Throughout history, clean and potable water has been one of the most prized possessions, without which no human civilization could have ever sustained itself. Not only is water crucial for drinking and food preparation, but also for agriculture, cleaning and the production of countless materials, chemicals and much more. And this isn’t a modern problem: good water supplies and the most successful ancient cultures go hand in hand.

For instance, the retention and management of fresh water in reservoirs played a major role in the Khmer Empire, with many of its reservoirs (baray) surviving to today. Similarly, the Anuradhapure Kingdom in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) featured massive reservoirs like Kala Wewa that was constructed in 460 CE with a capacity of 123 million m3. In the New World, the Maya civilization similarly created reservoirs with intricate canals to capture rainwater before the dry season started, as due to the karst landscape wells were not possible.

Keeping this water fresh and free from contaminants and pollution was a major problem for especially the Maya, with a recent perspective by Lisa J. Lucera in PNAS Anthropology suggesting that they used an approach similar to modern day constructed wetlands to keep disease and illness at bay, while earlier discoveries also suggest the use of filtration including the use of zeolite.

Resource Management

In climates where rainfall is plentiful, and where wells can fill in gaps, extensive water management is not a major concern. This is where the civilizations of Mesoamerica provide good illustrations of the effects this can have on societies, with the Aztec and Inca using aqueducts to bring mountain spring water to their cities, while the Maya in their region with a karst topography had to capture every drop of rainwater before it would vanish within the hollowed-out structures that are a distinctive feature of these soluble carbonate rock landscapes.

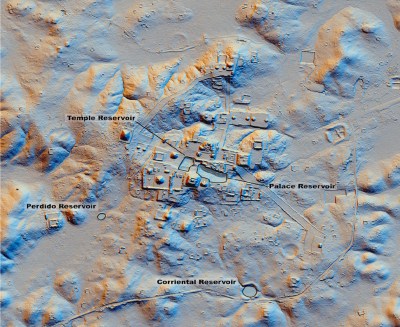

This meant that the only time when the Maya could refill their reservoirs was when it rained, which also placed significant restrictions on how much water would be available to any population. It is postulated that it was a drought and reservoir pollution led to the eventual abandonment of the Mayan city of Tikal (ti ak’al in Yucatac Maya, but Yax Mutal (‘First Mutal’) according to inscriptions within the city) after the Late Classic Period (~900 CE). This preceded the Terminal Classic period, during which much of the lowlands were abandoned.

There is strong paleoclimatological evidence for a sustained drought between 800 – 1000 CE (likely related to the Medieval Warm Period) in and around the Yucatán Peninsula, coinciding when archeological evidence shows a reduced human presence in these lowlands by the Maya. It’s thought that these droughts coincided with epidemic diseases in combination with dense populations and intensification of agriculture with associated ecological destruction. The post-classical Maya period featured far less dense cities, and despite the often used term of ‘Classic Maya Collapse’, Mayan society was only regionally affected and persists to this day, despite efforts by European invaders and associated occupation over the centuries.

Filtration

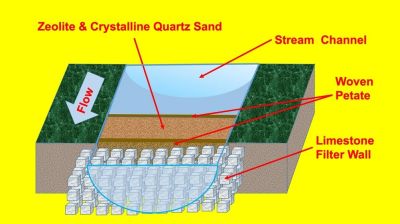

Water filtration is something that happens not just with man-made structures and mechanisms, as anyone who uses water from springs and wells knows. The granular structure of soil serves to filter out larger and smaller contaminants as well as bacteria and other potential disease carriers. This same principle can be applied with artificial water filtration systems, with the Corriental water reservoir at the city of Tikal providing evidence that the Mayans even used the zeolite mineral for its water purification properties.

This was discovered by Kenneth Barnett Tankersley and colleagues, and published in 2020 in the journal Scientific Reports. They discovered that the water in this reservoir was filtered through a mixture of zeolite and coarse crystalline quartz. Zeolite is interesting, as it has adsorbent and ion-exchange properties which make it a popular choice even today for water purification to the point where most zeolite is synthesized for this and other purposes.

As for whether this extensive filtration in Mayan reservoirs was common is unknown, as the authors succinctly point out that the number of excavations of these reservoirs is quite limited. The presence of zeolite would have significantly helped with filtering out contamination from microbial sources like cyanobacteria and toxins such as cinnabar (mercury(II) sulfide). The latter is both a historically common brilliant red pigment as well as a good source of toxic mercury due to its mercury sulfide composition. Unfortunately this kind of filter does not help against mercury from volcanic sources due to its very small particle size, meaning that this type of contamination would have built up over the years in reservoirs.

Circle Of Life

The term ‘constructed wetland‘ pretty much gives away the concept: these create an artificial wetland ecosystem where plant and often also animal life work to treat sewage, greywater, stormwater runoff, and wastewater in general. They provide both a filtration function and a remediation one, with the vegetation along with microbial life serving to break down and process excess elements, while maintaining a healthy pH and nutrient levels.

