the resource mix of electricity used in the Netherlands. It’s 41% natural gas, 39% oil, 12% coal, 6% renewables and some change. With a relatively low renewable percentage, the natural gas really makes this a lot cleaner than many neighbouring countries that don’t rely heavily on nuclear (such as France). Source: https://www.ebn.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/EBN_Infographic2019_14JAN19.pdf

Indeed, Electric really has a space in an efficient future. Its just not as cut and dried as x months in your are making a net gain. Too many variables with the big one being the grid you are charging offs credentials.

So for me in the UK, folks in France with their big Nuclear and to some extent Germany (as the 3 have some beefy interconnects to spread the greener energy around leading to record import and export figures for them all and are all getting cleaner) as an example can be fairly sure an EV will in its lifetime pay back its not that universal, you have to do enough miles and places with hideously dirty grids still exist. For now at least… (For me it would be even more certain as we have a solar installation on the roof, though I expect it would be a better carbon and money saving element having all that extra battery to power the house as I almost never go anywhere using 4 wheels…)

For my total milage its way way greener to keep any old box going.. as in a year I might have done a few trips to the hardware store etc. But prefer pedal and walking for the occasions I have to go somewhere.

“The 8-12 months I quoted earlier is when a new ZE is compared to a new IC car.”

Yes, but what about comparing a new ZE with keeping your existing IC car?

Don’t forget the energy cost of the battery manufacture. The rule of thumb is 10% of the theoretical lifetime capacity for how many cycles it lasts, so for a 25 kWh pack that’s about 5,000 kWh extra energy on top of what usually goes into building a car.

Apples to apples, the CO2 emissions of a “globally average” EV matches that of a 51.5 mpg regular car. In the US grid mix it’s about 55.4 mpg, and natural gas power plant would do 58 mpg gasoline equivalent.

In the link IIVQ provides above you can see that the battery is included with the calculations in that study.

As long as it is this expensive, I’ll be burning fossil fuels for the foreseeable future.

Why ruin a perfectly good classic car with a kit that gives you a range of 80-120km when you can buy a new electric car with much better range and keep your classic car in stock condition.

Some say “But the range is totally OK, you don’t drive a classic that far anyway”, the bigger reason to not convert it then, a car that you drive a few times a year doesn’t pollute that much anyway.

Some say “But if it was electric, I would drive it as a daily” No, as a car guy, it’s fun in the beginning, but “all the comforts of a car from the 60’s” is none…

Classic cars are best as nostalgic memorys, once you drive them again you realize how bad they really were

Also, they are deathtraps if you crash them (both stock and as EV’s) , for people who concider that important

That said, I drive a lot of old cars, with leaky ventilation windows in the doors that whistle in highway speed, without AC, with mediocre to bad brakes, and I like it

Driving electric is much more enjoyable regarding peaceful driving, but more fun is 100% torque from 0 mph, and pure analog acceleration, no let-up for shifts. Feels like driving a go-kart, especially if you’re using regen, one pedal drivjng.

I bought a 1963 Triumph Spitfire to restore. After getting frustrated with the amount of rehab and parts availability cost I decided to convert it to electric. I did a good amount of research and was able to pick up parts reasonably. It’s a great conversion and now have it running. Very pleased with the results. Off to the paint shop in a few weeks.

Send us a pic when done, well done

An original Mini provides a special driving experience, the rubber suspension means it corners on rails, and its size means you are more connected to the wheels than almost any other car. If you are a mini enthusiast than it’s completely worth it, I can see.

I agree why that could classic I’d rather drive a gas island if they delete and got gas stations I would rather switch to buy a Isaac fuel which is basically deep fryer from the restaurant before switching to a EV as a native

This really isn’t “affordable” for the average person at all. By the time all the essential add-ons are included the price goes way out of the range of the person on a national average salary, which are the exact group that EVs should be targeting. Totally impractical rich man’s plaything – nothing more.

