Being able to vocalize is one of the most essential elements of the human experience, with infants expected to start babbling their first words before they’re one year old, and much of their further life revolving around interacting with others using vocalizations involving varying degrees of vocabulary and fluency. This makes the impairment or loss of this ability difficult to devastating, as is the case with locked-in syndrome (LIS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and similar conditions, where talking and vocalizing has or will become impossible.

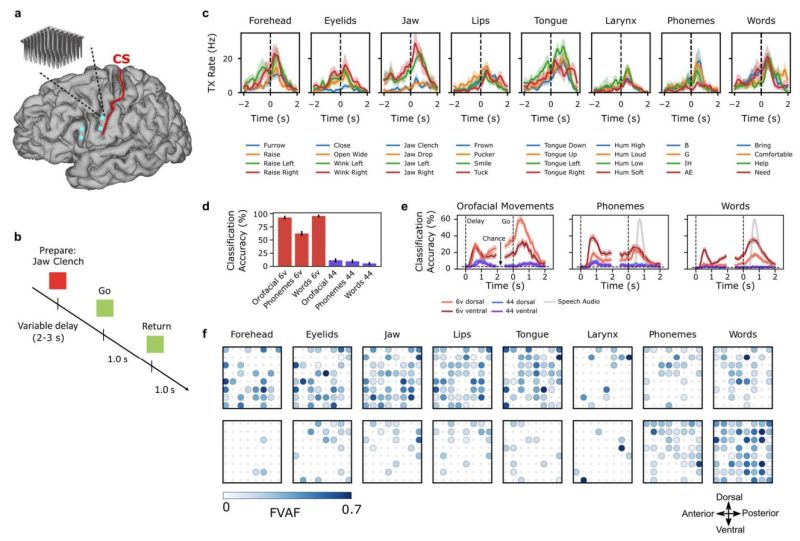

In a number of concurrent studies, the use of a brain-computer interface (BCI) is investigated to help patients suffering from LIS (Sean L. Metzger et al., 2023) and ALS (Francis R. Willett et al., 2023) to regain their speaking voice. Using the surgically implanted microelectrode arrays (Utah arrays) electrical impulses pertaining to the patient’s muscles involved in speaking are recorded and mapped to phonemes, which are the elements that make up speech. Each of these phonemes requires a specific configuration of the muscles of the vocal tract (e.g. lips, tongue, jaw and larynx), which can be measured with a fair degree of accuracy.

In the case of the study by Sean L. Metzger et al. as recently published in Nature, the accompanying research article on the University of California San Francisco website details the story of their patient: Ann. At the age of 30, Ann suffered a brainstem stroke which rendered her essentially fully paralyzed. As an LIS patient she lacked for a long time even the ability to move her facial muscles.

Although some functionality has returned over the years, being unable to use her vocal tract to vocalize and speak coherently has left her largely unable to connect with her then young daughter, except via a basic synthesized voice. With the experimental system, Ann’s phonemes are decoded and passed through a voice synthesis network that’s been trained using Ann’s original voice, sampled from an old wedding video. Although the current BCI system is wired and clumsy, the hope is that a future wireless version could give her and many like her a portable version that would make every day life that much easier.

Heading image: Microelectrode (Utay) array location and the decoding of the corresponding actions. (Francis R. Willet et al., 2023)

I always think about failure modes with all technology. And putting metal inside someones brain, I see as high risk, high reward. But what happens in a car crash (TBI – Traumatic brain injury) or even just the jerk from a elevator stopping, when daily. I will admit to knowing nothing about LIS or ALS, and I’m sure that BCI has the potential to drastically improve patients quality of life. I do not question the benefits, I’m not poking BCI with a stick, but modes of failure have always interested me.

an interesting mode of failure is the company going belly up…

Hey editor, might want to fix this.

“As an LIS patient she lacked for a long time not even the ability “

This would be very useful for aphasia sufferers.

Let the subjects decide on their pros and cons.. Every deserves to be happy and alive not alive and miserable.