In the mostly stagnant water reservoirs which the Maya maintained, preventing the build-up of organisms and harmful pollutants was essential, leading to likely extensive use of aquatic plants in these reservoirs. This is reflected in the headdresses, architecture and other elements of Mayan culture where the clean water-loving water lily (nymphaea ampla) is prominently displayed and associated with prosperity and the leadership.

Likely many different aquatic plants were used in combination with water lilies, along with various types of fish. This would have helped to deal with pests like mosquitoes and their aquatic offspring, reduce evaporation and creating a self-sustaining cycle where the waste from the fish would have provided nutrients for the plants, who themselves would have provided shade and food for these fish. Settlement maps show that the Maya did not generally build residences near the reservoirs, likely keeping human waste run-off to a minimum.

This healthy system did however begin to break down during the Late and Terminal Classic period, with the sediment record showing a gradual increase in contamination from cyanobacteria and human waste. This gives a sobering insight into the final years of the city of Tikal and areas like it that got hit worst by the drought.

Lessons For Today

Although we often like to regard droughts and access to potable water as historical problems, even today one in four humans does not have access to safe drinking water, with unsafe water being responsible for about a million deaths each year. Unsafe water can include water that is contaminated with infectious diseases such as cholera, with much of Africa and Asian countries like India heavily affected in this manner, but even wealthy countries like the US seeing its share of drinking water contamination incidents, with that of Flint, Michigan, being just one of many.

Such forms of contamination and lack of access to safe drinking water are obviously issues that ought to be resolved and prevented as well as possible once the cause has been determined. These days we don’t necessarily have to rely on constructed wetlands courtesy of modern technology, but they could be very beneficial as a self-sustaining water purification system.

As the US Geological Survey (USGS) points out, we are dealing with increasing drought since 2000 as well. This doesn’t merely translate into less rain, but also changes in the rain and melting patterns, as well as the availability of groundwater. This becomes apparent in periods of extreme drought interrupted by extreme rain accompanied with floods. As this makes water availability less predictable for drinking water and agriculture, the creation of reservoirs may be advisable, both to reduce the impact of floods and as buffers for dry periods.

Today we have many reservoirs that were formed due to dams blocking the course of rivers, but something similar could be done for rainwater, not unlike historical cisterns that once used to be extensively used throughout the world, like the famous Basilica Cistern below the city of Istanbul. It’s perhaps ironic that many of such cisterns were abandoned over the years, even as the need for them becomes more apparent today.

Water technology = technology

Not dying of thirst?

Can recommend checking out the search results for “Tech In Plain Sight”, “Mining and Refining” and many of the indoor farming, plant automation projects / articles and other stuff that comes your way at the intersection between civilization and technology.

Dealing with water issues often bears all the hallmarks of a good hack: having to make do with limited in-situ resources, learning as you go, and experiencing varying degrees of failure.

You’re of course welcome to skip this article, but do try to appreciate the bigger picture the next time you happen by the usual prepper / survival life hack videos that teach folk how to make an emergency water filter with sand and charcoal.

A place for those with a strong sense of curiosity, but apparently you were in the wrong line when God was handing that out.

Access to potable water is the eternal challenge of humanity. Honestly, it underlines our fundamental weakness as a species but our water-rich environment makes it easy to forget that fact. I mean, it literally falls from the sky on this planet. Our water recycling technology is passible but if we are ever to seriously leave this oasis and live in various places among the stars then we will need to adapt our biology to be more resilient and water efficient.

“This healthy system did however begin to break down during the Late and Terminal Classic period, with the sediment record showing a gradual increase in contamination from cyanobacteria and human waste”

That’s an ongoing problem.

You build a really monumental piece of infrastructure, like Hoover Dam, everyone’s all “yay we’ve solved this basic problem for generations to come”, so they duly forget about that basic problem for generations to come, until one day it’s like “hey how come water isn’t coming out of the tap”. And now the problem is ten times bigger and more urgent than when it was solved the first time round.

I think big infrastructure is the right solution, but we need to figure out how to make it much more central in the long-term public consciousness. Like, maybe we should all be going to our local nuclear power plant / reservoir / garbage depot to make burnt offerings a few times a year, or something.

That’s called a “school trip”.

Well exactly. Visiting the sewage treatment plant in 6th grade was pretty big for me, and I reckon if we all did that at least once a year, we’d think right about infrastructure.

I’m from the Netherlands, where we have this constant fight with water. We had an English friend over and she was in awe about how much we knew about the water system. It came down to her having had geography in school for maybe 2 years, where I have had at least 3 or 4 (45mn) hours of geography for my entire school career from primary school up to the end of high school (12 years).

It’s not just a school trip, it’s continued education so we deeply understand the subject.

Heck, it’s even in politics, every 4 years we get to vote for our water management body (which is a separate layer of government from the municipal, provincial, national and EU levels)

Note the difference between the swamp Germans and the residents of New Orleans.