It’s affordable in the sense that a new high-end BMW is affordable. It’s more than I earn, but in the unlikely case I wanted one I could buy one with a loan.

It’s true, it’s not affordable as in “costs pennies”. But there are options at that level, see some of the things the Irish subsidiary of https://www.newelectric.nl/ are doing.

Indeed, this is £10k for just a motor and a frame, it doesn’t include the motor controller, the charger, the DC-DC converter, the coolant pump, the limited slip diff, the speed sensor OR the batteries. You’re heading fast towards £30k and haven’t even installed it yet. Companies like this are going to get destroyed once the Chinese companies turn their attention to the rest of the world.

Given that a Bolt EV motor + transmission is around $3500 – I’m surprised we haven’t seen more people do conversions based on this as opposed to a custom unit at 3x the price.

Also, 150 kW power handling capability vs. 80.

For comparison whole conversion to 140KW Honda B16, including labor cost will cost less than this motor/frame conversion kit alone. http://superfastminis.com/store

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UN7tl7nhV0s&list=PLp0KnUFYB–g4RJ0SomuWRqckXHCYkabS

Pity the whole kit costs more than a brand new electric Mini though.

Yes, that is true cost is everything. i’m looking for a Baja conversion kit. Seen anything like that?

Too bad this one:

https://electrek.co/2019/11/26/jaguar-halts-electric-e-type-zero/

is halted. Hope to see it ome day though, and I wouldn’t mind a drop-in for my XK either.

Too rich for my blood…

Interesting..

“The Italian Job” film from 2003 used a group of Mini vehicles, all powered with electric internals.

The theory was, driving gas power in the different tunnels and such was a hazard.

Like most “Movie Magic”. I’m sure the gold bars used were fake also.

GM is releasing the Chevy Volt drive train as a “Crate Engine” for car customizers.

It’s a wonderful time, minus the pandemic.

provided the “conversion crate” is offered for reasonable money, it really would be a wonderful time. Minus the pandemic of course.

It isn’t it is 10000£ for motor, transmission, and the subframe. The are charging several thousand for putting this into the subframe. This motor and gearbox can be bought elsewhere. They sell everything else separately.

The total cost including batteries, inverter and charger, etc is £37k. Ridiculous money and no great A series noises anymore.

The details, (Minus Price) are here: https://arstechnica.com/cars/2020/10/chevrolet-readies-an-electric-crate-motor-for-homebuilt-ev-hotrods/

Not sure how much the total kit price will be, but for reference, a brand new 150 kW motor+transmission is around $3500 from gmpartsdirect

Also, it’s a Bolt not Volt powertrain

WHAT! Those gold bars were not real?

I can’t believe it. How could they do that?

I am really waiting for the first to fit an electric car with a turbine + generator so you can drive electric and just tank diesel or any low grade fuel. Small buffer battery so you don’t have to switch the turbine on 100% of time

Chevy Volt

After testing, Chrysler conducted a user program from October 1963 to January 1966 that involved 203 individual drivers in 133 different cities across the United States cumulatively driving more than one million miles (1.6 million km). The program helped the company determine a variety of problems with the cars, notably with their complicated starting procedure, relatively unimpressive acceleration, and sub-par fuel economy and noise level.

1) those were powered directly by the turbine, Erik was writing about either a turbine/electric hybrid or an electric car with a turbine range extender

2) those were the friggin’ 60s dude. We can be build better turbines now. Much better.

We can, but not easily. Chrysler later tried to improve the fuel economy by adding a heat recycling system, but it proved to be too expensive to manufacture.

Same thing with modern microturbines – the turbine itself is simple, but the efficiency of a once-through turbine is still limited by thermodynamics and you have to add elaborate heat exchangers to it, or compound it with a lower temperature steam turbine.

If you are not running with much electric store you are almost certainly better off just running a normal ICE – the efficiencies of modern combustion engines are not bad, and conversion efficiencies from kinetic to electric to kinetic make the whole onboard generator, to drive motor little better if any. There are some specific cases where such systems can make sense, but its rarely for efficiency as its not a big gain if any.

Yes, batteries. But the idea of the generator is to facilitate long trips. Accepting that 40+ miles trips are only occasional for most users, the benefit of electric efficiency still makes it well worth it. With the volt, I’d use $20/ mo electric and $20/ mo in fuel for all of the commuting and extra tooling around, maybe 1k miles or more.

Aye, if you actually have some real battery pack – it takes a real pack to give an electric car any range at all… Can’t really describe such things as ‘buffer battery”. And lugging extra weight of the hybrid part if you do lots of long haul just makes the system efficiencies worse than a good ICE. The reason you take the plug in hybrids is because they offer you enough range to do most of your trips fully electric, while still able to go visit Aunt Mable 400miles away in the one vehicle – if you never need to go further than an Electric can go, or are usually traveling further you are probably better off with a proper EV or normal ICE – not the blend that takes on the mass of an EV, but without the electric range and the corresponding hit to fuel efficiencies burning carbon..

Yes, battery is not the solution for long haul driving. That’s why Daimler is still pushing on fuel cell technology for otr trucking. I think the question is whether it’s practical to convert ICE to EV or Hybrid, and clearly one size does not fit all. What I am saying is that motor companies thought long and hard about how many miles the *average* commuter drives to determine the best battery size. 40 miles round trip is definitely at my threshold for a commute, and anything up to 100 miles will cover the extra errands and only add 200 lbs curb weight. Most drivers are not putting on a ton of miles, but at the same time want the comfort of knowing they can. Tesla is the only EV maker bent on long range batteries, the rest are making commuter cars for people that have a second vehicle to cover the long hauls. I can’t talk enough about how practical the Volt setup is, and I’m extremely happy to see it didn’t just become the 3 peat for GM’s alternative vehicles, if you know what I mean.

Also, I’m surprised myself to find there’s actually no difference in weight between pure EVs and hybrids, either way it’s 200 lbs. I’d love to kit out a Suburban like that for an adventure rig, or even the minivan. I bet that K5 conversion they got is a blast to drive!

A direct drive turbine is likely to want more volatile and fluid or even gaseous fuels, particularly at smaller scale to fit in cars.. So burning petrol and alcohols not low grade viscous fuel oils and diesel… And making a steam turbine so you can easily burn anything means carting lots of water around and filling up often or really good condenser units neither will really fit in a car, even the massive things Americans call cars..

Take a look at the Lincvolt that Neal Young ran for several years. It had a custom controller that would fire up the turbine as needed. He eventually replaced the turbine with a diesel generator.

Volvo did that in the 90’s with the ECC, they had a prototype even earlier too, but I can’t remember the name of that one.

A modern turbine is a simple one button touch start, no procedure at all, everything is programmed into microcontrollers that uses sensors and automates the process.

The ICE starting procedure used to be “Pull the decomression level, prime the carburator, pull the choke, advance the ignition and install the starter crank, and start cranking”

Noone thinks that is how it is done today, why would turbine engines be complicated to start today?

This kit is a bust. It is really not that big of a deal to mate a motor to an adapter plate and bolt it to the original transmission. The main use case I could see for this is a garage doing electric original mini conversions along with restoration. The conversation done and labor saved, the cost is passed along to the customer.

Yeah you can make your own plates if you have the tools (which if you are maintaining a classic you should have the bare minimum tools to do the job) but how long will it take you? The kit means you get 2 months of weekends maybe more back and just bolt it all together, worth the price for many folks – even more so if its really well engineered and machined for ‘effortless’ fit (I’m assuming that you will loose most of a few weekends with the ‘hmm I need this or that part/tool afterall’ and waiting for delivery cycle – the plate shouldn’t take that long to make).