It’s because the economy of Amsterdam justifies and pays the expense.

Verses New Orleans, which expects the federal government to pay for everything. Including a 90% money diversion rate to the local war lords.

For example, before hurricane Katrina the federal government sent them some 100million dollars for flood control. They spent it on ‘bread and circus’, then complained after being flooded, still haven’t stopped complaining.

New Orleans in general should be _abandoned_. New New Orleans built someplace sane. French quarter sold to Disney.

Port is already adequately protected from floods, as it’s not a money sink.

https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/solved-mystery-spiraling-holes-nasca-region-peru-005704

great article, nicely written

Beer is what, 95% water. All of it potable. Problem solved.

Unless it contains heavy metals.

In Ancient Egypt the one source of water was the Nile, which was filthy. The soil washed down from the Ethiopian highlands that renewed the fertility of the fields was no doubt also full of bacteria. As a result everyone drank beer. Alcohol is toxic to humans in sufficient quantity, but it was more toxic to waterborne diseases.

Nope: It’s the boiling the wort step that kills the bugs.

However.

Yeah beer!

Boo bread, waste of grain.

Oh no snowflake big mad? I better go abort a baby so I can power my EV.

Nestlé has joined the chat

The word ‘potable’ comes from the ancient Mayan practice of suspending tubers (i.e., potatoes) in drinking water cisterns to impart a slightly basic pH level to the water. Unfortunateky, this practice led to the development of widespread cisternitus disease in the Mayan people and is often cited as a contributing factor to the demise of the Mayan civilization.

What do you mean by “cisternitus”? I can’t seem to find anything online about it.

You need to buff up your linguistics mate … ‘Potable’ from ‘potare’ Latin ‘to drink’

Potable – from the Latin potare – to drink

I live on a hilltop in a “stone” house and have a 3 megaliter “cistern” carved out of soft sandstone at the bottom of the hill. Coincidentally my wife is also of mesoamerica heritage. :-) We also have a water bore and rain collection tanks, technologies that required modern metalworking technologies. Imagine what the world would have been like if a lost Roman ship had made it all the way to Central America with the knowledge the Romans had! Not to mention if they had made it back with the Maya knowledge of mathematics.

And nowadays you can get tiny, lightweight filters under $20 that can be flushed and reused up to a rating of 100,000 gallons – though that’s just for individuals, not societal water, and even then it doesn’t filter out various dissolved things.

Oh and for what it’s worth, if you’re surrounded by unpopulated areas, waterways are your trade route because you can’t carry enough food in a cart to move that cart more than a certain distance, nor can you assume forage will be enough. It was easier to ship things down to the ocean and back up another river than to go overland, in general. So while water for drinking was important, and the cities had plenty of reason to figure out how to do it given that contamination flows downstream, actually using it for trade is very relevant too. The apparent ability of nomads to exceed the range limit and do many things without infrastructure can be explained by remembering that they still traded for the things they couldn’t make and that they had much more effective foraging because they didn’t just have a man in a cart. By moving with large numbers of grazing animals, you can have them consume grass and turn it into food a lot faster. And they moved around so much not because nomads were some whimsical savage wanderers but because if that’s your strategy, you have to keep moving the herd to fresh grass in order to feed all those animals, so you have to have a territory to circle around over a period of time, and if someone tries to move in while you’re letting it regrow then you have to fight them off because they’re threatening your food supply. And also your supply of things to drink, if you rely on your animals to provide milk or blood when you’re in a pinch. And of course there’s plenty of water rights problems, whether for ranching, farming, drinking/bathing, etc. It’s an interesting topic.

Apparently one can combine trash and flowering plants to create a floating constructed wetland. More on Wired: https://www.wired.com/story/planet-pioneers-nagdaha-small-earth-nepal-soni-pradhanang-ftws-floating-treatment-wetland-systems-water-cleaning-pollution/

The article says it’s being done in north America.

‘Urban waterways like Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, Boston’s Charles River, and the Chicago River have all successfully deployed FTWS to clean their waters.’

Living clumps of vetiver grass can be used to clean bodies of water. The plants are attached to some sort of floating object and allowed to grow. The long roots extend into the water.

Please see https://youtu.be/Wzu_tju31Hs for a demonstration.

No mention of Hg phytoremediation potential, but vetiver seems to be not-so-great at sequestering Pb [1]. But here’s where it gets weird – “Mercury-resistant bacteria including Pseudomonas, Proteus, Enterobacteriaceae, Alteromonas, Aeromonas, and Xanthomonas are used for mercury bioremediation.” [2]

[1] https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=113321

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780323904520000050

Surely an important part of maintaining access to fresh and potable water is preventing known contaminants from entering the supply and watersheds.

Vetiver grass plantings have been used to manage/rehabilitate contaminated and polluted soil. This can be found at the site of landfills/garbage dumps and metal and coalmines. This document gives some details https://www.vetiver.org/PRVN_mine-rehab_bul.pdf as does https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRWFBB-ocRs