Not the case witth he Mini.

The gearbox is under the engine, and shares the engine oil. The clutch sits on the end of the unit, with a co-axial shaft arrangement, and a gear train to the box. It made sense in 1959, but it’s not just a case of bolting the motor to the end of the gearbox as in end-on gearbox cars.

Swindon Powertrain’s transmission is interesting because it is a much smaller unit more like a transaxle. I look forward to seeing it appearing in kit cars designed specifically for it, which could have unconventional form factors due to not having to find space for an engine and positioning the batteries for best weight distribution.

You will get a kick out of the Rosen Motors hybrid car from the 1990s which used a compact turbine and a flywheel.

https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1996/09/30/217438/index.htm

Yes, one cluster after another.

I spent twenty years building turbine power plants, and I believe they are not suited for vehicles.

Airplanes, perhaps very large trucks, ships of course, but cars, NO.

There was also the UAC Turbo Train by Via Rail and Amtrak. Dead and gone since 1984. Turbines are light, but not very fuel efficient compared to a reciprocating engine. If you can find one, get an old aircraft APU, or look this up on U-tube… Deutz T-216 … much lighter than a 100 HP Diesel engine… challenge is 40L per hour.

APU power systems are suited for the military, where fuel rates are not important.

Dr. Marious Paul built many small APUs based upon a small turbo, and adding a hot end.

He’s gone now, but he was a joy to meet and talk with. Very smart guy.

I foresee megafactories sprouting in all the continents where you can drop off your DGC (Dirty Gasoline Car that some call ICE) car in the morning for “service” and after work you pick up your old bran new EV.

I foresee just these conversion kits being so impossibly expenssive (without the work a batteries and stuff), that only the rich can afford it. And IF they would ever get to be cheap enough, original EVs are already the mainsteam by that time and the conversion kits are not going to sell enough and the price will not go down because of that.

Would it really be better to make a bunch of megafactories all over the world to keep cars going with marginally better emissions instead of just getting rid of ’em and going with proper mass transit? All these green schemes just make me think that the eco movement (not climate change science itself, mind you) is a total and complete scam. People just want to make a buck off it and are totally cynical about actually solving any of the problems, often just making them worse in their eternal, heliotropic pursuit of the bottom line.

Probably – Getting people to give up freedoms they have is never easy, made worse by the fact public transport in many places seems to be either an overpriced joke or unable to actually take you more than vaguely close to where you want to go (sometimes both, and sometimes it doesn’t exist at all).

If you put in the billions upon billions to build an efficient effective mass transit system, you are going to have to charge enough to use it that people won’t – its cheaper to run their own (heck round here its been demonstrated that its cheaper to buy, insure, fuel and run a second hand car than take the train for the same journey – and in the real world the car is probably better still as it takes you door to door and can be used for other trips as well)..

Its often not clear even if you do charge a lower amount so you get users how big an improvement it will be either – as the upfront energy and carbon costs of infrastructure like that are enormous – so it has to last with low maintance for a relatively long time, and get a great deal of users – running a train for bugger all passengers is the very opposite of ‘green’. It definitely can be the best option, by huge margins in some places – but running a decent mass transit system all through rural Wales/Scotland or the vast areas of the US and Canada with no big cities for example probably isn’t better for the planet, and definitely isn’t cost effective at all – Where making it possible to and then getting rid of cars in cities probably will be.

So while I won’t say you are wrong about a degree of cynicism and profiteering in the way companies are using the peer pressure and public awareness of climate change and the whole green movement that has finally got moving (decades later than it should have been), its still not entirely a bad thing – being a step towards or less wasteful society that might just keep our little blue dot habitable.

To make transit of people environmentally friendly is simple – just don’t travel as far or as often – in the age of the phone and internet you don’t need to travel as often to keep up with friends or family. Don’t get me started on the stupidly low airfares that has large percentages of the developed world going on holidays all over the world every single year… Or the stupidity and red tape around things like electric skateboards and bicycles – by far the most efficient way to travel with powered help. But ultimately just don’t travel as much and you are not ‘wasting’ so many resources.

Do they sell the electric motor with a drop in air bag and side impact protection kit option as well?

Honestly, I feel safe in my little Mini. Out of the factory, it had 37 horsepower, which isn’t enough to get yourself into trouble with. And the fact that they make everyone’s head turn, no one misses seeing that little car.

I’ve had to actively swerve once in the past couple of years due to an absent minded driver. In my normal car, that’s a weekly occurance.

The only bad thing is the weak brakes, but you get used to giving yourself a little extra room between your car and the next.

I won’t lie though… driving a right-hand drive in America, you feel like you’re gonna die for the first couple of days on the road!

there is no way in hell a classic mini has the space to fit airbags that will actually do anything beneficial in a crash. Ditto with side impact, you need space for that. If the door is pretty much touching you and is barely 1/2 the thickness of a modern car door, forget side impact protection, not happening.

no crumple zones either :) :)

Throwing it out to the Hackaday community, I’ve got a first gen 1962 Mini, right-hand drive that I brought over from Northern Ireland.

I’ve talked with Swindon, but I wasn’t able to gain much info (it seems to be a bit less straight-forward of a conversion than the press release and the articles suggest), but if anyone wants to join in / learn from / help with a little math on my conversion, I’d love the camaraderie.

One big change I’m going to do (it’ll make the purists roll over in their graves) is I plan to replace the center, circular speedometer with a circular touchscreen monitor. Most other changes will be focused on the EV system.

https://hackaday.io/rybot

Ryan

Oh — Im in the Pasadena, CA area!

It would surely be much easier to buy a leaf or Zoe complete and build it into the mini. I own a 300hp 1.4l rover k series engined mini and have helped many others swap modern engines into their minis. It’s always much easier with a complete donor car.

I’m really surprised at Swindon’s updated web shop. The HPD-2 – the first Mini swap they offered – was about $3000 less ($3000 is a TON for a drop-in frame!), and buying the inverter on the link below, you save some $650. Buying it as a part of the new kit costs an extra $650??

https://webshop.swindonpowertrain.com/index.php?route=product/product&path=95&product_id=261

I’d love to learn more about your Mini swaps!

http://www.16vminiclub.com :)

We don’t really need an EV conversion kit for classic cars, we need cheap EV drop in kits for 10 year old cars people can get cheap.

You’d be surprised how cheap you can pick up a Mini for, there were 5 million of them made, after all!

Where? The average price I looked up was north of $13,000. Not astronomical, but not exactly budget for an outdated junker to use in an EV conversion.

I found mine on a tiny site of classified ads that I had never heard of before. $13,000 is a reasonable price for a Mini these days, but you’ll be able to find one in good shape for under $10k if you search and give it a little time. :)

Amazing how “green” stubbornly continues to be a luxury market. Really gives away the plot imo.

The original classic mini had an offset diff with different drive shaft lengths on each side so the kit appears to be correct in that regard.

OK. I remember mine wrong. It’s 30 years ago. :)

And you can pick up a new Mini body shell in UK. Add this, and you have half a old style classic electric Mini. In France there is a company that converts old french cars to EV, turn key solution.

Still the greatest classic mini conversion ever – and totally hacky yet glorious:

http://spagweb.com/v8mini/gallery/scrap/index.htm

Front-wheel-drive V8 3.5 litre mini using mostly Austin/BL parts-bin parts.

The original Mini’s differential is offset to the right (as viewed from the front), just like this. The output from the transmission is on that end, *and* the bulk of the engine is shifted that way as well.

It sounds as if you haven’t taken one apart and assembled it several times.

On the new MINI’s (BMW, MK1, 2003-ish) the driveshafts are equal length – but they get that done with a short shaft between the diff and the inner CV joint on one side.